Raksha Pattni, national partnerships director at Ambition Institute, tells Jess Staufenberg why new CPD partnerships with councils will be a game-changer for schools

Raksha Pattni, who oversees partnerships at teacher development charity Ambition Institute, is someone who deeply understands the impact of place and geography on one’s life chances. Her family are from India, she was born in Tanzania and her nationality is British. As with her own life, place has played a big part in her professional work.

At Ambition, she was director of the north for almost four years – focusing on helping teachers tackle north-south disadvantage gaps.

Now in a national role, Pattni is driving forward “place-based” partnerships – providing training for lots of schools in one area who then learn from each other too. In January, she signed up Liverpool City Council and 80 of Liverpool’s schools to Ambition’s CPD programmes over the next three years.

“Currently we just work anywhere with individual schools, but I want us to work with multiple layers of teachers over a sustained time in one location,” she explains. “With individual schools you still get that impact, but it’s just so intensified this way.”

Signing up so many schools in one city is a big win for Ambition. Liverpool City Council will pay £754,000 from its own budget so that both maintained schools and some academies access Ambition programmes for free. It is the first such partnership in the country, the pair say.

Participating schools are in groups of nine, with three senior leaders and three middle leaders selected to access Ambition’s Transforming Teaching programme from each school. It’s a one-year training course that “tackles entrenched underperformance in the classroom and improves the quality of teaching and school leadership”, explains Pattni. All 27 senior leaders in one group of schools work together, and the same for the 27 middle leaders. In total, 400 educators will be reached.

“[CPD] is so impactful when you bring big groups of people together,” smiles Pattni. “There’s a real momentum that builds – it has a multiplier effect.”

The schools volunteered themselves for involvement. About ten teachers on the Transforming Teaching programme will also be selected for Ambition’s two-year ‘teacher education fellow’ programme on delivering effective CPD, which the ‘fellow’ then spearheads back in their own school. Last of all, 25 staff will be selected for Ambition’s two-year ‘future heads’ programme on preparing for headship.

“You don’t want schools working in isolation,” nods Pattni. “For me, this is about creating that ecosystem of support at a place level.”

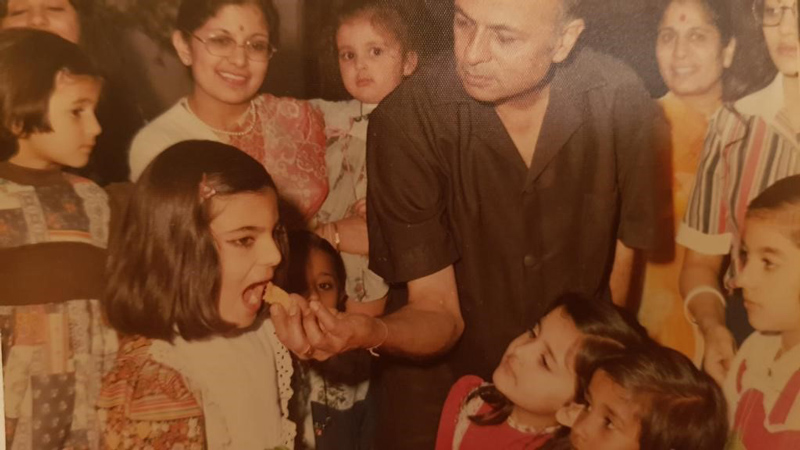

Pattni has an impressive professional history of creating opportunity in local areas. It may be a quality she inherited from her grandparents and parents, who both made big global moves to improve their families’ chances.

Her ancestors were jewellers and goldsmiths in Gujarat, but her grandfather left aged just 18 for Tabora, a district in Tanzania, to be close to the area’s goldmines. Her father was one of 14 children, and later he and her mother had seven daughters. As the youngest, Pattni felt “very loved” by a big family.

Pattni’s parents also drummed a social conscience into their daughters. “They were very philanthropic, giving food and clothes to local orphanages, and buying books or paying for the cost of teacher training for schools.”

School here was very different to the British schools she’d attend later. “There would be about 50 to 60 children in a class, and our school day would start with cleaning the school. All the children had jobs in the morning, cleaning the yard or the staffroom, or, if you were really unlucky, you were selected to clean the toilets – every child’s worst nightmare!”

