Ofsted has published its annual report for 2021-22, the first academic year in which inspections were mostly unaffected by Covid since 2019.

But chief inspector Amanda Spielman warned today of the “shadow cast by the pandemic over education”, adding that education recovery is “far from complete”, with problems exacerbated by a “workforce crisis” in education.

Here’s what we learned…

1. Two thirds of schools not graded in five years

Ofsted said it was “concerned” 64 per cent of schools had not had a graded inspection in the last five academic years, and 14 per cent had not had one in 10 years.

This is due to most inspections of ‘good’ schools since 2015 have been ungraded, and because ‘outstanding’ schools were previously exempt from inspection completely. It is also due in part to the pandemic.

The government recently lifted the inspection exemption for ‘outstanding’ schools, leading to four in five losing the top grade.

Ofsted said some ‘outstanding’ schools were “excelling”, but “others have fallen behind”.

This included some that had “relied on strong performance data to achieve an outstanding judgement”, but had not “demonstrated the necessary substance and integrity” under scrutiny of the new inspection framework.

2. ‘RI’ and ‘inadequate’ schools more likely to improve

But the picture is not all doom and gloom. Seventy per cent of previously ‘requires improvement’ schools inspected last year improved to ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’, up from 56 per cent in 2019-20.

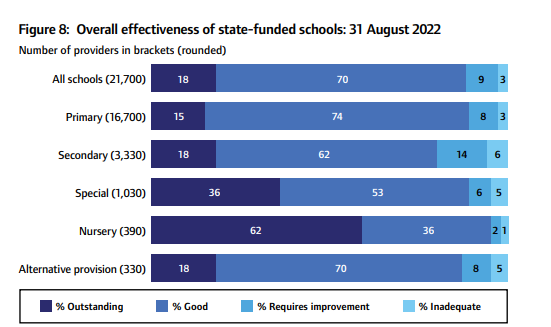

Overall, 88 per cent of state schools were judged ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ at their most recent inspection, up from 86 per cent in 2021.

Of 220 schools that were previously ‘inadequate’, two per cent became ‘outstanding’ and 63 per cent became ‘good’, while 29 per cent went up to ‘requires improvement’.

Ofsted said it was “encouraging” to see just 5 per cent remained at the bottom grade, compared to 8 per cent in 2019-20.

3. Part-time timetables used as ‘alternative’ to exclusion

Spielman warned the pandemic had “obscured trends” in exclusions and off-rolling, so it is harder to tell if off-rolling is still a problem.

But she said there was “anecdotal evidence that part-time timetables are being used more regularly in schools”.

“This is where children attend school, but their attendance is limited to a handful of lessons. This might be held up as an alternative to exclusion, but it is another avenue by which children can slowly slide out of education.”

Ofsted reviewed school census data from January 2020 and 2021 to look for off-rolling.

It found 160 schools had “exceptional levels of pupil movement”, compared with 320 in 2020.

However, Ofsted said because 2020 and 2021 performance data was not used for accountability, it “may mean that schools have had less incentive to off-roll pupils”.

4. More MAT evaluation ‘events’ planned

Multi-academy trusts cannot be inspected directly. Instead, Ofsted carries out “summary evaluations” based on batch visits to several schools in the same chain.

Ofsted conducted five evaluations last year, finding “broadly positive” insights. However, they found some “areas for improvement, including for trusts to collaborate more with other trusts”.

The watchdog said it would continue to develop its programme of MAT evaluations, with some other “MAT events” which are similar to summary evaluations but with “slightly different themes”, and covering “more sizes and types of MATs”.

Ofsted plans to complete 12 of these “events” this year, to “improve our methodology and understanding of the MAT sector”.

However, Ofsted also repeated calls for the power to inspect MATs directly.

5. Insufficient powers over ‘chaotic’ and ‘unsafe’ illegal schools

A taskforce set up in 2016 to tackle illegal schools has so far investigated just under 960 unregistered settings in England, inspecting around 660 and issuing almost 160 warning notices.

Investigations found children in “chaotic institutions where disorganised managers and staff fail to provide a proper education”.

Some children are in unregistered schools “where they are exposed to misogynistic, homophobic and extremist materials that are contrary to British values”.

Ofsted has also found unregistered schools “operating in unsafe and inappropriate premises”.

It identified serious safeguarding concerns in “more than a quarter of the unregistered schools we inspected, which have put children as young as five at risk”.

However, the watchdog has only brought six successful prosecutions because of its “limited powers”. The schools bill, which proposed greater powers, was recently scrapped.

