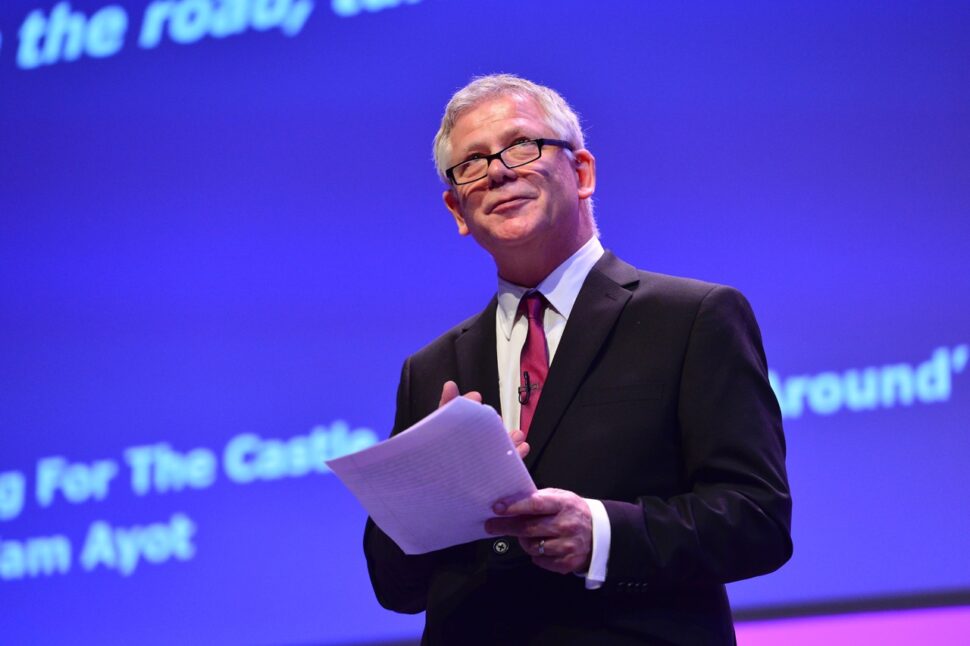

Steve Munby talks to Jess Staufenberg about why he left the National College for School Leadership and whether we really have a ‘self-improving system’

Talking to Steve Munby is a bit like talking to an embodied, institutional memory of the schools system in England. In 2019 he was as relevant as ever, publishing an education book on leadership to general rave reviews; but he can also quite clearly remember life without Ofsted and GCSEs.

Several times in our conversation he grins broadly, announcing that one or the other of us is “showing our age”, as he mentions things he remembers from the 1970s and 80s that I’ve never even heard of. It gives him an unusually fascinating perspective on where we are now.

It’s been an extraordinary career arc for Munby: from his childhood in Newcastle, he followed his social worker father into the public sector and became a secondary school teacher in Birmingham and Gateshead from 1978 to 1985.

After seven years in the classroom, he left to advise various local authorities across the north, and from there took on the huge role of chief executive at the National College for School Leadership. These days, he is an education consultant and visiting professor at the Institute of Education, UCL, in London.

But it all began rather more inauspiciously.

School standards in the 1970s were low and teachers were barely held to account, says Munby. “I didn’t even know the exam results for my own subject, because no one did.” The existing inspectorate turned up “every ten years” and “it was possible to be pretty mediocre as a teacher and keep your job”.

Munby self-effacingly calls himself a case in point. “I was basically too nice – I just didn’t know how to manage behaviour.”

There being no formal appraisals of teachers, Munby has only ever found evidence of his performance from those days on the website Friends Reunited. He says it reads: “Does anyone remember Mr Munby? He wore a beard and drove a yellow Ford Cortina. He was a nice man but he couldn’t control us. It was a wonder we learnt anything.”

Munby chuckles. “Schools are much, much better now.”

After teaching history and English in Gateshead, he got a job as an ‘advisory teacher’ to Sunderland City Council, to deliver the Technical and Vocational Education Initiative (known as TVEI).

Brought in by Margaret Thatcher and then-education secretary Keith Joseph in 1983, the idea was for 14- to 18-year-olds to build up a record of achievement including technical and social skills, outdoor activities and employer links. It’s the kind of broader capture of achievement that school leaders are looking at now post-pandemic.

Munby himself was especially interested in “involving students more in assessment and reflecting on their learning. It was the forerunner of ‘assessment for learning’. In the end, there was too much emphasis on the formal record of achievement. But there was some great work going on with formative assessment.”

