I meet 14-year-old Fatima at the Essex hotel she’s been staying in for seven months since she fled Afghanistan.

She tells me how much she appreciates being able to attend school each day. She knows that under the Taliban, girls are not allowed to attend school. Parks, gyms and swimming pools are also off limits.

But her new life in Colchester has its own problems. Her hotel food is “mainly rice and beans” and there’s little space for her parents and five siblings.

It’s Eid when I meet the refugee Afghan mums and children at a celebration they’re holding in a small grassy area behind their hotel.

Back in Afghanistan, the mothers would have spent much of the day cooking. But Fatima’s mother, Fakhriah, tells me she feels she “has no purpose” as they are forbidden from cooking their own food at the hotel.

English lessons are held two days a week. One mother keeps nervously scratching her hands, and I’m told her extended family members were recently killed by the Taliban.

Fatima is also scared as her family is being moved again next month to more permanent accommodation. It will likely mean starting again at a new school.

She has settled into school life in Colchester and has made friends. But her life is soon to be uprooted again.

A months-long investigation by Schools Week has found she is one of thousands in this situation. We uncover how poorly co-ordinated and last-minute placements by the Home Office leave schools scrambling to accommodate dozens of traumatised children, who can then disappear without warning, leaving schools with big funding shortfalls.

The “chaotic” movement of families around the country is also disrupting children’s education, while they are left for months in unsuitable hotels without decent food and allegedly at risk of abuse.

Sebastian Chapleau, assistant director of Citizens UK, says: “The fallout from the government’s hostile immigration policies is piling misery on to children who’ve already been through severe trauma getting to the UK.

“It is schools that are being left to pick up the pieces, but without the access funding for the additional language and emotional support these children so desperately need.”

Children left in limbo

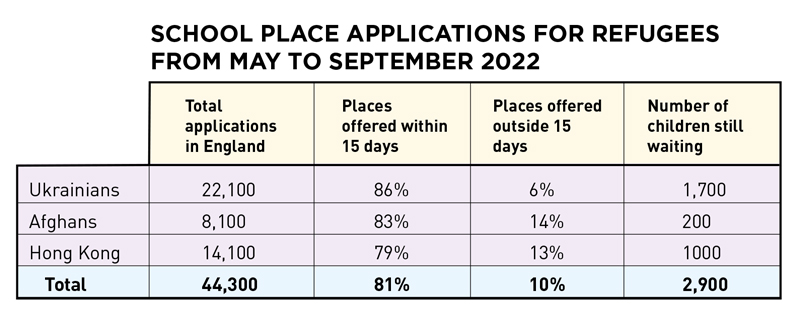

Between May and September 2022, 44,300 school applications were made for refugee children arriving via official routes – half from Ukraine, a third from Hong Kong and the rest from Afghanistan.

Councils are expected to find school places within 15 days, but in 4,000 instances they took longer. Almost 3,000 children (7 per cent) were left with no place by September, according to the latest Department for Education data.

But even when children do secure school places, they can be taken away with little notice.

Most Afghan refugees were put up in hotels, with the expectation they’d soon be moved to more permanent accommodation.

There are currently around 8,000 Afghan families housed at 59 temporary hotels across the country.

The government “strongly recommends” that they start looking for new schools before moving. But many still have no idea where they will end up.

Fakhriah has been told she has to leave the Colchester hotel by August 8. “[The council] told us there’s no place for you in Colchester. It’s not known where we will be housed, or the fate of my children’s education.”

Local Government Association adviser Louise Smith says it can be difficult to find suitable and affordable housing, particularly for Afghan families, who tend to be large. “But the stability of school is so important.”

Daniel Rourke, a lawyer from the Public Law Project charity that works on behalf of families in such situations, says “chaotic moves” have “already prevented some children from taking exams, and many of those same children are now facing the threat of homelessness”.

Since fleeing Sudan in 2020, 16-year-old Ann Bashir and her family have been moved four times and are expecting to be moved again from their Hove flat. Each time, they’re given half an hour’s notice to gather belongings.

Last year, they were moved to detention accommodation in Tower Hamlets, east London, leaving Ann with a five-hour daily commute to her school, Cardinal Newman in Brighton.

In April, while she was revising for her GCSEs, they were moved again into a rundown Brighton hotel.

Despite the end of the month deadline to move Afghan families, Simon Ridley, the Home Office’s second permanent secretary, told Schools Week on Tuesday “a lot of them as of today don’t have housing yet”.

“Afghan families…can’t possibly live forever in a hotel. So we’ve got to start progressing this.

“Some families will stay local, for sure…Some might move further away. But…families move around the country.”

