The woeful state of private alternative providers can be revealed for the first time, as a new analysis reveals almost one in three are not rated ‘good’ or better by Ofsted.

Only 71 per cent of private alternative providers, which are independently-funded settings that take in vulnerable pupils, currently hold one of Ofsted’s top two ratings. This compares poorly with state-funded pupil referral units, of which 89 per cent are ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’.

The findings, from joint research by FFT Education Datalab and The Difference, are the first of their kind, because the Department for Education does not separate data on private AP from mainstream private schools, making analysis lengthy and difficult.

Most alternative provision, which local authorities and schools commission for temporarily or permanently excluded pupils and those who may need specialist support, refers to state-funded pupil referral units, AP academies and free schools. However, a growing proportion is private.

The new analysis builds on Schools Week‘s investigation which last year revealed the millions of pounds multi-academy trusts have spent on private AP.

More recently, ministers have told the education select committee that Ofsted will increasingly examine how schools choose AP, as part of its inquiry into the sector.

The irregular geographical spread of private alternative providers is also laid bare in the new research, as is the huge increase in the number opening each year. Schools Week has the key findings:

1. Private providers get worse Ofsted grades than state PRUs

There are 117 private alternative providers currently open, of which 110 are under Ofsted’s remit and the rest are under the Independent Schools Inspectorate.

Of the 97 already inspected by Ofsted, only 71 per cent are ‘good’ or better – compared with 89 per cent of the more than 300 pupil referral units across the country.

Just nine per cent of private alternative providers are ‘outstanding’, half the proportion of PRUs. Sixty-two per cent are ‘good’, against 71 per cent of PRUs, while almost a fifth are ‘requires improvement’, compared with just nine per cent of PRUs.

Finally, nine per cent of private providers are ‘inadequate’, against three per cent of PRUs.

Kiran Gill (pictured), the founder of The Difference, a charity which runs alternative provision teacher training, said it was “very concerning that some of the most vulnerable learners are getting less quality, and it’s also concerning this is the first time we’ve found this out”.

“They need the highest quality of all,” she said, as many private providers continue to offer impressive support for vulnerable pupils and should be recognised for their work.

Thirteen providers have opened in the last three years and are awaiting an inspection. Of the seven inspected by the ISI, two had full inspections and both were positive.

2. The private alternative sector is growing

The number of private AP settings has shot up in the last three years, with almost 40 per cent of all providers that opened in the last couple of decades doing so since 2015.

In the nine years after the millennium, just 28 providers opened. But from 2010 to 2014, 47 opened and in the two years after that, a further 51 opened.

There have bee n 129 private alternative providers over that time, but only 117 are open today.

n 129 private alternative providers over that time, but only 117 are open today.

Philip Nye (pictured), from FFT Education Datalab, has the impression that “this is a sector with a lot of churn” with schools that frequently open and shut.

“We wonder whether these are small establishments run by just a few people, and when one person moves on the whole thing closes,” he said.

More private providers might be springing up as local pupil referral units either close or run out of space due to budget cuts and increasing levels of exclusions from mainstream schools.

3. The 3,000 pupils in private AP must be properly tracked

In total, there were 2,772 pupils on roll at the 113 private alternative providers for which there was data.

Of those, two thirds are boys, with just 920 girls in the system.

The researchers want the DfE to separate its data on private schools so the outcomes for pupils in private alternative provision can be tracked.

“Until this point, we’ve not had a proper dataset so we can look at the quality of the sector,” said Gill. The DfE needs to develop a database of private and state-run AP so schools can consider their quality before sending pupils.

The DfE already records private special schools as a distinct category to all special schools, so it must be possible to treat private alternative provision as a distinct category too, they added.

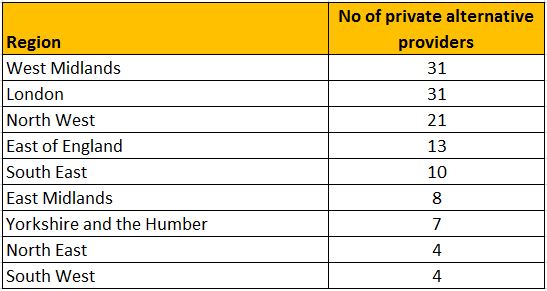

4. The amount of private AP differs wildly across regions

The number of private alternative providers varies across the country. For instance, there are just four providers in the north-east, but 21 in the north-west.

The west Midlands is the only region in the country to have as many private alternative providers as London.

In their blog, the researchers note that Birmingham in particular has a much higher number of private providers than other cities, with 16 in total.

That figure “dwarfs” the number in the local authority with the next highest number, which is Manchester with six providers.

Schools Week has previously reported on how the quality of alternative provision varies wildly across the country, with some councils offering only ‘inadequate’ placements and nothing else.

5. But this isn’t the whole picture

The data has been gathered because those private alternative providers are all registered with the DfE, but there is an unknown number of private alternative providers which are not registered.

Last month, the government abandoned a years-old proposal to force out-of-school settings to register with councils following a fierce backlash from faith leaders to its consultation on the issue.

Instead, a voluntary code of practice will be drawn up, to ensure pupils are “kept safe” while further evidence is gathered on the need for compulsory registration in the future.

But Nye and Gill said that while they “will avoid here the question of exactly how much regulation might be appropriate”, they believe that “as a minimum, if a school or alternative provider is making use of currently unregistered alternative provision, that provision should in fact be registered with the DfE”.

The poor provision of AP is unacceptable and needs to be addressed and turned round. What a shame though that rather than focus on this the author tries to skew the story to fit their political narrative of how Councils are better at running schools.

I don’t know all the facts here (heaven forbid we’re given actual facts) but I’ve seen comments on another article that said since 1994 two thirds of PRUs have been closed. I’d go out on a limb here and say that the ones that were closed were rather more likely to be the Inadequate ones rather than the Outstanding ones.

In another Schools Week article it quoted someone as saying “Warwickshire council closed all of its pupil referral units in 2012”. I wonder how good Warwickshire Council were at running PRUs.

Imagine the indignant (and fully justified) uproar if an Academy Trust with 50 academies ditched the 33 academies with the worst Ofsted rating and then started trumpeting about how many of their schools were Outstanding.

It seems abundantly clear that we have a serious problem with AP, and taken as a whole the current approach of meeting the need with private AP providers doesn’t seem to be working. It seems equally clear that insinuating Councils are the only solution is not the answer.