Asiyah Ravat, one of Star Academies’ leading executive heads, tells Jess Staufenberg there’s no big secret behind one of the country’s best-performing schools – just relentless hard work

Asiyah Ravat is supposed to be on crutches. The executive principal at Eden Boys’ School in Birmingham fell off her bike in August, and as she strides across the school’s airy atrium, I can’t help feeling responsible for her precarious footwear.

“This is my first day back in heels,” she beams, pointing to her feet below an excellent fuchsia pink trouser suit. For a school leader responsible for some of the best progress results around, I feel we can’t possibly risk this woman keeling over.

The results have been covered widely already (The Economist even ran an article), but to recap: pre-pandemic in 2019, Eden Boys’ got the second-best progress scores in the country. It was beaten only by Tauheedul Islam Girls’ High School, under the same multi-academy trust, Star Academies, led by the enigmatic Hamid Patel.

As we sit down over chocolate cake (not a bribe for journalists – staff training session leftovers) I blurt out: but how do you do it? How do you get those results?

Ravat doesn’t miss a beat. “Great subject knowledge. You can almost, just by looking at a child’s frown, see the misconceptions they’ve got, and get rid of those.”

But how do you ensure your teachers have great subject knowledge? Teachers continue to train up one another, responds Ravat.

“So I look at the timetable, and if possible, I try to ensure all the teachers in the same department are free at the same time, and I give them a chunk of time when they can discuss pedagogy and subject knowledge,” she says.

For instance, science teachers with a specialism in chemistry (Ravat’s own background) covering all three sciences are trained up in physics by the physics specialist.

“It’s about how clear you are when you explain to a child. Questioning to check their understanding is key: how strong, how judicious, is your question?”

Strong teacher subject knowledge is then backed by set targets, she continues. “We intervene as soon as they arrive from primary school, and we set aspirational targets for each child.” All children take reading tests and, if needed, then receive group or one-to-one interventions. Pupils are also set by ability, across year groups and subjects, even art.

“I think both models can work, mixed ability too. But setting can work well as it can then be quite a competitive environment, and the teaching is targeted at that level. So in set 1 chemistry, I know they’re targeted at 7, 8 and 9.”

Is an 8 or 9 not achievable for children with poor key stage 2 results?

“What we’re saying is, if a child comes in at below national expectations, you cannot target them at grade 9. What we do is target all pupils a progress of 1.0 in every subject.” In other words, a pupil arriving at Eden Boys’ on track for a grade 5 will be stretched to at least a grade 6 – one grade above what’s expected.

It works. The latest data for Eden Boys’ shows a progress 8 score of 1.69, compared to the local authority average of 0.09, and in England of -0.03. Outcomes for special educational needs pupils are also strong.

Three very polite boys have now lined up outside the door (I wonder if they want cake, but apparently they’re here to show me around). They are bedecked in badges, including a ‘100%’ badge to indicate no school absence that term and a ‘Star Diploma’ badge showing achievement in community service, attainment and punctuality.

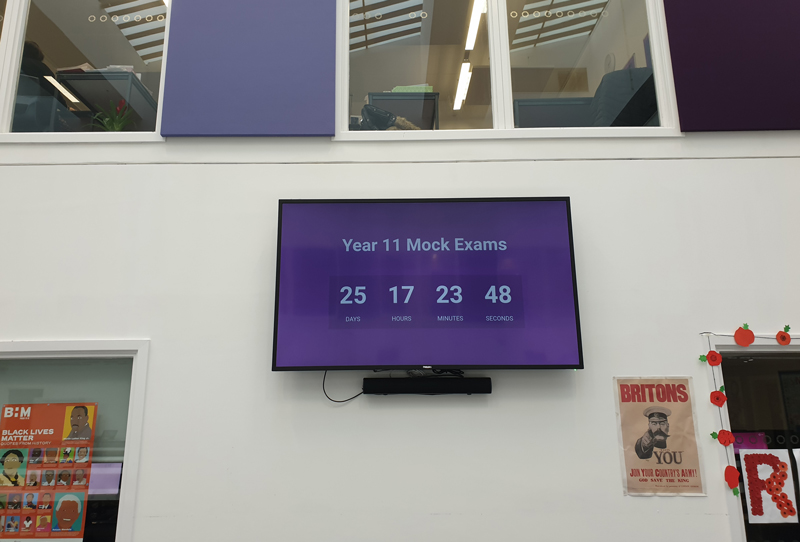

Back in the atrium, a big screen is beaming out the countdown to year 11 mock exams. “So we don’t forget,” smiles one of the boys. Parents are invited in to learn how to access mock exams online, and are walked through the exam timetable.