Schools have ‘little time to prepare’

Sackville School in West Sussex was given “little or no time to prepare” for the arrival of about 20 refugee and asylum-seeking pupils last spring, says headteacher Jo Meloni. The 1,700 pupil school was already at capacity.

While the school “welcomed them with open arms”, she questions why the mainly Afghan and Ukrainian children aren’t more evenly spread across other areas.

The Home Office decides where to move families, but once they are moved the council then has a responsibility to secure school places.

Kent Council questioned the Home Office’s “wider decision-making” during the emergency evacuation from Kabul in August 2021.

While families were “waiting on the runway”, Home Office officials were contacting Kent staff to ask about the availability of school places “so their take-off could be authorised”, a report to the Schools Adjudicator said.

The Home Office also last year continued placing families in Ashford and Canterbury, despite being warned by Kent and the DfE about “lack of school spaces”.

All year 9 places in Canterbury were filled, resulting in pupils being allocated to schools “at the extent of reasonable journey times” and adding “pressures on [Kent’s] already struggling [school] transport network”.

Asylum-seeking and refugee children often take priority in admissions – including, for instance, over sibling places – which can cause frictions.

Herefordshire says a 20 per cent rise in in-year admissions in 2021-22, “mainly from out of county and abroad”, was “putting strain on our city schools… largely at capacity already”.

In Kingston, southwest London, a large rise in in-year applications, 45 per cent from overseas, is adding to a “scarcity” of places in some year groups.

Phil Haigh, chair of governors at Cherry Lane Primary, which is near three asylum hotels in Hillingdon, west London, is seeking to change the admissions criteria at his school to give priority to siblings. Some families pulled their child out when a sibling didn’t gain a place.

About 50 of its 600 pupils are currently asylum-seeking children.

Welcoming schools left out of pocket

Schools receiving asylum-seeking children – those arriving in small boats – are left out of pocket, too.

Schools are only funded for pupils registered with them the following census day, and only then from the start of the next financial year which is April for multi-academy trusts and September for maintained schools.

But these families have normally been moved on by the Home Office by that point.

Almost 700 asylum applications were made for accompanied children in the 12 months up to May, and 5,000 for unaccompanied children, according to Home Office data.

Council areas with airports and ports have seen a greater influx. But councils across London recently joined forces on an asylum dispersal plan to “hold the Home Office to account” in ensuring families are spread more evenly between them.

Hounslow, home to eight asylum hotels, processed more than 1,800 overseas in-year school applications last academic year.

The support for “trauma, language, clothing [and] meals” places “huge pressure on resources – not just financial”, a report from the area’s school forum says.

But Haigh says “very few” children stay as long as a year, “most a matter of weeks” and some “never turn up” after enrolment. Their places cannot be refilled as the school is unable to trace them.

“We’re stuffed by the Home Office,” he says. “We get no correspondence from them at all. There’s no reason why, if they had their bloody act together, they couldn’t communicate where the child is moving to.

“We’ve had parents turn up at lunchtime to pick up children to go somewhere else [to live], but they don’t yet know where.”

William Byrd Academy, a 550-pupil school run by Middlesex Learning Partnership, has hosted 64 asylum-seeking children since September 2020.

The school ‘requires improvement’, but is tracking towards good. Trust chief executive Tracy Hemming says it tried to use the school’s “fragilities” as “mitigation” for emergency funding, but to no avail.

Its budget surplus to March 2023 dropped from £318,304 to £145,638.

The school’s local authority, Hillingdon, is urging the Home Office for a “fair level of funding” to cover costs for schools with asylum-seeking children.

In Essex, the council stumped up £1 million contingency within its growth fund for schools admitting a significant number of asylum and refugee children, with £355,000 so far allocated.

Councils receive funding for Afghans of £20 per pupil per day, but this is lagged by a term despite “large volumes” arriving.

One of its schools, St Andrews primary – near Fatima’s hotel – had to accommodate 37 Afghan children at once.

“We would expect schools to take two to three children but when the numbers come up, we need to appoint staff from day one and [face] additional costs,” Essex council said.

Children failed by broken systems

The complex needs of these children – who have often been through significant trauma – are also butting up against support systems already under strain.

Haigh claims some of the Afghan children at his school lie down in the playground thinking that a firefight is going on above their heads.

“It was possibly PTSD, we don’t know as they can’t get a diagnosis because CAMHS is overwhelmed.”

Kingston Council highlighted an “increasing number of children…from overseas” with “highly complex needs”, “likely to need specialist provision, but requiring an [EHCP] assessment”.

But almost half of children nationally waited beyond the legal deadline for a plan last year.

