Susan Douglas, part-time chief executive at The Eden Academy Trust, tells Jess Staufenberg what visiting 63 countries with the British Council brings to her own special educational needs academies

One of the best lessons Susan Douglas has ever seen was in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. It was a lesson on rhythm, being delivered by a single teacher to 100 students.

“You know when a teacher just has the room? The children were hanging on to her every movement,” begins Douglas, chief executive at The Eden Academy Trust.

“She had no resources, no instruments. She had nothing but her presence. They were completely engaged.”

Unusually for a CEO, Douglas is part-time, working three days a week at her trust overseeing six special needs schools across London, Northumberland and Cumbria.

The other two days she is a senior schools adviser to the British Council, and has visited no fewer than 63 countries. She tells me about some of the most extraordinary things she has seen in other systems.

Singapore excelled around continuous professional development, she says. Teachers there can choose one of three career tracks: headteacher, subject specialist or master teacher.

Being a subject specialist is so highly respected in Singapore that “at the highest rank, you can earn as much as a head”, says Douglas. It’s a completely different approach to England, where “we remove our best teachers from the classroom to go up the career ladder”.

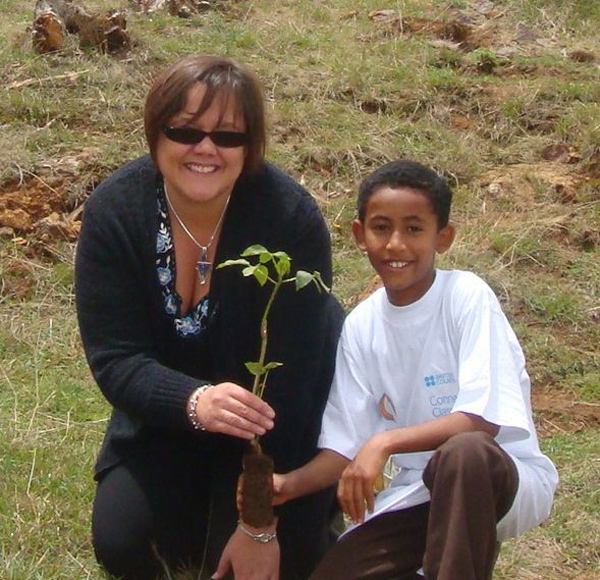

Another school that stuck was a highly inclusive one in South Africa. The headteacher had deliberately recruited the entire staff body to reflect the very diverse pupil cohort of the school: across ethnicity, gender and special educational needs.

There was also no separate special educational needs “unit” in the mainstream school and, instead, a commitment to all students learning together, with extra support where needed.

Finally, at a school in Brazil, Douglas saw great practice around community-school ties. For example, pupils had gone out into the local area and found water pollution was a serious problem, so organised community events, campaigns and speeches with local families to improve the water purity. “Really intentional community engagement was completely embedded in the curriculum there,” says Douglas.

It’s all possible through the British Council programme she leads, called Connecting Classrooms, and the joint British Council and Department for Education programme with Singapore called Building Educational Bridges. She has taken 120 UK headteachers away and brought staff back too.

But it’s not about poaching ideas, Douglas explains. It’s about reconsidering your own system.

“Every year when we go to Singapore, UK teachers will often say they can’t wait to go out there. But at the end, they often say the most important bit was actually trying to explain our system to them.

“Seeing your own system through someone else’s eyes is very powerful…

Seeing your own system through someone else’s eyes is very powerful

“I think that in schools, things very quickly become historical, because we’ve always done it that way.”

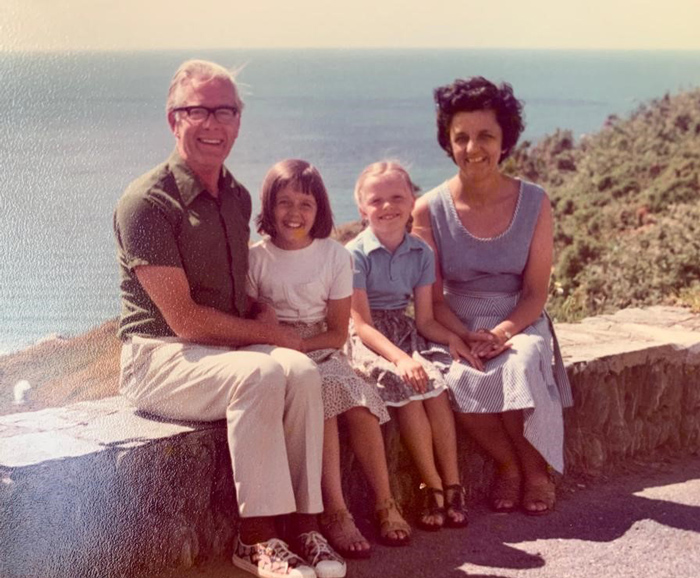

Clearly driving Douglas is the pursuit of high expectations in the most ambitious sense. It was something she absorbed from home – her father, a financial adviser, and her mother, a nurse, would write questions on a blackboard in the kitchen for her and her sister to work out.