Spielman said today Ofsted was “disappointed that the schools bill won’t progress”, but said they had been “reassured that the education secretary remains committed” to the proposals around illegal schools.

6. ‘Concerning’ placement rise in unregistered AP

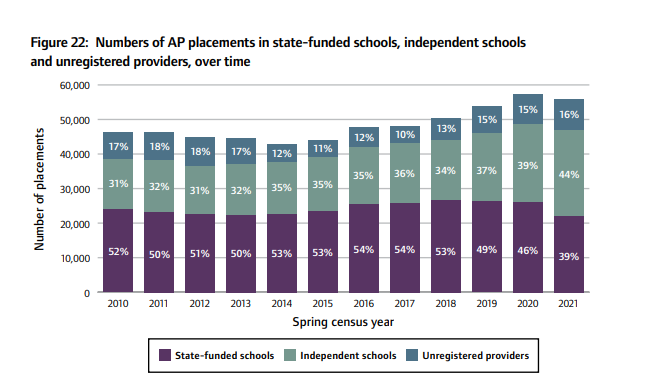

Placements in registered state-funded alternative provision fell by 16 per cent to 22,000 between January 2020 and January 2021. But the number of placements in independent schools and unregistered providers continue to rise.

Ofsted said the rise in unregistered AP was “concerning, given that they operate without oversight” and pupils are more likely to be exposed to safeguarding risks.

Over half of Ofsted’s unregistered school inspections were of AP providers last year, up from a third in 2016. AP accounted for seven out of 10 warning notices.

Some schools commission AP placements “without checking suitability or legality and safeguarding arrangements”, but after concerns were raised the schools “improved their approach” to commissioning. AP schools were also less likely to be ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’.

Ofsted said “wholesale change” is needed to make sure “thousands of, often vulnerable, children get the high quality education they need and deserve”. The watchdog called for “compulsory registration for all AP”.

7. ‘Significant weaknesses’ in SEND system

Ofsted has criticised the SEND system, saying it has “signficant weaknesses”.

Families experience “significant delays and difficulties accessing support” and have “frustrating and adversarial experiences” which were exacerbated during the pandemic.

But they say a lack of high-quality education, health and care services could have resulted in some children being “mistakenly identified” as having SEND.

Ofsted is also “extremely concerned” that over two-thirds of council areas have “significant weaknesses” in SEND.

8. Rise in independent special schools

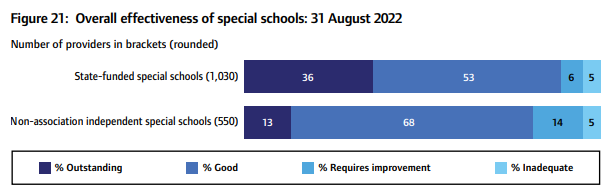

The number of – sometimes costly – independent special schools has continued to grow from around 520 in August 2020 to 620 currently, the report says.

Schools Week has reported on the millions council spend on these schools, as mainstream special schools are “bursting at the seams”.

Ofsted said the proportion of non-association independent special schools judged ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ has declined slightly from 84 per cent last year to 81 per cent.

In mainstream special schools, 89 per cent were rated as the two top grades, similar to 90 per cent last year.

9. Some teacher trainers ‘bolt on’ core content framework

The watchdog said it had also identified “weaker ITE curriculums”, with some providers not having fully implemented the government’s new core content framework.

Some of these weaker providers “treat the core content framework as a ‘bolt-on’, adding key principles in an ad hoc way, with little thought to how they build trainees’ knowledge or practice”, Ofsted said.

“Also problematic are providers that rely too heavily on the core content framework, treating it as a generic curriculum model, with little attention to the specific subject expertise trainees will need.”

10. ‘Difficulty’ finding teacher training placements

Ofsted found during its inspections of initial teacher training that some providers had “difficulty finding school placements”.

This was for a “number of reasons”, including pressure from the pandemic on schools making some “less willing to host trainee teachers”.

“Equally, high-quality mentors now have to divide their time between supporting early career teachers on the ECF programme and trainee teachers.”

These increased expectations and competing demands have “exacerbated previous placement shortages”.

11. ECF creates teacher and mentor workload woes

Ofsted found many participants in the early career framework, which provides two years of induction for new teachers, and national professional qualifications for more experienced staff, were “happy with their training and believe it is helping them to improve in their roles”.

However, “some early career teachers find it difficult to complete the training alongside their school responsibilities”.

Schools are “concerned about the workload that the ECF programme creates for early career teachers and mentors”.

Your thoughts