Katie Waldegrave’s charity, Now Teach, has won £3 million to go fully national. She explains why career switchers can have a radical influence both in and outside of the classroom.

If you’ve heard of Now Teach, the charity that supports career changers into teaching, it’s likely you’ll know one of at least one of its founders, Lucy Kellaway, who became the poster girl for the organisation after leaving the newsroom for the classroom.

But less well covered in the media is her co-founder, Katie Waldegrave. Did you know that before setting up Now Teach, Waldegrave had already been a teacher, set up another successful charity, published a critically acclaimed history book – and lectured in India?

Waldegrave recalls the moment this later stage of her career began, not long after she herself had had twins. “Lucy had met my mum at a party, and she was then thinking of becoming a teacher,” she says. “My mum said, you should talk to Katie!

“She came in the morning, and we talked and talked. By the time she left, Now Teach had probably been born.”

The pair discussed a book which had been published in 2016 called The 100 Year Life, which estimated that about half of babies born since 2000 might live to 100 years old. They reflected on the babies, the book and “talked about the profound changes in the ways people were experiencing their lives and their work,” says Waldegrave.

The conclusion: a new model for entering teaching was needed – one that did not assume young graduates were the obvious recruits into the profession.

In a way, if Kellaway represents the late career switcher, then Waldegrave represents the other side. Her varied career is perhaps closer to the flexible, multi-role route that commentators tell us is the future of work.

She joined Teach First’s inaugural cohort in 2003, after having come from what she describes as a “very privileged background.

“I lived in the proverbial bubble,” she says of her early life, with admirable frankness. “I went to private schools, and then to Oxford, and that didn’t seem particularly surprising.”

There was one particularly unusual aspect of Waldegrave’s life, even compared with her peers: her father, now Lord Waldegrave, was health secretary to Margaret Thatcher and John Major, and MP for Bristol West.

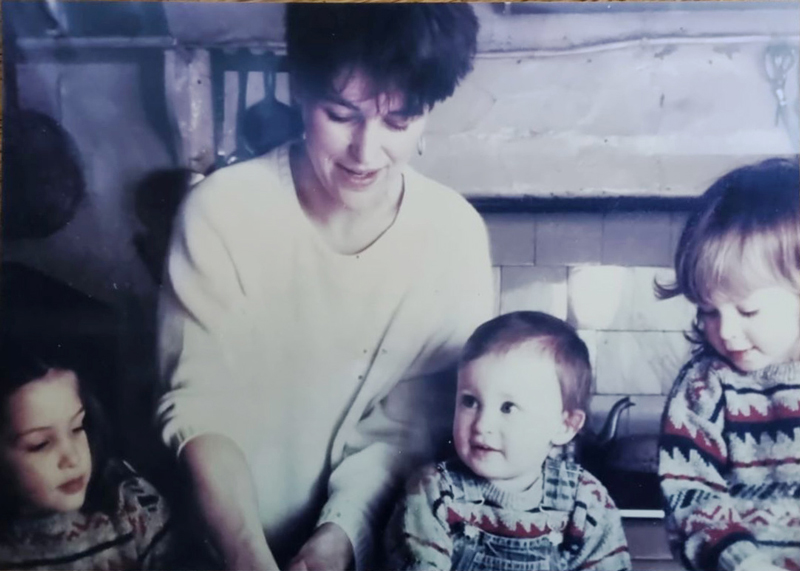

“We had a split life, between London and Somerset, so I lived between these two worlds,” she says of herself and her siblings. They lived in a big, old, “dilapidated” house, with Waldegrave’s mum constantly “in overalls” trying to fix things while also successfully running a cookery school with chef Prue Leith.

“I remember Mum had this bell she’d ring, and we’d all arrive, covered in mud! I was a very free child.”

Her father, who is regarded as being on the moderate wing of the Conservative Party, also instilled a sense of public service in Waldegrave. “It was a deep and ingrained sense that if you can, you should give back in public service.”

Nevertheless, Waldegrave’s career does look different to her father’s: she has worked in challenging schools in deprived areas, while Lord Waldegrave is now the provost (chair) of Eton College, where he was also a pupil.