As a child, Douglas announced she would “be a headteacher by the age of 30”. She beat her goal, landing her first headship aged just 28.

“My headteacher came in one day and said, ‘I’m just popping out for a minute’,” Douglas explains. “But she never came back.” So the young Douglas was unexpectedly in charge.

In some ways, she had a very clear idea of the kind of headteacher she didn’t want to be. For instance, while in her mid-20s she rang to excuse herself from work because her father had died and was unsympathetically told: “But it’s parents’ evening”.

However, in other ways, she was unsure. “So I thought, what I’ll do is I’ll follow all the rules. The school’s bound to get better, and it did. It went from being a not particularly good school, to being quite a good school. But that’s as far as I could take it, really.”

I think that in schools, things very quickly become historical

Then in 2005 the British Council offered Douglas a study tour placement to Thailand.

“It was life changing. So, I came back and we started to do some much more creative things. We lost that ‘we’ll follow all the rules’ approach!” The school landed Ofsted’s top grade.

So for two decades now, Douglas has always held two jobs (from 2007 she also worked for the National College for Teaching and Leadership).

So how does she fit her job into three days – and could more small trusts follow suit?

“My team know they can ring me any day if needed,” explains Douglas – but otherwise her strong top team, including a chief operations officer, director of central services and schools, and director of academy development, hold the fort.

She says she doesn’t know why it’s not more common in small trusts, adding, “Flexibility is more important than ever since the pandemic”.

Her varied experiences have made Douglas an ambitious and creative leader, it seems. But her high expectations are not often matched by the government, she says. Instead, the SEND sector is too often treated as an ‘add-on’.

This ‘afterthought’ attitude explains why she was the only leader of a SEND academy trust on the DfE’s Covid-recovery group, out of 12 members, she says.

“The fact we have a schools white paper that will probably get through in the life of this parliament, focused on the majority of children, and then we have a SEND green paper, which was already delayed…

“Will it get kicked into the long grass? My worry is that often, it’s ‘something we’ll sort out later’.”

There are some good structural proposals in the SEND green paper, Douglas continues, such as the promise to set up a new national system of funding (in her trust, the biggest difference in top-up funding for a pupil with similar needs across two local authorities is a staggering £8,488 per year).

But it seems some of the biggest challenges she faces are not addressed.

“I’m desperate for teachers, but also teaching assistants. And therapists are like gold dust,” says Douglas. “So I don’t understand why, when the government is setting up incentives for certain shortage subjects in secondary, special school teachers aren’t one of those.”

It’s undeniable logic: the special needs schools sector has up to double the number of teacher vacancies as the mainstream sector, government data shows.

But the problems in the green paper go even deeper, she continues.

“Society still adopts a medical model approach to children with special educational needs: what’s wrong with them, and how can we make sure they will fit with the rest.”

It’s this underlying principle that means low expectations of SEND pupils persists, says Douglas.

Again, other countries have shown the way. She recalls visiting Ontario, in Canada, in 2017, where mainstream teachers were encouraged to study a SEND qualification, resulting in better pay.

“It was about incentivising teachers to see themselves as teachers of SEND. The principle there is one of high expectations around expert teaching.”

By contrast, Douglas says a teacher in her trust with a first-class degree was advised by their Russell Group university that going into special education might be a “waste”.

It’s clear Douglas is very grateful for her three-days-a-week CEO role. (The cost saving has partially contributed towards the trust being able to pay for central therapy and services for its families, including employing 28 therapists.)

But the other major benefit is “being able to bring back all the learning I do in my other job into the trust,” says Douglas. There’s also a danger with special schools of “becoming isolated”, which all her external work mitigates.

This internationalist, innovative approach seems to be the opposite of the “medical model” approach to children with SEND that she criticises.

“It’s so important that people look outwards, whether it’s Birmingham, Northern Ireland, or Kenya,” says Douglas firmly. “We are so busy in education, it’s too easy to look inwards.”

To those truly dedicated to high expectations of all pupils, a visit to The Eden Academy Trust might be a good place to start.

Your thoughts