Just 155 schools are likely to be affected by a plan to move long-term underperforming schools into multi-academy trusts.

Ministers this week reaffirmed their commitment to consult on moving schools with successive ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’ ratings into “strong” trusts. The policy will be focused on the Department for Education’s new “education investment areas”.

However, analysis published this week shows just 155 affected schools are not currently in trusts (0.7 per cent).

The plan to move underperforming schools was announced last year. The DfE initially said it aimed to target schools with three successive grades that were less than ‘good’.

But this week’s levelling-up white paper refers only to schools with successive negative ratings. The DfE said its plans would be subject to consultation in the “coming weeks”.

However, even if the policy applies to those with two negative ratings in a row, a low number of schools will be affected, according to analysis by Education Datalab.

Just 1,215 schools of about 22,000 nationally have been rated less than ‘good’ in their two most recent inspections. Of those, only 612 are in education investment areas, where this policy is due to be implemented.

However, most of those schools are already in multi-academy trusts. Just 135 are currently not in any trust, while a further 20 are standalone academies.

Move will affect ‘small number’ of schools

Researchers Natasha Plaister and Dave Thomson said the measure was “only likely to affect a small number of schools”.

There are also no details on how “strong” trusts will be identified. A discussion paper by the Confederation of School Trusts this week described them as having expert governance, focusing on quality of education, being efficient with workforce resilience and wellbeing.

The proposal by the government has been likened to the 2015 “coasting” schools policy, which was ditched in favour of a lighter-touch school improvement offer.

Paul Whiteman, from the National Association of Head Teachers, said the government “appears to have once again reached for simplistic solutions linked to structures and targets. Pointing at the problem is not the same as solving it.”

But Nadhim Zahawi, the education secretary, said the plans in the white paper would help to create a level playing field and boost the economy, locally and nationally.

The government said education was at the “heart” of its levelling up reforms to give “every child and adult the skills they need to fulfil their potential, no matter where they live”.

Poorer pupils lose out under ‘investment areas’ plan

Most disadvantaged pupils and those falling behind at school won’t benefit from support under the government’s new “education investment areas”.

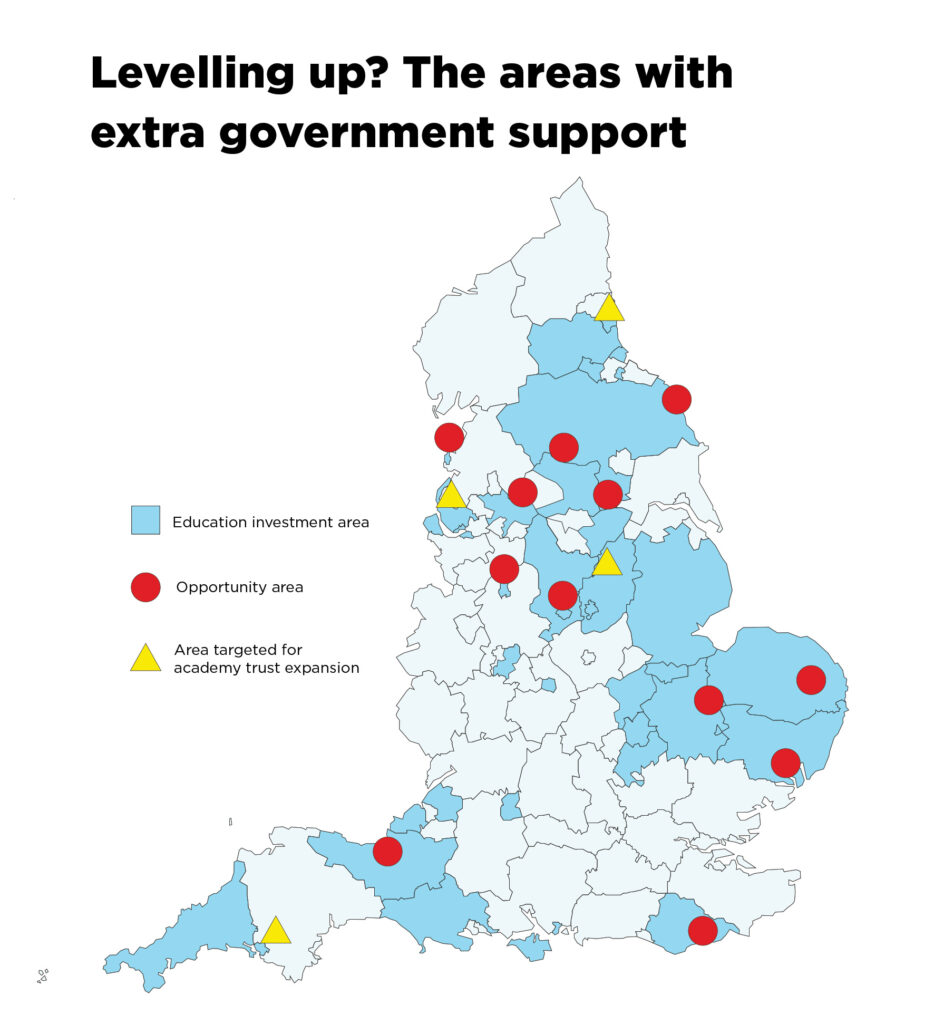

Teacher retention payments, academy trust expansion and new 16 to 19 free schools will be targeted at the 55 areas under plans set out in the “levelling-up” white paper.

The Department for Education said the areas were selected based on outcomes at key stages 2 and 4. But no new funding has been announced to back the policy.

EIAs, which cover about a third of council areas, account for 39 per cent of pupils eligible for free school meals nationally and 38 per cent of those not meeting the expected standard at the end of primary school.

Some of the most deprived areas in England are excluded, including Birmingham, Hull and the London boroughs of Barking and Dagenham and Hackney.

Dr Sam Baars, the deputy chief executive of the Centre for Education and Youth, said the new EIAs were a “badly targeted, inefficient bit of area-based policymaking”.

He said most disadvantaged pupils and those who did not do well at the end of key stages 2 and 4 “don’t go to school” in the areas and “won’t benefit from this policy”.

Leaders warn of ‘unintended consequences’

Geoff Barton, the general secretary of the ASCL school leadership union, also warned about “unintended consequences”.

“Obviously, if you improve pay in some geographical areas, but not in others, there is a danger of drawing teachers away from areas that do not qualify for extra support.”

Natalie Perera, the chief executive of the Education Policy Institute, said it was “crucial” that poverty in London was not overlooked.

The announcement has also prompted speculation that the areas are being set up as a successor to the DfE’s flagship opportunity areas policy..

The 12 opportunity areas, now in their fifth year, have received £90 million in funding for school improvement, and teacher recruitment and retention.

But Sir Alan Wood, a former council official who has led several government reviews into children’s services, said the new policy had the “same flaws” as previous education action zones and education improvement areas. He cited issues such as “top-down imposition, modest additional resources, a failure to attract additional teachers and an obsession with targets”.

Your thoughts