Pupils arrived in school “with their school bag and cleaning kit”, she continues. It was a happy environment, and together she and her Asian and African friends would share chapatis and mangoes at lunchtime.

But a war between Tanzania and Uganda brought a terrible incident into her young life. Crime and civil unrest were increasing, and one night, intruders broke into the house.

“All I remember is a massive noise… I think they’d got a massive rock to fling the doors open. The lights had been cut and it was dark, and one of the gang had a machete or a knife and they were pushing it into my dad and he was trying to hold them off.”

At just 11 years old, Pattni saw her father’s hands stripped into ribbons from the fight. He needed six hours of surgery. The young Pattni struggled to sleep for months.

Her parents rapidly packed her on to a military plane bound for Britain with her grandmother. She stayed with an aunt and uncle in Leicester, now attending a small fee-paying girls school, Fosse High School.

“I must admit, I did struggle,” Pattni says. “I didn’t feel included, because I looked different, my accent was different, I wasn’t up to speed with fashion and I didn’t understand the slang.”

Afterwards came Gateway Sixth Form College in Leicester, followed by Coventry University where Pattni studied economics. Aged 23, she got a job at a charity called Belgrave Baheno (baheno means ‘sisters’ in Gujarati), which supported women into better-paid jobs and education. There she set up a partnership with Leicester’s Marks & Spencer to recruit more women from ethnic minority backgrounds: “I’m still very proud of that.”

Building local partnerships became Pattni’s specialism. She became head of race equality at Preston City Council, where she set up the town’s first ‘mela’, a big South Asian fair with food, rides and games, bringing everyone from all backgrounds together.

Her work soon caught the eye of the charity Business in the Community, which strengthens links between business, public and voluntary sectors. She became area manager for Lancashire, then regional director for the north-west, and finally, area director covering the north-west, the west Midlands and the south-west. Her legacy was a programme called Business Class, where a school is needs-assessed for how a local business can help, such as in HR or marketing.

“In 20 minutes my CEO had signed off £50,000 to go away and pilot the programme!” she beams. Six months later, she secured a quarter of a million pounds in government funding. It became Business in the Community’s flagship national programme, expanding to 500 schools with 300 businesses.

Then in 2017, Pattni joined Ambition as director of the north.

Her focus was helping staff tackle the pupil attainment gap with the south. The statistics in her first year were eye opening: in 2018, only 16.4 per cent of students in the north-east received grades 7-9 at GCSE, compared to 25.7 per cent in London and 20.8 per cent nationwide. Around the same time, northern secondary schools were receiving £1,300 less per pupil than secondary schools in London, until a funding formula change in 2018.

So Pattni joined the government-funded Northern Powerhouse Partnership on its education and skills committee, contributing to its ‘Educating the North’ report. (This included a commitment from businesses to provide career support to 900,000 northern pupils, which sounds straight out of the Pattni playbook.)

Her team at Ambition also “fed back to the government that tutoring is really what was needed in the north,” which she says helped prompt the national tutoring programme.

Then in 2020 Pattni took on her national role, tasked with bringing Ambition’s programmes to as many schools as possible (Ambition now works with 28,000 participants: that’s one in 16 teachers, or the equivalent of working in one in four schools.)

These programmes include government-funded contracts – the early career teacher programme and national professional qualifications – as well as Ambition’s own: the trust leaders programme, transforming teaching, curriculum for senior leaders, masters in expert teaching and teacher education fellows.

But last month Ambition lost out, in a high-profile blow, on the government’s £121 million contract for the Institute of Teaching, to a group including Harris Federation and Star Academies. The charity dropped legal action after agreeing a confidential damages settlement with the government.

Unsurprisingly, Pattni says she cannot discuss this. Instead, she is jubilant about the “place-based” drive.

Where next? I ask. There is a similar pilot running with Middlesbrough council with seven schools, and Pattni is looking at Leeds, west Yorkshire and Blackpool.

From Tanzania to Tyneside, Pattni has watched and learned from the places she’s lived.

Even as the government’s rhetoric has shifted from the place-based ‘Northern Powerhouse’ to the more national ‘levelling up’, it looks like Pattni will keep the importance of the local in the spotlight.

Your thoughts