More than nine out of 10 school leaders say the early career framework (ECF) has created extra workload for new teachers, with concerns mentors are also “drowning” in work.

The ECF is a flagship government reform that provides a two-year package of induction for new teachers. The £130 million-a-year scheme was piloted last year and rolled out nationwide this September.

Teachers get a five per cent timetable reduction in their second year in the classroom for development, and more experienced staff should be freed up to be mentors.

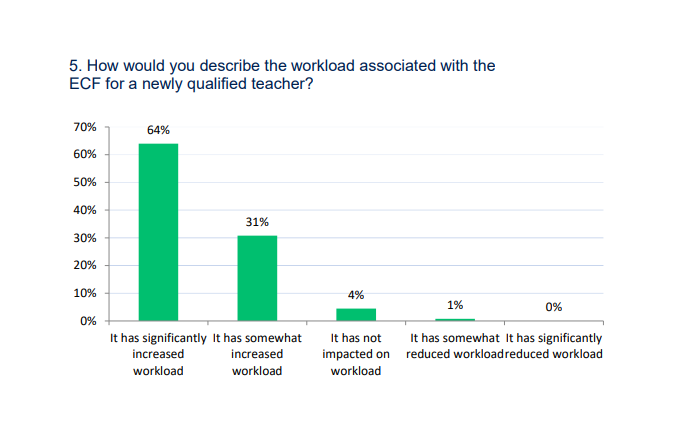

But a survey of 1,003 headteachers by school leaders’ union NAHT found 95 per cent felt the reforms had increased workload for new teachers.

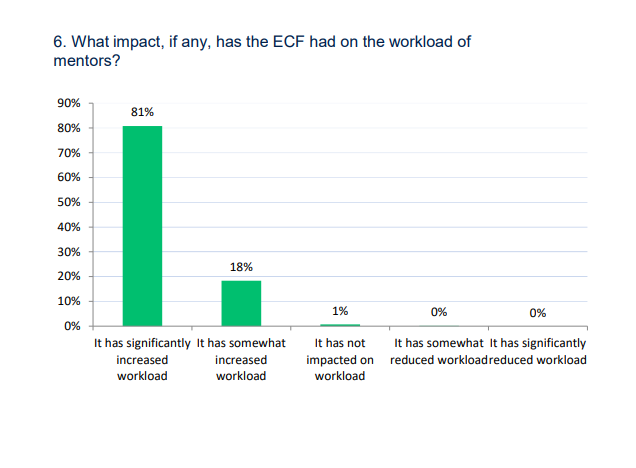

Nearly all leaders surveyed said the ECF had also negatively impacted the workload of mentors, with four in five saying the increase was “significant”.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary, claimed mentors are “drowning”. Just over a quarter of those surveyed – 28 per cent – reported that mentors did not want to continue with their roles as a direct result of the ECF impact.

“What’s needed is immediate action to create flexibility in the programme to allow early career teachers and mentors to focus on what matters most for their individual contexts,” Whiteman added.

The survey also found a third of leaders feared the new pressures would have a negative impact on new teacher retention rates.

The Department for Education said it is “committed to gathering evidence about the implementation of the ECF, including any impact on workload, to ensure we maximise the impact of these reforms”.

Despite the concerns, leaders generally supported the changes. Fifty-five per cent agreed with a two-year – instead of one-year – induction for new teachers.

Nearly half felt the reforms will have a positive impact on the professional development of new teachers.

Whiteman added the changes had “great potential” but demanded changes to get “workload and impact on work-life balance under control”.

If not, he added it could “end up doing considerable damage to retention rates, even as it tries to improve them”.

Schools can deliver the ECF through funded provider-led programmes, do their own training using DfE-accredited materials or design their own ECF-based induction.

Nearly 90 per cent of respondents were using one of the six approved providers. Just five per cent used DfE-materials and two per cent designed their own.

Zoe Shepherd, assistant headteacher at Beaumont School in Hertfordshire, said it was proving a “challenge” for mentors to find time to both study ECF resources and be the “experienced ear” for new teachers at hard times. They are using the provider-led route.

She added: “For some ECTs this is what could make the difference between them staying in teaching or leaving feeling burnt out. We need flexibility to support each teacher as an individual because depending on their ITT and previous experience, they start in different places.”

Faye Craster, a director overseeing the ECF for one of the providers Teach First, said last month teacher development “has to be at the expense of something else”.

NAHT wants DfE to review providers’ practices to ensure that programmes can be delivered and managed within the working day.

All six providers were approached for comment.

Jonny Uttley, chief executive of The Education Alliance (TEAL) trust which is delivering its own programme, said this allows “flexibility” to “deliver sessions to suit the needs of our schools”.

For instance, all mentor training was delivered before the start of the school year.

Dame Alison Peacock, chief executive of the Chartered College of Teaching, said the ECF has the potential to “stem the tide” of new teachers quitting.

But she said “we cannot be in a position where the reforms intended to help make things worse”.

A DfE spokesperson added: “After a challenging time during the pandemic, making sure new teachers receive high quality training and support at the start of their careers is more important than ever – helping them to build their skills and confidence early on.”

Your thoughts