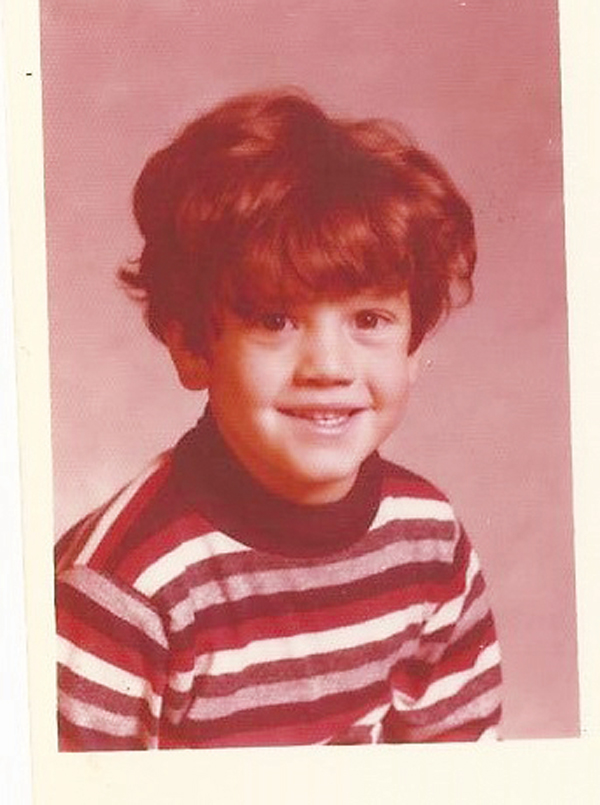

Doug Lemov had a “pretty miserable” time in his early teens. “I was kind of the ugly duckling. To add to that, I would say I was… socially awkward, and eager to not be.”

To fit in, he says, he wanted to be seen as someone who didn’t really care about school. “That was cool. So I was reading what the environment demanded of me and it meant relatively self-destructive behaviours. I tried to never carry books or paper or pencils to class. It can’t have fooled anyone.”

He observed school, rather than took part in it, he says, looking at ways to challenge the culture and what teachers were trying to achieve. But those years stemmed his interest in schooling.

Talking by Skype from his home three hours north of New York, the author of Teach Like a Champion believes there is not enough talk about the reality of teaching “and how difficult it is, especially with the least privileged kids”.

Born in Washington DC in 1967, in the “heyday of the hippy movement”, his interest in social policy can perhaps be traced back to the dinner table conversations his parents had with him and his older sister Becky.

“I felt that was, you know… my dad reading the paper to me, and talking to me about arcane points of social policies… one of my most intense, perhaps not fondest, memories of youth.”

The family left the city for the suburbs when Lemov was a child, after his father was held up at gunpoint. This is said so matter-of-factly it takes me a moment to realise the significance of what he has said.

He just says it is a “very American experience”. That’s not to say he doesn’t note its gravitas, but just that society is different across the pond. “Poverty can be a life and death struggle very quickly.”

Lemov talks of how one of the big things he noticed on a family trip to London was the “lack of guns”. That, and that children and the Central line at 8.30am do not mix. “It’s very stressful… your children could be swept out of your hands like some kind of river, it’s pretty insane.”

And just like that, he moves on.

Given his standing now, it is hard to imagine the boy he describes as an “unremarkable student”.

It was his sister, who is two years older, who was the “superstar” – “always got straight As, held the school record in the 1,000m run, a brilliant artist” – before she headed to Ivy League college Yale

Did this make him rebel? In a way. The schools of the late 1970s and early 1980s accepted a “pecking order” culture among children, creating a Lord of the Flies-type environment, he says. He didn’t think he was bottom of this barrel, but acted in a way so as not to befall that.

“I’m sure it was painfully clear to everyone I was some kind of faux-intellectual type. I listened to art rock and all the kinds of things young intellectuals would listen to. But I wanted to be seen as someone who didn’t really care about school. I think it was mostly a failing of the person I was in high school that I didn’t have the confidence to be who I am. But the culture in schools didn’t help.

“There was this narrative that part of what you need in life to be successful is to be a social person, and that was more important than academics. So the message was if you’re having trouble getting on with your peers, you should really work a lot harder to be more socially accepted.”

