Anne-Marie Canning knows what it’s like to have all the odds stacked against you, get good grades, and still not get a place at a highly selective university. Working with parents can change that, she tells Jess Staufenberg

“I still get phone calls from people in my village, saying, ‘My mum met your mum in the supermarket, and she says you might be able to help my son go to university.’”

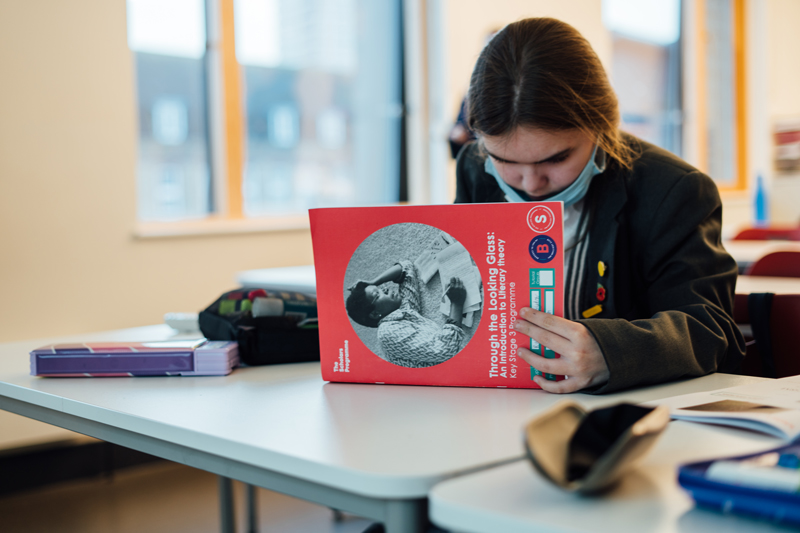

I’m talking to Anne-Marie Canning, chief executive of The Brilliant Club, a charity that trains and pays PhD researchers to tutor disadvantaged pupils to help get them into top universities. It’s one of the many spin-off social enterprises founded by former Teach First graduates, in this case in 2011 by Jonny Sobczyk and Simon Coyle.

The pair stepped down in 2017 and handed over the reins to Chris Wilson, a Cambridge University graduate who had been with the charity for five years.

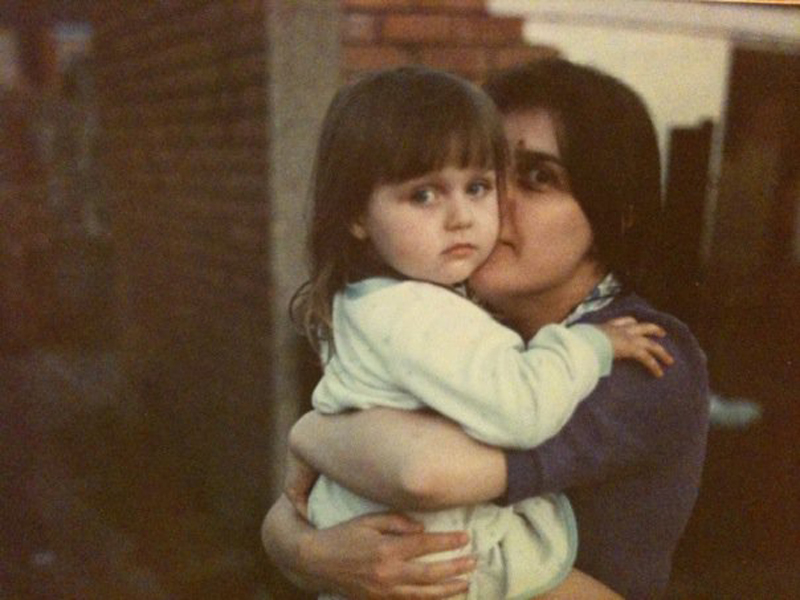

Now it’s the turn of Canning, who despite getting a place at summer school for Oxford University while a teenager was painfully rejected for an undergraduate course. Her experiences growing up in a working-class community – the northern ex-mining village of Carcroft – perhaps explain one of her key targets for engagement: mums.

If the first five years was to establish The Brilliant Club’s Scholars Programme, and the next five years to prove impact, Canning says the following five years under her stewardship will be about “throwing open its doors”.

The Brilliant Club may be based in schools (it sends PhD researchers into about 900 schools) but it is the community around schools Canning has her eye on.

Like the phone calls she keeps getting, the story starts in a Yorkshire village. “I used to tell a very sanitised version of where I’m from, saying that I was from Doncaster. But that’s a really big town with good train connections, whereas I’m from a pit village, where it was pretty rural, and the pit got closed.”

Canning’s father had been a miner before becoming a lorry driver, and her mum worked for the National Coal Board and was disabled.

Canning looked after her mother, and also attended North Doncaster Technology College (“the worst school in Donny”) which, according to Canning, at the time had 2,500 pupils, only 17 per cent of whom were getting A* to C grades at GCSE (nowadays it’s Outwood Academy Adwick, and results have improved).

