The shadow children’s minister hails from a political dynasty – and met Mandela and Mother Teresa when she was a child. Tulip Siddiq tells Jess Staufenberg of her impatience to get into power

Tulip Siddiq is practically engulfed by her sofa. At 4ft 11in, the shadow children’s minister is small in stature but perhaps it’s exactly this – as well as being the middle child – that means she talks with force and volume, like a powerhouse.

Siddiq stares hard and long while you ask a question, and then responds with a forthrightness and candour one wouldn’t expect from someone who has spent their whole life in politics, navigating council cabinets as well as Westminster.

If shadow education secretary Kate Green’s strength is in spotting “stupid policy”, then Siddiq is who you would want to go and tell the person in charge why it’s so stupid.

The look on her face in such an encounter would, I expect, be similar to her deeply unimpressed and distressed expression in 2019 when she made national headlines for having to postpone her caesarean to attend a key Brexit deal vote. Parliament’s arcane processes wouldn’t allow Siddiq a proxy vote, despite being heavily pregnant. There’s a picture of her sat in a wheelchair in the House with colleague Clive Lewis standing protectively at the handles – an image you could imagine in future politics textbooks on parliamentary reform.

But we’re not here to talk about Siddiq’s children, rather the nation’s children, policy for whom she would be responsible if Labour come to power. The brief covers everything from high-needs funding to special educational needs, children’s mental health and free school meals – the latter of which has exploded into the public eye during the pandemic.

“Every time I asked the prime minister, he would keep saying, ‘no child will go hungry in this pandemic’,” says Siddiq in disbelief. “And I would just look at him thinking, I mean, which world is he living in? It’s just divorced from reality. Because if he looks at the statistics…”

Siddiq did so and says she found Johnson’s constituency – Uxbridge and South Ruislip – has more children on free school meals than Siddiq’s own, Hampstead and Kilburn. She was part of a group who sent the findings around parliament to “try to shame the Conservatives into voting” for free school meals in the holidays, she tells me, reeling off the stats. Almost two million children have been in households short on food during the pandemic. About 200,000 children were skipping meals during the first lockdown. “It’s 2021, this is the UK, and children are skipping meals,” says Siddiq with contempt.

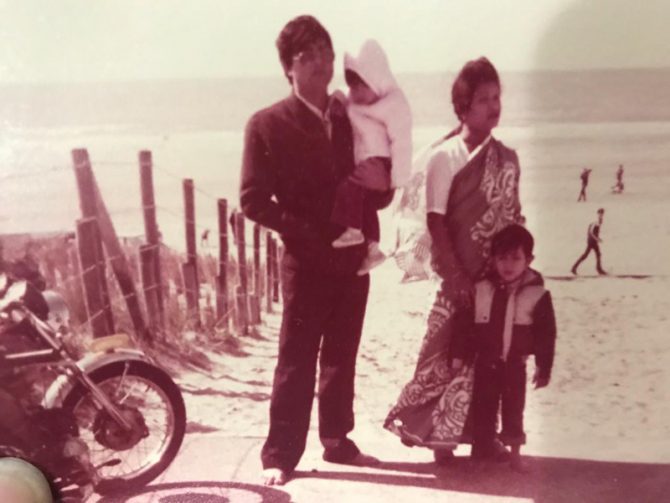

Fighting for a cause is in Siddiq’s DNA. Her mother arrived in the 1970s as a political asylum seeker in the very constituency she now represents, after 19 members of the family had been killed in Bangladesh. Her mum only escaped because she was in Germany.

“She was on holiday and she was literally told her world had turned upside down. You can imagine her association with politics was not positive after that.”

Her mother’s family is part of a leading political dynasty in Bangladesh: her aunt, Sheikh Hasina, is the country’s prime minister and was the leader of the opposition during Siddiq’s childhood, while her grandfather, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, had been the country’s first president and was later assassinated. When Siddiq was nine years old her father, a university professor, moved the family back to Bangladesh for a few years. It made for some unusual moments during a childhood otherwise filled with cricket and homework.

“Nelson Mandela came to Bangladesh and I was invited to meet him! It was like meeting someone who wasn’t human,” says Siddiq, eyes widening. “You just stand there looking at this towering figure. I couldn’t believe he was there.”

The young Siddiq also met Mother Teresa, whose work just over the border in Kolkata was world famous. “It was a bit like meeting an angel.”