“There is no formula for teaching”

He tells the differing stories of two teachers’ reactions to him aiming an elastic band at a classmate (he had no intention of firing it). One would be aware of what he was attempting to do and stop him, sometimes just with a look, which would make young Lemov, the teacher, and the target, happy; another was oblivious and he would be goaded into making a decision – fire the elastic band, or not and lose his “cool”?

Behaviour, then, is something that has been on his mind for a long time.

Teach Like a Champion has just two chapters about behaviour management, but it’s what people talk about the most.

“Both the detractors and the people who like my work spend more time talking about the behaviour chapters than any other – I think it suggests how huge an issue it is in schools and classrooms, and there are so few solutions.

“It’s painful, physically and emotionally, to be put in charge of a group of 30 youths, and to struggle, not only to teach them as much history or science or English as you need, but to be able to get the classroom to work.”

He doesn’t want teachers to feel like failures, he says.

People have accused him of turning teachers into robots, but this is something he rebuts.

“There is no formula for teaching – the tools every teacher uses are different, and they adapt them differently. That’s one of the beautiful things about the profession.”

His career in teaching started straight after college as a “debt of gratitude” to his professors, leading him to work as an English teacher at a New Jersey independent school.

Not long afterwards, he decided he wanted to be a professor of literature, and applied to a PhD programme at Indiana University. But it didn’t take him long to realise it wasn’t for him. “I was part of this educational system that was this great, giant ship that didn’t do the things it said it was set out to do.”

So he left with a masters, leading him on his current path.

“I wanted to be a part of education, but I knew I wasn’t the kind of person who would spend their lives working away in the bowels of a machine that didn’t work. I wanted to be a part of an organisation I believed in.”

In 1997, he became a co-founder of the Academy of the Pacific Rim Charter School, the American version of a free school. He was appointed dean of students and therefore took the lead on behavioural issues. “No one else was foolish enough to do that,” he laughs.

Shortly after opening the school, Lemov became the school’s principal at the age of just 28.

“That was a scary day. As was the next when I found out the business manager was behind on paying into the retirement fund, which was huge.”

He then gathered a “great group of people” and the school became one of the best-performing in Boston, an early example of successful charter schools.

Marriage and children came soon after. Lemov has been married for 16 years and has a 14-year-old son, and two daughters, aged 12 and 7.

With a growing family, he took a step back from his role at the school and began working on the system by which charter schools would be evaluated and assessed in New York state, as well as then studying for his MBA at Harvard Business School.

“I was the oldest person in my business school class, and I had a reminder on my Microsoft outlook calendar on the first of every month that said DROP OUT. But I never did.”

Lemov believes the teaching at Harvard changed his own style, and has influenced many of his techniques, including the “cold calling” described in his book, although he admits that he adapted it heavily.

“A lot of people have a very stereotypical notion of what cold calling at business school is like and it’s not really what I suggest teachers do in primary and secondary classrooms.”

He is now one of the managing directors of Uncommon Schools. But his most important job is to his family.

“I want to be the best dad I can be, so that’s meant strategically demoting myself and saying no to things I really want to do.

“I mean, if no one had ever bought a copy of Teach Like a Champion, or if all people had done was scream at me about how ‘evil’ my book was, I would be so grateful to have spent so much time watching brilliant people teach and inspire kids and get the best out of them. It’s totally changed the way that I parent. I will be so eternally grateful.”

HOW DO YOU WORK?

What is your daily routine?

I have my day job and on top of that have lots of writing that I need to get done. Plus, I have three children. All of that tends to mean that I get up early to write or to exercise. Luckily I am a morning person. One small routine is that I try to be very attentive to my first interaction with my kids. I want them to know: you walking in the room makes me smile. I also read to my children a lot.

What’s been your worst professional moment?

I am just about atop the league tables in mistakes, sometimes catastrophic and often public. But I have learnt not to hide errors; to have the

humility to admit when I am struggling. When in doubt trust your colleagues and ask for help. So many times I have seen someone make a mistake and compound it a hundred times by trying to cover for it.

Of the jobs you have done in the past, which was your favourite and why?

I love my job now. It’s such a gift to get to study and write about great teachers and what they do. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

What professional skill have you had to develop?

I am an introvert. But at work I have to get up in front of large groups for days at a time. Plus I am often asked to appear as an expert when that is not what I feel inside. So I practise a lot to make myself relatively comfortable speaking to groups.

Your thoughts