Schools across most of the country have fewer mentors than teachers who need them under new early career framework (ECF) training reforms, figures show.

Some areas have almost three early career teachers for every two mentors, with the biggest gaps in a swathe of towns across the north-east and north-west.

The gap is likely to raise fresh questions about staff capacity to deliver one-to-one mentoring amid worries about ECF workloads.

However mentors can have more than one teacher, and the figures could be a sign of success in the system, one expert said. It’s expected the discrepancy between mentors and ECTs may also grow as mentors support new teachers over multiple cohorts.

New government figures show at least 26,927 teachers started provider-led induction this academic year, the first that ECF training has been rolled out nationally for new teachers.

Ninety-five per cent of these are on courses offered by government-approved providers – which ministers are likely to welcome as a huge vote of confidence in the training they are providing.

More than 1,500 started school-led induction programmes based on the ECF.

But the number of mentors trained as part of provider-led programmes is 24,895, leaving mentor numbers more than 2,000 lower than teachers.

The Department for Education does not require staff to only mentor one colleague, but Teach First, a lead provider, recommends it “to support with mentor capacity and workload“.

Mind the regional gap

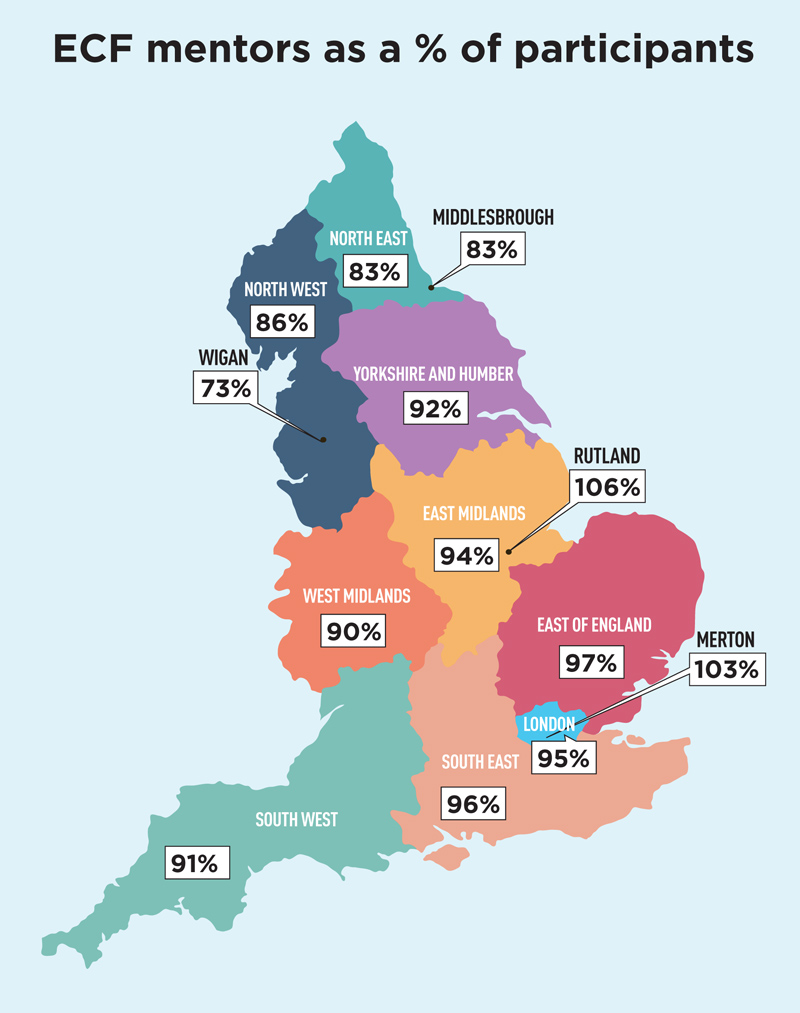

Schools Week analysis reveals significant regional and local divides in mentor-participant ratios.

The north-west had the highest gap in absolute terms with 482 fewer mentors than mentees, though the north-east – with fewer participants overall – had the highest gap in percentage terms.

