Two former school teachers founded the Centre for Holocaust Education at the UCL Institute of Education. They tell Jess Staufenberg why understanding complicity is a big part of their work

“I didn’t set out to become a teacher of such a disturbing history.”

Ruth-Anne Lenga, a former RE teacher, didn’t expect her life to take such an unusual turn when she left the classroom in the late 80s. She had joined the Jewish Museum in London as head of learning, helping with exhibitions about Anglo-Jewish life: the bakeries, East End, vibrancy of culture.

One day, a man walked in. He had hollow cheeks and took Lenga’s hand in an iron grip.

“This was no ordinary man – this was the most compelling individual you would ever have met,” smiles Lenga.

In the man’s other hand was a suitcase – and inside were objects he had hidden with neighbours when he had lived in Holland at the start of the Second World War.

They included his wife’s wedding dress and little shoes for his two-year-old son, Barney. “He was telling us we had to put on an exhibition about the Holocaust, and his life.”

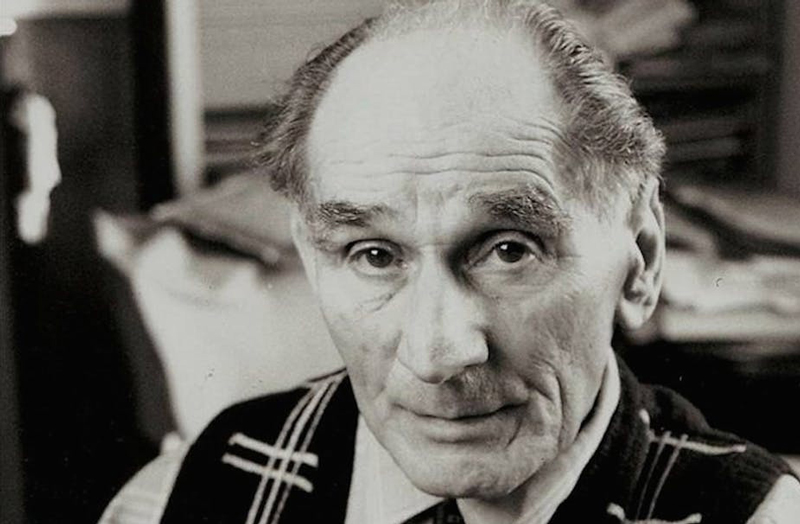

Leon Greenman, then in his 80s, was born in Stepney Green in east London, but in the 1930s moved with his wife and son to Rotterdam. When Germany invaded in May 1940, Greenman took their most important belongings and divided them between his two neighbours, asking one to keep his identity documents and English currency safe, so he could get his family back to England.

“But the neighbour betrayed him,” Lenga says. “Out of fear of being caught helping Jews, they burned the passports and the money disappeared.”

In October 1942, Dutch police raided Greenman’s home, arrested his family and took them first to Westerbork transit camp in the northeast of the country, and then transferred him to Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland – the largest Nazi death camp. When he was freed in 1945 from Buchenwald camp, he was recorded in an interview saying: “I don’t know where my wife and child are.” He later found they had been murdered.

Last week was the 80th anniversary of the Wannsee Conference in Berlin, in which senior German government officials signed off the “Final Solution to the Jewish question”. Yesterday marks the day Soviet troops liberated Auschwitz, now called International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

But this week the Auschwitz museum director in Poland warned “the biggest task for remembrance today is to combat indifference”.

Iron-bent on that mission, Greenman began talking to students on the RE PGCE that Lenga was leading in the early 1990s at the Institute of Education. In the complex discussions that would follow, she noticed she’d get the same comments every year from trainees about how this encounter with a survivor was the most profound part of the course. “They said it showed them why they needed to be a teacher.”

The set-up caught the attention of Professor Stuart Foster, a former secondary teacher who was leading the history PGCE at the institute.

The Holocaust has been mandatory in the national curriculum since 1991, following the 1988 Education Reform Act under Margaret Thatcher, but it was Gordon Brown who agreed more awareness was needed. Lenga and Foster teamed up and secured funding for their Holocaust Education Development Programme for teachers in 2008.

Their first task: finding out the current state of teaching about the Holocaust. In 2009 they surveyed 2,108 teachers, and ran interviews with 68 teachers across 24 schools.

