Stephen Morgan is the fifth shadow schools minister in two years, and he wants the sector to know he’s sorry.

“What I’ve been saying to people is that I’m really conscious of that, and I apologise for that, because they will probably feel like they’re having deja vu moments where they’re repeating what they’ve told my predecessors.”

The Labour MP for Portsmouth South succeeded Peter Kyle in Sir Keir Starmer’s front bench reshuffle in December.

But unlike his predecessors, Morgan tells Schools Week in his first interview since taking the role that he’s in it for the long haul.

“Keir said that’s his team that he wants to take through the next general election, whenever that might be… Hopefully I’m the last shadow and the next schools minister in the Labour government, and that’s what my focus is on.”

When we meet in his constituency office, a former hot dog restaurant a stones-throw from his old secondary school, Morgan explains how his own education had a big impact on his politics.

Morgan grew up in the district of Fratton, Portsmouth, in the 1980s and attended state schools. His father, a silk-screen printer, and his mother were school governors and “very involved in the local community”.

Morgan’s interest in politics piqued when, at an early age, a family friend gave him back issues of the Guardian to read. “I wouldn’t read a book at school, I’d read copies of the newspaper. And that probably shaped my politics.”

Growing up in “Thatcher’s Britain”, Morgan remembers learning in “crumbling” Victorian schools, and a “lack of care and attention” for education from government. He joined the Labour Party in 1997 at the age of 16, “with that hope of a Labour government that would transform our country and prioritise education”.

Morgan ‘inspired’ by his teachers

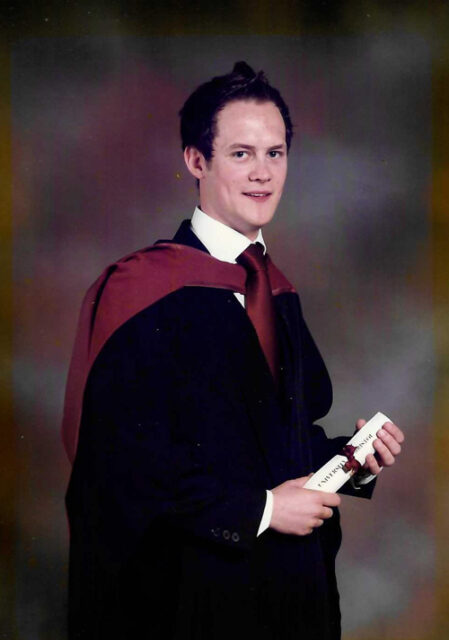

“Inspired and encouraged” by his teachers, Morgan went on to become the first in his family to go to university, reading politics and sociology. He arrived at Bristol University with his belongings in bin bags, while other students turned up with trunks bearing their family emblem.

“I guess, coming from a working-class family, it was never seen as something that people like me would do. But it was my teachers who said, ‘If you want to go far in life, then this is absolutely something you should pursue’.”

He considered a career in teaching but was discouraged by the “workload and challenges” faced by his own teachers.

After a Master’s at Goldsmiths in London, Morgan worked in local government, initially for Portsmouth City Council and then in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

He said he had never considered becoming a politician, but seeing his grandfather, a D-Day veteran, not receiving the social care he needed at the end of his life inspired him to get involved.

After moving into the voluntary sector as chief executive of a charity in Basingstoke, Morgan ran for Portsmouth City Council, where he won a seat in 2016. Theresa May called a snap general election the following year.

“I said to my trustee board, ‘Look, there’s a general election. It’s my home city. I’ve always wanted the opportunity. And Labour won’t win, because we’ve never won that seat before.’ And they said, ‘Yeah, we’ve looked at the statistics, there’s no chance of you winning, have two weeks annual leave and off you go’.”

Morgan went on to win the seat in 2017, and trebled his majority in 2019.

Part of the victory he puts down to demographic change. Portsmouth is more “diverse and cosmopolitan” than it was, and Morgan believes Labour was also finally seen as an alternative to the Conservatives in the area. Its policy offer also cut through, he believes.

School funding campaign hit home in 2017

Another impact in 2017 was the party’s campaigning on school budget cuts, and Morgan worked with unions “on calling the government out on cuts to city schools”.

He believes education will be a “battleground” at the next election too. Despite recent cash-terms uplifts, funding is still an issue raised by leaders he speaks to. Staff burnout is also a big concern. “At every school I’ve been into in the last few weeks, heads and staff have said this is the worst it’s ever been in terms of morale.”

Morgan joins the shadow education team at a pivotal time for schools. The government’s much-delayed SEND review and a promised schools white paper are both expected in the first half of this year.

This will force Morgan to confront a difficult policy area for the party – academies. While much of Labour’s grassroots still wants them returned to local authority oversight, the party has in recent years softened its stance, saying those academies that do well will be left alone.

Although Morgan says the party still has concerns about accountability, he believes any reforms of the school system must be about “outcomes not structures. I don’t think we would want a whole-scale restructuring exercise. It would be the wrong time to do that.”

Education to be ‘front and centre’ of manifesto

One criticism levelled at Labour in recent years is that the party has often dragged its feet on announcing firm policies, and failed to paint a coherent picture of what education would be like under a Labour government.

Rebecca Long-Bailey, who served as shadow education secretary between April and June 2020, admitted at the time that the lack of an “overarching message” from Labour on its flagship National Education Service was one of the reasons it lost the 2019 general election.

Morgan wants to put education “front and centre of our manifesto”, but voters will have to wait still to hear the party’s full policy platform.

“We’re certainly as close to the next election now as we are the last. But we wouldn’t set out our retail stall halfway during the parliament – we would do that much closer to the election.”

But Labour isn’t starting from scratch either, he says, and policy development work by his predecessors and the party more widely will be factored in. “I don’t think we are starting from a blank sheet of paper, and I’m proud to be in a democratic party where we’ve got huge amounts of members who have particular views on these issues.”

Aside from its own alternative education recovery plan, voters were offered a brief glimpse at some of Labour’s proposed reforms at last year’s party conference. Starmer renewed the party’s commitment to scrapping tax breaks for private schools, pledged to offer more extra-curricular activities and to introduce two weeks’ compulsory work experience.

The Labour leader also pledged to reform Ofsted to include a school improvement role, abandoning plans set out under Jeremy Corbyn to replace the inspectorate entirely.

Ofsted ‘shouldn’t be a stressful process’

On Ofsted, Morgan says he wants to take the “stress” out of the process. “What teachers are saying to me is that often inspections are not a pleasant experience, that so often, they’ve made a view of what they want the report to look like and then just go in to find evidence of that. And that cannot be right.

“I think there’s better ways to do school improvement work. It shouldn’t be a stressful process, it should be a journey for improvement with the school and inspectors.”

But asked whether the National Education Service – Labour’s umbrella term for its education reforms under Corbyn – will feature in the next manifesto, Morgan says no decision has been made.

“What I want to do in my brief is talk in everyday terms about the impact of Labour government will make to children’s lives. So what does that mean in reality for a child who’s struggling at school, or a parent that wants her son to succeed?

“I’m not wedded to any particular models. It’s got to be about outcomes, improving people’s lives, about enriching their experience of school so that they can succeed. Badges don’t mean anything. But real, tangible policies that will make a difference, of course, do.”

Your thoughts