North-east mentor numbers were 83 per cent of participant numbers, compared to the East of England where the figures stood at 97 per cent.

Among individual authorities, Birmingham had the biggest absolute gap, with 106 fewer mentors than participants. But this partly reflects its size as one of the biggest council areas, with many bigger gaps in percentage terms in many authorities.

A third of areas had fewer than nine mentors for every 10 participants, with the lowest mentor:participant ratios in Middlesbrough (70 per cent), Wigan (73 per cent), Bradford, Sunderland and Bolton (76 per cent).

Among the 25 areas with the fewest, 17 were in the north-east and north-west.

In total, 131 of 152 areas had fewer mentors than participants. Just nine had equal numbers, and 12 even had more mentors than mentees, including Rutland, Merton, and Surrey.

Signs of strain or success?

Professor Sam Twiselton, a teacher training expert at Sheffield Hallam University, said areas having fewer mentors than participants “might suggest a stress in the system”, with time, resources and competing priorities limiting mentor numbers.

Time and workload have been repeatedly flagged as a concern among staff already mentoring. Previous Teach First analysis has suggested that on its programmes, “the majority of mentors were not able to accommodate the programmes with their existing workload”.

A source at one lead provider said apparent shortfalls could reflect retention rather than recruitment issues, and indicate staff leaving schools rather than just the programme.

But experts say more analysis could be useful, as shortfalls may not always indicate a problem. If mentors are supporting more than one teacher at a school or trust, it can often be a “sign they’ve got themselves really well organised, and it’s a really big part of their job”, according to Twiselton.

Larger trusts in particular may have the resources to give some staff the time to take on multiple mentees, whereas in smaller schools it could be more likely to reflect stretched resources.

Some cash-strapped schools could also be deterred by funding arrangements. Teach First has noted schools “need to dig into their reserves” to cover the cost of releasing mentors for training and mentoring, despite budget pressures, as DfE extra funding only comes at the end of the two-year-programme.

The NPQ courses most in demand

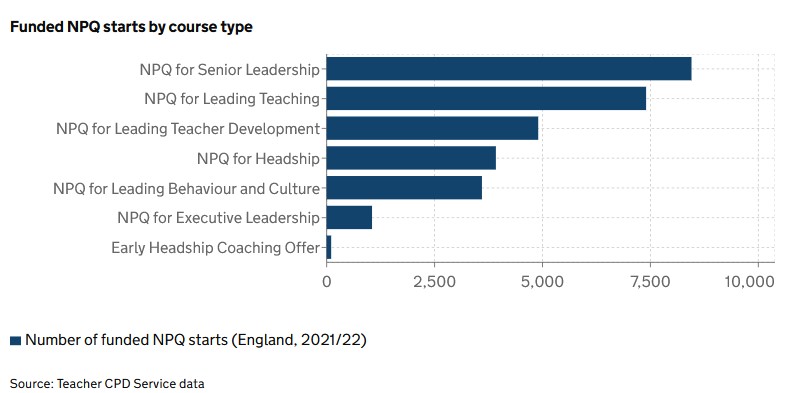

The DfE also released data on takeup of its reformed suite of national professional qualifications. It committed £184 million last year to provide 150,000 NPQs for more experienced teachers and leaders over three years.

Regional divides were also evident, with takeup of funded courses varying from 4.6 per cent in the East of England to 6.5 per cent in the North East.

In total 29,337 staff took funded NPQs in 2021-22, and another 1,681 took them who did not receive funding. The most popular training was in senior leadership, followed by leading teaching, and then leading teacher development.

The least popular was the early headship coaching offer, for heads in their first five years, which just 104 participants took. However it is only open to heads who have already completed or are currently completing the more popular NPQ in headship, suggesting numbers may increase in future years.

New schools minister Will Quince said it was “great to see so many teachers taking part in our world-class professional development programmes”.

“We’re on track to deliver half a million teacher training opportunities by 2024, giving teachers the expertise and support needed to deliver great teaching.”

Your thoughts