Despite this, Canning applied to Oxford University’s summer school aged 17 – and was accepted. When she worked at the university some years later, a colleague revealed they had received her form: “They said it was the only application they ever accepted late.”

But despite the exciting box of books that arrived beforehand as reading material, the actual experience also made her angry. “I realised the nature of inequality in education.” She leans in to explain the “crystallising moment”.

“A fellow student said, ‘When we apply, I don’t mind which of us gets into Oxford, because we’ve all worked equally hard’. And I thought, ‘Well, I mind. I don’t have a teacher in all of my A-levels, so my grade A in my A-level is a bit different to yours.”

Canning took five A-levels, but her school had a staff shortage and couldn’t appoint teachers for two subjects.

Another tough lesson arrived next when she was rejected from a place to read English literature at Oxford. “That is hard, because I was the first to apply from my community and you’re held up as a totem. It’s like, ‘If she can’t do it, who can?’”

Instead, she broke barriers by becoming “the first student union president at York University with an actual Yorkshire accent”.

After graduation, Canning went to work at Oxford University as an access officer “to try and crack this thing”. She says she was its first ‘outreach professional’ and even won a prestigious Oxford teaching award for her work with schools.

Wanting to be somewhere “more radical”, Canning then joined King’s College London, becoming director of social mobility and student success. She moved the university to a “fully contextualised admissions system”, which she says was “about making the starting point for admissions, ‘how do we offer a place to the student?’, rather than ‘how do we reject them?’. Too many admissions systems are about prize giving.”

Statistics suggest the problem is way off being solved. Deprived pupils have only a one in 50 chance of accessing the most competitive universities, compared with one in four for the most advantaged pupils. Meanwhile, the “access gap” for top universities between pupils on free school meals compared with their peers has widened since 2010.

Moreover, since Covid hit (Canning started at The Brilliant Club on the first day of lockdown), policy shifts have made the charity’s work even more relevant.

First, the pandemic ushered in a big public focus on tutoring with the arrival of the National Tutoring Programme (NTP). According to Canning, The Brilliant Club is its largest non-profit provider, winning a contract with the Department for Education to tutor 8,000 pupils last year, and aiming to tutor 7,000 students in 2021-22 and again in 2022-23.

“We thought it was the moral and ethical imperative,” she says, adding families are now increasingly anxious to access tutors. “Parents know all the parents are doing it, and that they can’t afford it, and that’s devastating. They know the game and they’re distressed for their kids about it.”

The National Tutoring Programme could be as loved as the NHS

Many are working second jobs to afford a tutor, she says, and some parents have even asked Canning which child to pay tutoring for, because they can only afford one. This all means “the National Tutoring Programme could be as loved as the NHS,” says Canning – a message she took to the Conservative Party conference last year.

But she is frustrated that administration of the NTP moved from the Education Endowment Foundation to the for-profit HR firm Randstad, which is accused of presiding over a low take-up of tutoring this year. Some of the best-known tutoring providers were late to re-join the NTP this year amid a contract stand-off with Randstad.

“My big worry is that parents who have never had access to a tutor

before are now losing faith in tutoring,” Canning warns.

This is where her focus on parents comes in. As chair of the DfE’s Bradford opportunity area – a government scheme to boost social mobility in 12 targeted areas – Canning recently helped introduce funding for mums on a housing estate to take learning materials from school direct to other parents. And families from her old village regularly ring her to ask for help getting into university.

“These are mums who are meeting my mum in the veg aisle. They sniff out my mum in Asda, and she doles out my number! It shows the power of the maternal working-class mum.”

Now Canning has partnered The Brilliant Club with Citizens UK, a charity that supports community action, to set up ‘parent power’ chapters where parents can ask and get support about university access.

There are five groups, each with a university partner: Cambridge, Cardiff, Liverpool, London (with King’s College) and Oldham (with Manchester University). “The idea is to have parent power chapters all across the UK – a sort of Mumsnet in person for working-class folk,” says Canning. “If you invest in a parent in that way, it spreads to other parents.”

This is The Brilliant Club under Canning: bringing the community in from the cold, and getting universities to help her do it. She’s had to make some tough decisions along the way: whereas the charity provided a teacher training route for PhD students from 2014, Canning axed it.

It’s all part of her strategy – to focus completely on both student access into university and student success once at university. For the latter, she hopes to better mobilise the charity’s network of PhD tutors to prevent more students dropping out of their courses.

And where Canning leads, the government follows. In November, universities minister Michelle Donelan told universities to rewrite their access and participation plans to focus on improving outcomes for poorer students and working with schools. “This is a big regulatory change, and we’ve got a lot of universities coming to us,” notes Canning.

So with universities keen to sign up, Canning’s focus on hard-to-reach parents as a priority sounds wise. “A common thing across my career is a belief in parents,” she says. “If there’s one thing we should be encouraging parents to do, it’s telling their kids what they dream of for them.”

Your thoughts