Doug Lemov and his first two editions of Teach Like A Champion have had huge influence. But now he explains why he is rethinking his approach to behaviour advice…

Doug Lemov has been at the forefront of three education ideas that have sparked some of the most heated debates in the sector.

The first is “zero tolerance” or “no excuses” behaviour (usually termed by its supporters as “high expectations”). The second is the cognitive science approach to learning, involving a teacher-centred, knowledge-recall model. And the third is the charter schools movement in the US, which East Coaster Lemov played a big part in and which inspired academy trusts in England.

“It’s remarkable to think how much has changed in the past 20 years,” he says, shaking his head as we talk via video link across the Atlantic.

Lemov started as a school principal in Boston at the age of 28, before joining the State University of New York Charter Schools Institute, helping to set up charter schools that receive government funding, but operate independently of the state’s board of education.

He then moved to Uncommon Schools, a network of charter schools, and is still there 17 years later.

His best-known book, Teach Like a Champion, is a bible of pedagogy reform for many, while others accuse it of being too focused on uniformity.

One suspects Lemov would consider some of those who aren’t convinced as “sentimentalists”. In a new 3.0 version of the book he describes them as teachers who “mean well but love to be loved”, and who see being both demanding and caring of pupils as mutually exclusive.

Lemov feels English teachers have responded more than in his home nation. He was an adviser to Ark Schools and has worked with many more trusts since, while his “evidence-based strategies” have been integral to education reform in England, winning praise from former schools minister Nick Gibb.

“The charter school movement profoundly influenced trusts over here,” he says, but adds “the quality of schools and trusts that were founded in the UK” may have “actually surpassed the US”.

That’s because, he says, teachers in England are more responsible for and receptive to using cognitive science.

“I feel really optimistic for your country, and less so for mine.”

I feel really optimistic for your country, and less so for mine

But if many English educators and policymakers have enthusiastically embraced Lemov’s approaches, there are signs that some converts are reconsidering. More importantly, Lemov has been rethinking things too.

Take what’s happened across the pond. In 2004, Lemov joined Uncommon Schools, which runs 57 public schools across the northeast US, as its regional director for upstate New York. His area covered small post-industrial cities such as Rochester and Troy.

By 2011, a year after Teach Like a Champion 1.0 came out, he found himself pulled in two directions – improving schools in these isolated areas, or researching pedagogy and being a teacher-trainer. He chose pedagogy.

Since then, his team operates as a “kind of research and development” branch within Uncommon Schools.

Winding forward to August last year and Uncommon Schools published an open letter to parents, abandoning a core behaviour management method proposed in Teach Like a Champion 1.0, called SLANT (sit up, listen, ask and answer questions, nod your head and track the teacher).

“In response to feedback” from pupils and staff, it said the schools would “provide students with more flexibility in how they engage in learning in the classroom”, and would “remove undue focus on things like eye contact and seat posture”.

SLANT would be “eliminated”, it promised. The move split open the debate around behaviour management once again, with progressives claiming it as proof the traditionalist approach didn’t work. One blog in Schools Week said staff were now arguing “about whether Doug Lemov’s Teach Like a Champion is pragmatic or fascistic”.

And Katharine Birbalsingh, headteacher and now chair of the Social Mobility Commission, tweeted: “A titan in the world of education falls to progressive pressure. Uncommon, you have just let hundreds of thousands of children down.”

What happened?

Lemov sighs. He really wants to talk about brilliant teaching, not culture wars. “It is sometimes frustrating to me. In the 3.0 version, there are two chapters on managing behaviour and there are ten on everything else.”

But he answers graciously, admitting that SLANT has been misunderstood – and taking some responsibility.

“The first version of the book was almost too directive about what to do, that it caused people not to think enough about the why and how.

“Have I seen SLANT used badly? Yes, I have. If you know it’s about pro-social, non-verbal attention between students, teachers use it well as opposed to poorly.”

