Ofsted has published its annual report for the 2020-21 academic year.

Routine inspections have been suspended for large parts of the year, meaning the study lacks the usual data insights. Instead it provides a glimpse into what Ofsted has found in relation to how the pandemic has affected the sector, and how it is now reacting.

Here’s what we learned.

1. More primary pupils moved out of Ofsted’s view

Ofsted said it had “seen an increase in the proportion of pupils who moved out of the state-funded sector to other destinations”, including moves to independent schools, unregistered schools and home education.

But these pupils “cannot be tracked” through the data Ofsted holds.

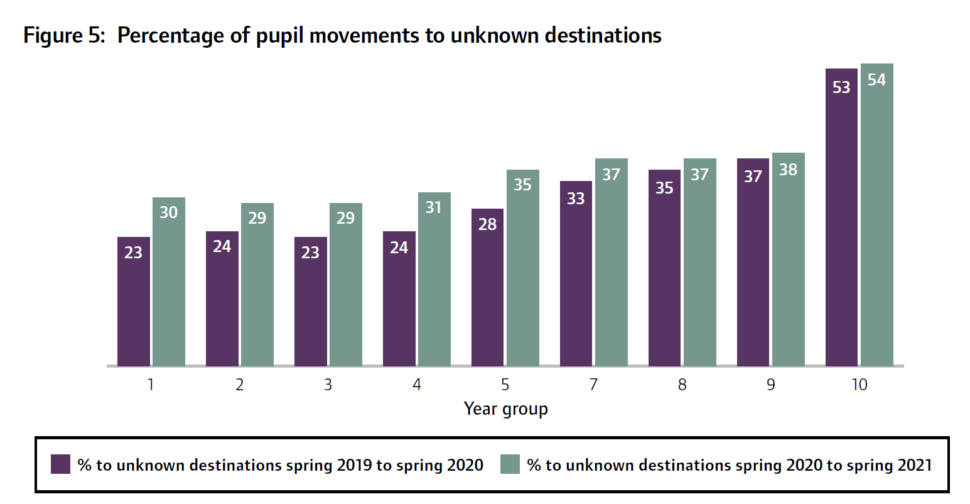

The report found that 33 per cent of pupils who left their school between January 2020 and January 2021 “moved to one of these ‘unknown’ destinations”, compared with 29 per cent the year before.”

This “may be a sign of an increase in home schooling but also moving overseas”.

The increase in the proportion moving to unknown destinations is greater for primary-age pupils than secondary-age pupils.

2. Reintegration of AP pupils ‘not a reality’

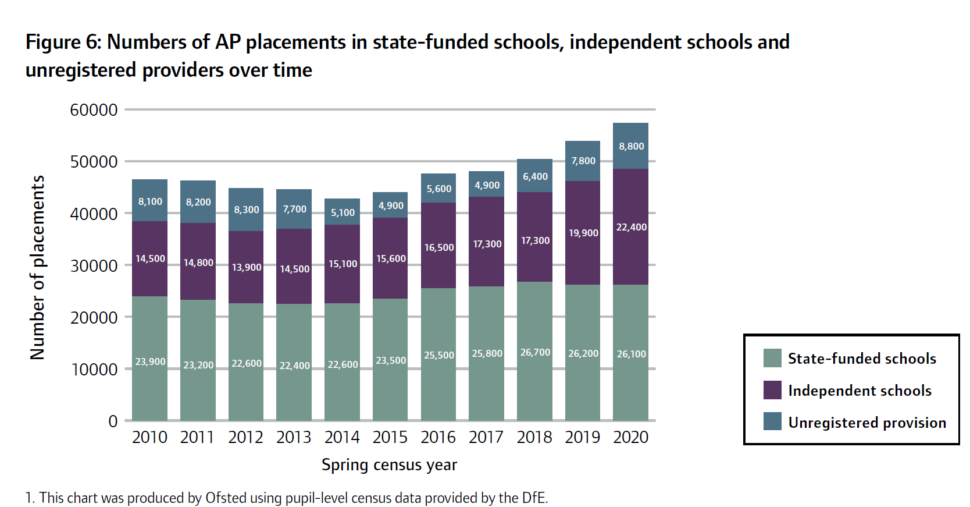

Ofsted pointed to a 78 per cent increase in the number of placements in independent schools, including independent special schools, commissioned by local authorities over the last 10 years.

It found there were now over 8,000 AP places for primary-age pupils, an increase of 55 per cent since 2010.

Three quarters of pupils in AP have not been excluded, but either continue to be registered with a mainstream school or attend full time at a pupil referral unit, academy AP or free school AP.

Statutory powers enabling schools to educate children off-site in AP include requirements on mainstream schools to keep placements under “constant review” and to reintegrate pupils back into mainstream “as soon as possible”.

However, Ofsted warned that this aim “does not translate into reality”.

Thirty-eight per cent of children stay in PRUs, academy AP or free school AP for more than a year.