As we roam around, the boys tell me the single-sex set-up helps them “not to get distracted”. (Ravat later says it’s a response to parental demand.) Competition for places is very high, with 7.5 applications per place, despite the catchment area being a mere six streets. The pupil population is almost entirely Asian and Muslim, while 29 per cent are eligible for free school meals. Everyone seems very well behaved. All year groups have their own floor, to prevent lost time between lessons, says the head boy.

As I peer inside a science laboratory, the boys explain that if they are on target with grades, they can take some of their exams early in year 10, including two vocational subjects, such as graphic design or health/fitness, or a modern foreign language GCSE, such as Arabic. Ravat explains: “This helps make more time for English and maths in year 11,” amounting to two extra hours a week.

The inspiration for the school’s principles are also apparent, with hadiths (traditional Islamic sayings) on boards in corridors, such as: “Whoever guides another to do a good act will receive the same reward as its doer.”

Of course, the school shares many of the same communities as the Birmingham primary schools that experienced huge parental protests at teaching LGBT issues in 2019. I later ask Ravat if the protests affected her school. “Not at all. I think our parents understand that we teach relationships, health and sex education. We are very clear about that.”

She leans back, thinking. “What I’ve learnt is there is no real secret to successful schools: faith school, or non-faith school, it doesn’t really matter. It’s hard work and a relentless focus on improvement. It’s sweating the small stuff.

“We get pupils to focus on the little things. If they’re worried about making sure they have the right equipment or they’ve done their homework, they won’t get into bigger issues or poor behaviour. Sweating the small stuff is key.”

Much of this approach is the model across all Star Academies, explains Ravat, supported by staff workshops.

Ravat herself helped found three free schools at the trust, Eden Girls’ School Coventry in 2014, as well as Eden Boys’ and Eden Boys’ Leadership Academy, opening in 2015 and 2018 respectively. She also holds ‘executive principal’ title at two other trust schools.

They have all drawn significantly on her past experience, too. Ravat pioneered the effective use of data in previous schools: as deputy head at Waverley School in Birmingham she took results from eight per cent A* to C in science GCSE to 84 per cent. Similarly at Park View School, also in Birmingham, she took science results into the top one per cent nationally, winding up on Teachers TV (which used to be a thing).

“I introduced using data to track pupils’ performance, and pupil-level data to identify what the actual barriers were for each child,” she explains.

Like many children of immigrant parents, Ravat attributes her success to unfailingly high expectations from her Gujarati parents at home. Her dad had a kebab van, and one of Ravat’s early memories is peeling potatoes for chips at the weekends. For him, education was paramount.

“My dad had great aspirations for us. Every day he would ask us after school, what we’d done at school, did we need support, did we need more textbooks? We were all told, ‘I don’t want to receive a call from school saying you haven’t done your homework’.”

Ravat thinks she might even be the first Indian Muslim girl in Walsall (the town near Birmingham where she grew up) to go to university. “I got my first in chemistry at university because of my dad,” she smiles.

After her degree at Queen Mary University in London, she worked briefly as a chemical analyst while also tutoring. Finding her tutoring students got good grades, she turned to a PGCE in Birmingham.

The aspirational immigrant culture that Ravat benefited from in her childhood home may also benefit many of her students now. Pupils with English as an additional language make better progress than their peers on average, data shows (47 per cent of Eden Boys’ are EAL pupils). Schools with top progress scores are often also single-sex and faith schools.

But Ravat warns against a simplistic interpretation of her pupil cohort. “We serve a very, very deprived community. We deal with behaviour issues, there are gangs in the community, there’s a knife culture.” The idea that most students are arriving from highly aspirational backgrounds is “not true at all”, she says.

The additional language can be as much of a hindrance as a help, she adds – some parents have refused to come into school because they can’t speak English, for instance. “It’s simply our approach. It’s personalised support for each child, with high-quality teaching and interventions.”

Given her track record in hugely boosting children’s grades throughout her career, Ravat clearly has an approach that works. As I leave, she jokes she spent two days after her fall walking around on broken bones without realising.

Watching her stride purposefully back into her school, I can really believe it.

Your thoughts