Have I seen SLANT used badly? Yes, I have

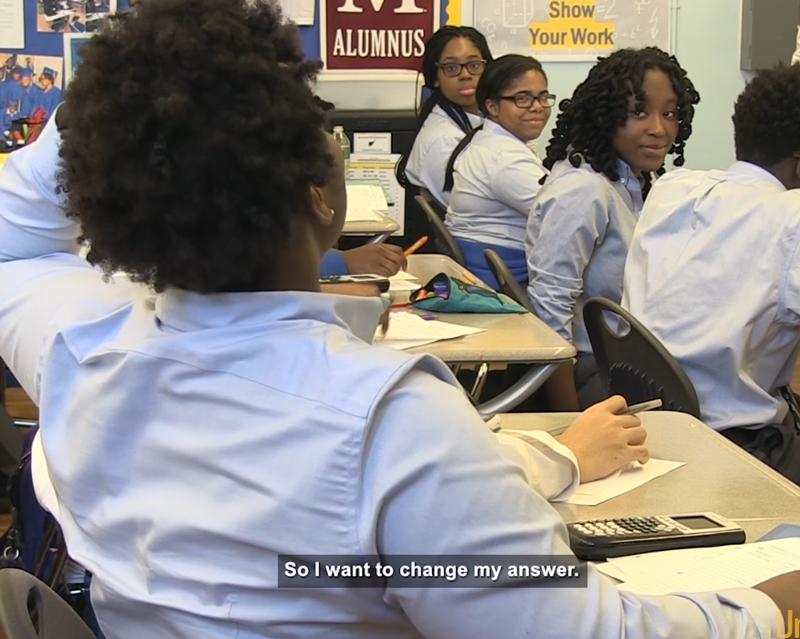

Lemov explains what he means by “pro-social, non-verbal attention” with a picture of some students. In it, a girl has started answering a maths question, but “made the hugely brave decision” to reconsider her answer halfway through, looking carefully at her three other students.

Lemov leans forward: this he really cares about.

“In a typical classroom when a student speaks, there is no working theory on what her classmates should be doing. So she has taken the risk to make the observation, and around her, she sees the body language of people slouched in chairs, looking away – their body language communicates extreme disinterest.”

Evolutionary science theory, Lemov says, tells us that humans are the only animals with big whites of their eyes, as to be a successful species we are hyper-alert to “the hidden drama of whether we are accepted into a group”. This drama plays out in classrooms all the time, he argues.

“Schools haven’t seen it as their role to shape the social environment in how pupils participate in class. Without realising it, our children spend their lives in environments that do not intentionally build cultures that value intellectual risk-taking.”

Schools do not build cultures that value intellectual risk-taking

But must students really have their arms folded and eyes fixed?

“There is nothing about arms being folded for SLANT,” he says. “It’s reasonable to tell students, place your hands on the desk, but that should be up to the discretion of teachers.

“Motivation is profoundly social, and people will tell you that the act of making that happen in classrooms is controlling black or brown bodies, or that it’s an act of violence. It’s engineering classrooms so they are loving, supportive and fully intellectual.”

So it must be frustrating that Uncommon Schools said it would be “putting greater focus on increasing intellectual student engagement”.

He says: “I do think SLANT was so focused on observable behaviours that it caused teachers to overfocus on that.” So in the book he has renamed SLANT “habits of attention”.

It’s still about “eye-tracking”, so no change there, and there is a new acronym: STAR – sit up, track the speaker, appreciate your classmates’ ideas, and rephrase the words of the person who spoke so they know you were listening.

This is to “emphasis purpose more clearly”, Lemov writes. (It’s worth noting Uncommon Schools says it is eliminating both SLANT and STAR.)

However, although Lemov is clearly doubtful about the open letter with Uncommon Schools’ proposals, he agrees he and the organisation “independently went through parallel processes” about rethinking their core behaviour strategies.

Does this mean a move away from zero tolerance and no excuses behaviour cultures is needed?

“There are a thousand steps a teacher should take before a situation reaches isolation, for example,” he says. “The best solution is prevention. It’s about not ending up in a situation where the best solution is something like isolation.”

The change also prompts the question whether some vulnerable students, such as those with special educational needs, have badly struggled in classrooms inspired by Lemov’s approach over the past ten years (not to mention whether the academy-local authority split has caused issues with support systems for them).

“With people with SEND, people underestimate the power of habits,” Lemov says. “If everyone is distracted from thinking, that’s important for all students, but it’s doubly important for SEND students. People look at predictability as boring, but it sets you free to focus on content. You can multiply that statement for pupils with special educational needs.”

Either way, Lemov cannot be accused of simply ignoring the debate. Rather than turning his back and showing the whites of his eyes, he has tried his best to sit up and listen.

I continually see proponents of these methods talking about how it “liberates the SEND pupils.” Ms Birbalsingh takes a similar stance as do others.

SEND students aren’t an amorphous blob – they have varying needs some of which are directly at odds with this edict e.g. the “tracking” edict is hard for some ASC students or those with ADHD/concentration and focus problems – for these students the effort involved in tracking would stop them being able to focus on the content of the lesson. Hypermobility often accompanies ASC/Dyspraxia diagnoses and “alert posture” again requires huge effort. Whilst these initiatives may improve “behaviour” for able-bodied, neuro-typical students – they are barriers to learning for others, especially those with hidden disabilities, and the ableism embedded in our school culture only serves to make it harder for so many pupils, including those with traumatic childhood experiences, which brings it’s own neurological challenges. There’s no nuance in a one-size fits all approach and where there’s no nuance, there will be those who suffer. Again.