And 58 per cent of those who join in Year 9 and 78 per cent who join in Year 10 are still there in the January of Year 11.

3. ‘Big gap’ in AP oversight

Although Ofsted inspects all registered AP, unregistered provision is “not directly monitored”, and the number of placements in unregulated provision “has been rising over the last three years”.

Unregistered school inspections have found “a number of APs operating illegall”, and “alarmingly”, the children with the highest needs are “particularly likely” to end up in unregistered providers. Sixty per cent of children in unregistered AP have an EHC plan.

“We cannot inspect unregulated AP, and so providers that cater for children with particularly complex needs are not systematically monitored. This is a big gap in our oversight and one that should be filled.”

4. Areas failed to rise to SEND challenge

The report found children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities had been “disproportionately affected by the pandemic”, and that “not all local areas rose fully to the challenge across all of education, health and care”.

Joint area inspections of SEND provision were suspended during lockdown, but restarted this summer. Of eight councils inspected in this reporting year, seven required a written statement of action, an “indication of significant weaknesses”.

EXCLUSIVE: Shocking reports detail how vulnerable children and their families left to fall into crisis

Overall, of the 123 areas inspected since the process was introduced in 2016, 66, or 54 per cent, have had to produce such statements.

Ofsted has to date carried out 29 revisits, including eight this year. Only 11 councils were found to be making progress in addressing “all significant weaknesses”, while 17 had only made progress on some, and one had not made progress on any.

“The next steps for areas that have not addressed all significant weaknesses are determined by the DfE and NHS England, and may include the secretary of state using their powers of intervention,” Ofsted said.

The government sent a commissioner into Birmingham to take over its SEND services this term.

5. Lack of SEND services left children ‘in pain’

Ofsted said SEND children and their families had reported “missed and narrowed education”, coupled with the absence of essential services and “long waiting times” for assessment and treatment.

Many in-person services were “cancelled or curtailed, including short breaks, physiotherapy and occupational therapy”.

As a result, some parents and carers reported that children had “regressed in communication skills and in wider learning”. In several areas, access to child and adolescent mental health services was a “particular concern”.

The lack of services overall left some parents and carers “feeling isolated, exhausted or unable to fill in gaps in support”.

Parents cannot be the driving force in ensuring that agencies work together, as they too often are

“Without access to their usual services, some children and young people with SEND were left in pain, immobile or unable to communicate properly.”

Ofsted said it hoped the government’s SEND review clarified “the purpose of the SEND system”.

It should also outline changes “that will result in SEND being identified accurately and early, embeds evidence-based provision that enables all children and young people to make the best possible progress, and clarifies the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of all partners in the system”.

“Parents cannot be the driving force in ensuring that agencies work together, as they too often are. This must be a cross-government effort.”

6. ‘Too much persistent poor performance’ in independent schools

Between the autumn term of 2020 and the end of the summer term this year, Ofsted carried out 350 additional inspections of independent schools at the request of the DfE.

Of these, 77 were progress monitoring inspections (PMIs) to schools that had previously not met the government’s independent school standards.

In these inspections, 51 per cent of schools continued not meet all the standards checked.

Ofsted also made 52 emergency inspections, in which 44 per cent of schools did not meet all the standards checked.

The report warned that “although most of the sector performs well, there is clearly too much persistent poor performance”.

7. Unregistered school reforms ‘slow to arrive’

In 2020/21, Ofsted carried out just over 100 inspections of unregistered schools and issued 24 warning notices.

It continued to support the Crown Prosecution Service with three cases that are before the criminal courts.

Since 2018, five investigations have been submitted to the CPS, resulting in successful prosecutions and the sentencing of 16 defendents.

However, Ofsted warned that although it had made “significant progress in tackling unregistered schools, there is no room for complacency or inaction”.

“Thousands of children in unregistered schools are still out of reach because of weaknesses in legislation and in our investigative powers. We welcome the commitments made by government to strengthen the legislation in this area, but they have been slow to arrive.”

8. ITE providers fail to make the grade

Ofsted introduced a new initial teacher education inspection framework this year. Inspections were suspended during the spring term, but started in the summer, when 36 age-phase partnerships were visited.

Of those 36 age-phase partnerships, one was judged ‘outstanding’, 16 were ‘good’, 12 were ‘requires improvement’ and seven were ‘inadequate.

However, Ofsted warned that the grades “may not be representative of the whole sector because it is a small sample, and we prioritised new providers not previously inspected and those not inspected for the longest time”.

Investigation: From ‘world’s finest’ to ‘inadequate’, teacher trainers fail new Ofsted test

“This also means that the evidence base is too small to make any comment on the effectiveness by type of provider.”

During its inspections, Ofsted found trainees were “particularly behind” in their experience of managing behaviour, and “many” in the primary phase had “limited experience of teaching early reading, including systematic synthetic phonics”.

Ofsted concluded that all trainees were likely to need some additional support in their first year of teaching “and possibly longer” to make up for these shortfalls.

Your thoughts