But it wasn’t these otherworldly figures who inspired her into politics. Her family moved to Bangladesh’s warmer climate to help her father recover from a huge stroke. “The NHS saved my father’s life. It’s why I joined the Labour Party,” says Siddiq. Aged 16, she told her dismayed mother she would be entering politics, following her relatives before her.

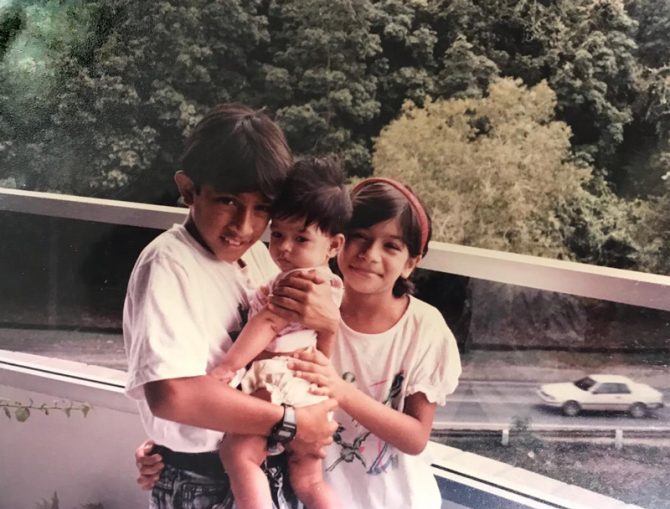

Siddiq’s parents were also key influences. She laughs as she describes her mother ruling “with an iron fist”, setting disciplinary standards Siddiq says she can’t possibly maintain with her own two young children. “The emphasis on education was intense. My parents were always breathing down our necks at every opportunity about grades – there was a lot of pressure.” It seems to have worked: her brother works for the United Nations and her sister for the Children’s Society. It’s also why Siddiq is not one to be drowned out. “I’ve got an older brother and a younger sister! That’s why I wanted attention. Why I’m shouting all the time.”

That determination got Siddiq into positions of responsibility early in her career. Aged just 22 she was working for Philip Gould, a key architect of New Labour. “It was really high-paced, very intensive, and you realise then that you either like the world of politics or you don’t,” explains Siddiq. “It was very exciting – the transition of Blair to Brown. I got to listen to that conversation.”

By her mid-20s she was a cabinet member on Camden Council responsible for a £22 million budget. It’s also where she learnt to hold her own. Turning up to meetings were Labour Party peer Joan Bakewell, “Ed Miliband’s mum”, presenter Victoria Coren Mitchell and “that guy from Only Fools and Horses”. With such high-profile locals, Siddiq learnt early: “You can’t just make a decision and hide from the public.”

It’s why the government’s denial over their actions during the pandemic infuriates her.

Siddiq praises her opposite number Vicky Ford for “always keeping the door open” to her. But she is critical that Ford and so many other Conservative MPs have “toed the party line”, including voting down extending free school meals in October last year. “Loads of Conservative MPs came up to me, whispering in corridors, saying ‘oh we really don’t want to’,” she says.

Siddiq can at least speak from a position of consistency: she resigned from her current role in 2017 over Jeremy Corbyn’s order to vote for triggering article 50, before being reappointed by Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer last year. “The government have been shamed into action last-minute” on child poverty time and again, she grimaces.

Why do we even need free school meals in a country like this? It’s a sticking plaster.

As children’s minister, child poverty would be her focus. Then, with increased force, she adds: “Why do we even need free school meals in a country like this? It’s a sticking plaster. In an ideal world we’d be in a situation where no one needs free school meals.” Her other focus would be ensuring there is “coordinated action” on mental health services for children, after a decade of funding cuts have decimated Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

Siddiq would have the advantage of being able to keep her ear to the ground. Her husband is an education consultant and formerly a governor at Swiss Cottage School, a leading special needs school in Camden. She herself is a governor at nearby Emmanuel C of E primary school. “All the cabinet ministers, they’re all constituency MPs at the end of the day. They must realise there is a need for a new package of social security reforms,” Siddiq shakes her head. “Or are they just overlooking it?” She’s finished with criticising, she says. “I’d like us to be in government now. I’m done with chuntering from a sedentary position.”

Your thoughts