“Schools are concerned whether they have the appropriate resources to support the child, which makes the final allocation difficult,” the borough said.

Hillingdon’s schools forum adds that “when a class has a significant proportion of children with EAL/trauma with no extra support, the other pupils also suffer”.

The placement of asylum seekers in hotels has also sparked community tensions in Lincolnshire, Brighton and Knowsley, with a protest in Knowsley in February leading to 15 arrests.

Meloni says the children have added a “cultural dimension” to her school that it is “benefiting from”, being in a “predominantly white, middle-class” area.

“The majority are thriving to an extent, because they’re happy to be here.”

But the timing of the bus returning pupils to their hotel means they cannot stay for extra-curricular activities, and makes it difficult for school staff to “form relationships with families”.

Hunger, abuse and disappearance

Ann finally broke down to the school’s pastoral leader Georgia Neale about her family’s living situation.

She had been filling up on free school meals and taking school cafeteria leftovers back to her family.

Four days into the family’s stay, Neale visited the hotel – despite visitors not being permitted – to ask staff why they had not been fed.

“At first, they denied the family were staying there.”

Then they were finally shown where the washing machine and cafeteria was, although Neale describes the pre-packaged “aeroplane” food as unappetising.

But Ann was “so scared if they complained they’d get sent back to Tower Hamlets”.

Citizen’s UK’s Froilan Legaspi claims some asylum hotels are serving “undercooked chicken and expired milk”.

“Many children are losing weight”, partly because a policy change during Covid allowing children with no access to public funds free school meals is being “applied inconsistently”.

There have been reports too of violence and sexual assault against children in hotels.

And as of January, 440 unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (separated from their parents or carers) had gone missing. By June, 154 were still unaccounted for.

Haigh says accompanied children are also disappearing. Albanian children living in hotels with their mothers in some cases “just disappear… Their fathers … pull up at the school gates and whisk them off, nobody knows where.”

There were 5,570 unaccompanied asylum-seeking children in 2021-22, up from 2,230 in 2012.

Many are in temporary hotels until councils can find them more secure placements. But as of January, more than 4,600 had been in hotels since July 2021. For many their only education is provided by hotel support workers.

A government inspection of such hotels last year found activities limited to art, some sport and “some basic, perfunctory informal English language sessions”.

“By failing to provide any formal education or schooling, young people’s basic educational needs were unmet,” it said.

Schools go above and beyond

Despite the myriad of problems and hostile government environment, schools are making children feel welcome.

At Sackville, families have been invited to its summer school; every pupil has been given a “student buddy”.

Dozens of sixth-formers have been trained in TEFL (teaching English as a foreign language) qualifications to support youngsters and the school paid to train two teaching assistants in EAL (English as an additional language). “We’re doing what we can,” Meloni says.

William Byrd is providing clothing, English lessons and coffee drop-ins for families.

Cardinal Newman has supported Ann to find witnesses for her asylum case, lodging “mitigating circumstances” with GCSE exam boards over the stress she is under and paying for her to attend the school prom.

“The support I‘ve received from everyone in school made me feel welcomed and loved,” she says.

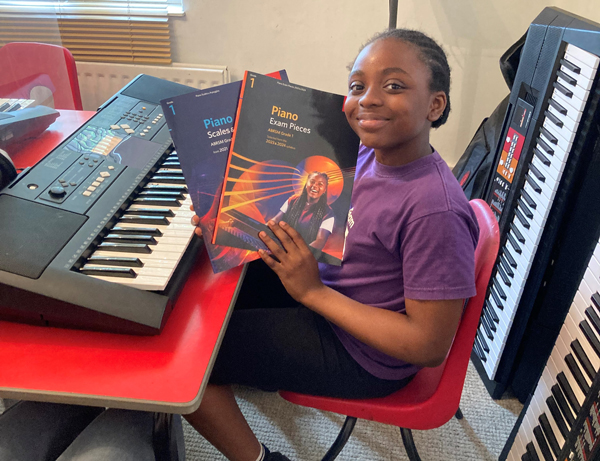

At Surrey Square Primary in south London, children get a free weekly extra-curricular club or music lesson, costing £1,100 a term.

“Otherwise they really miss out and it’s not an equal playing field,” says Fiona Carrick-Davies, the school’s family and community co-ordinator. It also supports families with a food bank and furniture.

Of its 460 pupils, 24 have no resource to public funds because of their immigration status, although some families have lived here for decades.

Grace Adedeji, a carer from Nigeria who arrived nine months ago and whose two daughters, 10 and 8, attend drama club, says: “Life is so difficult. But I really appreciate the help we get from the school.”

Your thoughts