“We found that teachers were teaching what we call a ‘perpetrator narrative’ – ‘this is what the Nazis did to the Jews’,” says Foster. “But who were the Jewish people of Europe?”

Lenga explain: “Only by exploring their hopes, dreams, lives, ordinariness, only then can anyone get a sense of the infinite possibilities that are lost when you murder 1.5 million children.” Two-thirds of European Jews – six million people – were murdered in the Holocaust.

“If you go into a bookshop and look at textbooks about the Holocaust, many will have the face of Hitler on them,” Lenga says.

To counter that “perpetrator” narrative, the team produced a free key stage 3 textbook, 50,000 copies of which have gone to schools, called Understanding the Holocaust. The cover shows seven grinning children on a seesaw, enjoying a hot day in Hungary: the lives of ordinary Jewish Europeans before the Shoah – the “catastrophe”, as the Holocaust is in Hebrew.

In 2012, Michael Gove doubled the team’s funding to an annual £500,000, match-funded by the Pears Foundation, led by philanthropist Sir Trevor Pears. The Centre for Holocaust Education was launched, now offering a module for initial teacher education courses, a masters’ module, and the new beacon school award (in which the centre works closely with a school over one year).

The school award attempts to undo many misconceptions the centre found in a survey of pupils in 2016. Of the 7,952 key stage 3 pupils surveyed, 65 per cent didn’t know what “anti-semitism” meant, 10 per cent thought that fewer than 100,000 Jews had been murdered – while 56 per cent thought Hitler was solely responsible for the Holocaust.

“How do you get students to understand that genocide is a societal thing? Massive amounts of people have to be complicit,” Foster says. Leon Greenman’s story was used as a springboard for discussion.

“We ask students, who killed Barney Greenman?” Lenga says. It sets me thinking: Leon Greenman’s neighbour betrayed him, Dutch police arrested him, he was taken into Poland. “We focus on teaching about complicity and collaboration.”

We ask students, who killed Barney Greenman?

How does the team prepare teachers for the tricky questions that must follow? Such as how the UK treats refugees today (one charity has said the government’s treatment of refugees amounts to “performative cruelty”). Or is this British history if it wasn’t on British soil? Foster nods: many of these questions have been raised with the proposal of a Holocaust memorial in Westminster.

“It’s about it being central to European history.” The Holocaust shows there are things we must always learn, regardless of whether they are “British” events or not.

Teachers must also be ready for questions about Palestine and Israel. Last year, as antisemitic incidents rose, then-education secretary Gavin Williamson warned heads to ensure “political impartiality” over the conflict and occupation.

“It’s complex enough teaching and learning about the Holocaust, without going into anything else,” Lenga says. “One needs a robust knowledge base to engage in these conversations – even just with the Holocaust, you need to know so much.”

Foster agrees that big questions arise: “The core issue is the responsibility we have to other people. How far do we care about Syrian refugees, what’s going on in Yemen?” This Wednesday, the Auschwitz Pledge Foundation was launched to fund projects that fight indifference to hatred in societies.

The centre has done admirable work through its beacon school award. Remote schools in areas of little ethnic diversity, such as Torpoint Community College in Cornwall, are involved, as is Rockwood Academy in Birmingham, which has a predominantly Pakistani roll. Pupils there named a new building after a Holocaust survivor they had met.

And the work is needed. Foster points out the national curriculum is not compulsory for academies, and only a third of pupils take history GCSE, with just 6 per cent at A-level.

“Aside from us, only Albania stops teaching history at 14 in Europe,” he says. We are at risk of forgetting.

Legna remembers one survivor telling a group in Sheffield about his guilt at the relief he felt when someone died beside him in an airless cart, giving him more room to breathe when the body was removed. “A student said to me, I wanted to go up to him and reach out, and just say, ‘it’s not your fault’.”

It is these human encounters with survivors that make the deepest difference – just as it did when Greenman met Lenga all those years ago.

“What sort of textbook could have done that?” she asks. “That young 14-year-old, showing that level of understanding of agony. How could a teacher have done that?”

But, crucially, these survivors will be gone one day. It means the centre’s most important days – absolutely critical days – still lie ahead.

Your thoughts