His public comments show he is a strong proponent of bursary provision, but he got into hot water the same year Now Teach launched when he threatened to resign from the Conservative Party over government plans to make employers ask job applicants if they went to private schools. The plan was quickly dropped.

But again, Katie is being somewhat overshadowed.

It’s partly her modesty: she tells me in passing she once wrote a “totally irrelevant book”, whereas it’s called The Poets’ Daughters, is about Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s daughters, and received glowing praise from the Sunday Times, Observer and Spectator.

Similarly impressively, in 2007, she set up a creative writing charity with award-winning author William Fiennes, called First Story, which now reaches about 170 schools. Then in 2013, she and her husband moved to India, where she lectured at Ashoka University in New Delhi.

That same modesty made Teach First a slightly uncomfortable experience all those years ago, while she was teaching at Cranford Community College in Hounslow, west London.

“It didn’t always feel straightforward. I didn’t realise how controversial it still was in the staffroom. And I think I personally also felt acutely conscious of being this girl with the posh voice.”

Career changers know how to be efficient and prioritise

What’s really interesting about Waldegrave is her insight into enticing the very young, and inexperienced, into teaching – and how it has shaped her view that career changers could really be the more radical cohort to bring into schools

“One of my pet theories is that because teaching remains such a young profession, people are working every hour that is possible. I certainly was, and so was everyone else,” she says.

But “career changers know how to be efficient and prioritise. They know when to say, actually, ‘what I’m doing now is no longer helping. I should sleep.’”

She makes an important point. Figures from 2019 show just 67 per cent of early-career teachers remained in the profession five years after they joined. One in three teachers last year planned to quit within five years, citing workload.

It’s here that the value, and radical potential, of Now Teach emerges – it is called Now Teach, rather than Teach First.

“I would love to think that Now Teachers could support colleagues by setting a different model that says, ‘I will be good enough’,” smiles Waldegrave.

So far, the charity’s track record is promising.

A report by ImpactEd found 76 per cent of Now Teachers remain in the profession after two years, compared with 39 per cent of other trainee teachers the same age. Meanwhile, 93 per cent of Now Teachers are still in teaching one year after qualifying, compared to 85 per cent nationally.

The numbers are small, though. Of the roughly 6,000 people who joined ITT programmes this September, only 168 were with Now Teach. But that’s rising to 200 in 2022, and 250 the following year.

She adds: “If you’ve been doing something else well for 30 years, this is very hard in a different way, [but] there’s something about being a bit braver.

“When I was 23, I might have moaned, but I would moan to my mum. But if you have seen the way other places are, you can have a little more confidence about pushing back against things that are not reasonable.”

This point is particularly relevant with the shift to flexible working in many other sectors, which doesn’t seem to be mirrored by schools yet.

Waldegrave is conscious, as ever, of not sounding pompous: “The last thing you want is Now Teachers coming in and saying ‘do it this way’.” But many Now Teachers “have signed off on flexible working, so they know how to ask for it”.

And there are some brilliant stories: she tells me of one former NASA scientist who “rearranged the footflow” of his school so children stopped jamming the corridors. Another Now Teacher reworked data input, so it took staff minutes rather than hours.

It is this potential that Waldegrave wants to scale up, using the charity’s £6,600 per recruit (for one year of marketing, and two years of support).

“Where next will be how we capitalise more on what’s happening organically, and amplify Now Teachers.” With £3 million in government funding to go nationwide from September 2022, the goal is to have a “Now Teacher in every staffroom”.

The goal is to have a Now Teacher in every staffroom

With the potential of career changers in mind, Waldegrave also has her eye on strengthening them across the public sector. She’s been advising two Frontline alumni (the Teach First for social workers) to create a similar programme for foster carers, also aimed at older, experienced people.

“It would be great to have a big network of career changers all over,” she smiles.

As someone who has successfully taught, written, and set up charities – resulting in her MBE this summer – Waldegrave understands the reality of the 100-year life perhaps better than most school leaders. She’s definitely on to something with the radical power of career changers.

“Now Teachers see things differently,” she concludes. “If you went school-university-school, you might just think this is what work is like.”

Your thoughts