He thinks much of that broader approach has been lost (TVEI was scrapped in 1997). “It’s not that I think examinations are wrong, but we’re failing to recognise the broader aspects that young people bring. The system is very narrow, and much narrower than it was.”

The system is very narrow, and much narrower than it was

Following Sunderland, Munby spent two years as an assessment consultant for schools across the north-east, before landing a job as an adviser to Oldham local authority in 1989, just as GCSEs were replacing CSEs and O-levels. Ofsted came along in 1992, and performance tables were also introduced.

“It was a huge time, because everything suddenly changed,” says Munby. But back then, some SATs were assessed by teachers. “That helped teachers to understand what good looked like,” he says. “The system at the moment encourages a dependency on examination, rather than robust moderation of teachers’ judgments.”

After a stint as assistant director of school improvement at Blackburn Council, Munby then became director of education at Knowsley Council in 2000, which he calls a “key moment” for him.

Knowsley had the second-worst GCSE results in the country, and some serious issues. Munby remembers getting a phone call from one headteacher being threatened by a parent who was a dangerous local gangster and having to frantically ring around the police department.

But after one year, Knowsley had dropped to the worst GCSE results – and the Liverpool Echo published a letter calling for his resignation. “That was a dark night of the soul,” grimaces Munby.

Determined, he brought all the Knowsley headteachers into one room and set new goals. Munby says Knowsley became one of the most improved local authorities, and GCSE results moved from the bottom to the eighth lowest.

Not long after, he was asked to apply for the huge job of chief executive of the National College for School Leadership, which opened in 2002. The college had a striking centre in Nottingham and was dubbed the “Sandhurst for schools”.

“It shocked me, as I’d never been a headteacher,” says Munby. It surprised then-education secretary Charles Clarke too, who asked Munby’s interviewers (Michael Barber, a chief adviser, and Peter Housden, director general for schools), to reconsider. “They still recommended me!”

He wanted to make the national college “less insular” and so at a conference in Birmingham he pledged to “telephone 500 headteachers in the first three months of the job”. Somehow he managed it. “It was a crazy promise, but it was one of the most important things I did.” In the ensuing years, his team helped roll out the National Professional Qualification for Headship and other leadership development programmes.

I telephoned 500 headteachers in three months

But in 2010 the government changed. Munby found himself waiting anxiously in the wings at yet another national college conference, to give a speech on “servant leadership” following the Conservative Party’s pledge for a “bonfire of quangos”.

“That’s the most important speech I ever made,” he says. Gove was sitting in the audience, and Munby had no idea if he was “going to close us down or not”.

Then it was Gove’s turn to speak. “He said, ‘I’ve come to say, “Hail Caesar!”’” He praised the national college, and it continued its work. However, by 2013, it was merged with the Teaching Agency, and eventually closed down in 2018.

Munby thinks that moving the NCTL from a non-departmental body to an executive DfE agency in 2012 changed how it was perceived, and he did not enjoy suddenly becoming a civil servant. “When it became part of the department, it lost something. It was hard for us to be seen as halfway between schools and government.”

He also now “had less influence”, adding, “I didn’t enjoy the culture in DfE. For me, it seemed about having meetings all day and not getting anything done.” After eight months, he left to become chief executive of the Centre for British Teachers, which he renamed the Education Development Trust, bidding for contracts to run school improvement programmes all around the world.

More recently, Munby has become even better known, with his book Imperfect Leadership, published in 2019 (he has a follow-up out soon). To generally rave reviews, it expounds the idea that all leaders need mentors and should ask for help.

“Hero heads are now much less in the limelight, and there’s more talk about system improvement, and I think that’s a healthy change,” reflects Munby. He adds he would rather we had ‘national support schools’ than ‘national leaders of education’ – placing emphasis on the team, not the individual.

But system improvement is also more centralised now, he notes. “I’m not bitter about the college closing – that’s politics. But what you’ve got now is a market. So instead of the national college being the vehicle by which to help schools, the department puts out a contract and people like the Ambition Institute or Teach First bid for this work.”

He pauses. “You could argue it’s a more self-improving system. But I think interestingly the system is also now more centralised. What needs to be done is now laid down quite a lot. There’s been a centralisation of control of standards.”

With research out in September showing two in five headteachers are planning early retirement, Munby’s long historical view of school system leadership is especially valuable. Perhaps ministers could trust more in the ‘imperfect leaders’ he celebrates, and release a little more control back to them.

Your thoughts