Deafness shot into the national consciousness recently with a deaf contestant on Strictly Come Dancing. But award-winning teacher Matt Jenkins shows Jess Staufenberg how many assumptions still need unpicking

Clear messaging during the pandemic has not been, by anyone’s standards, a strong point of the UK government.

The proliferation of jargon alone was confusing: PPE, superspreaders, key workers, tiers 1, 2, 3, contact tracing, lateral flows, PCR, herd immunity, SARS-Cov2 and my personal favourite, “flattening the curve”.

Then the ever-changing rules: mixing households, hugging or elbow bumping, drinking but only with a “substantial meal”, and so on. As a hearing person, I could have benefited from an instructions manual.

Now imagine that your language is visual, not verbal, because you are deaf. Then imagine the government doesn’t include a British sign language (BSL) interpreter during its Covid announcements, for months on end.

It seems like a colossal oversight, especially given the national support last year for Strictly Come Dancing star and deaf contestant Rose Ayling-Ellis.

“There was no information – we were like second-class citizens, and for the children, it was even worse,” says Matt Jenkins, a lead BSL and deaf studies teacher at the Deaf Academy in Exmouth.

“Historically, we’ve always had to battle for information. With Covid there was all this new language coming out, but no interpretations.”

There was all this new language coming out, but no interpretations

In November, Jenkins won the ‘lockdown hero award for learner and community support’ at the Pearson teaching awards, alongside his colleague, Jo Fison.

I’ve travelled about five hours to visit his school in Devon, a non-maintained specialist provision with a long history and currently 58 students on roll, aged between seven and 22, including residential placements.

When Covid hit, the school’s new state-of-the-art site wasn’t finished because of delayed building materials. The school’s old site had already been bought – meaning students were stuck at home, surrounded by a pandemic not being explained to them in their language.

So Jenkins set up his ‘Ask a Deaf Teacher’ YouTube channel, and families were invited into Zoom sessions. He and staff also sent home “exciting parcels” with activities for students, such as building boats and taking photographs.

“We had to make sure that as the language around the pandemic evolved, they could understand it. It was a lovely informal environment. I really appreciated that time together.”

Jenkins is talking to me through BSL, which is being translated at lightning speed by Vanessa Larkin, a translator at the academy.

It means they are looking at each other, in order to communicate, and I look at Jenkins, trying to match what he’s saying to the words Larkin is pouring out at my side. It is the most extraordinary crash-course in what language is and does.

Jenkins’ award only scratches the surface of what makes him a tour-de-force educator. With endless explanations and re-wordings to ensure my comprehension, he explains more to me about deafness in two hours than I’ve ever learnt in three decades.

First off, students are on a “deaf spectrum”. We walk around the school, so he can show me what he means. Some will arrive fluent in BSL (such as those, like Jenkins, who grew up with deaf parents – but this only accounts for five per cent of deaf children. The rest grow up to hearing parents).

Others will have grown up with “oralism”, which means communication through lip-reading and speech. Many are bilingual in both languages, and the school must cater for that.

So for instance, windows to the outside world are small and high, Jenkins explains, because if the sun is in someone’s eye they will struggle to see people talking to them.

Absorbent soundboards in classrooms prevent distracting echoes from interfering with sensitive hearing technology.

Beside the whiteboard is a “traffic light” system of red, yellow and green lights, so all students can see when the noise in the room is getting high, and possibly distracting.

There are windows on the inside walls of classrooms too, so people in corridors can eavesdrop without having to enter the room. When someone does want to enter, a light flashes, meaning door knocks aren’t needed.

The school is an environment in which deafness is factored in, rather than ignored. In other words, the language of the deaf community is properly possible here. Jenkins then says something which turns my assumption about deafness on its head.

“What you have to remember is that society created our disability for us and for our students,” says Jenkins. “We are a language minority, that’s all.”

Students often arrive at the school “confused about their deaf identity, and not aware of deaf culture”, he continues. I have to interrupt: what is deaf culture? Jenkins smiles.

Students often arrive at the school confused about their deaf identity

“Interrupting, for example,” he laughs – deaf people say what they mean and are often blunter than an oral person speaking English (I remind him that I’m half-German and so it would probably go down a storm over there).

“There’s also a really visual humour, which needs lots of space,” says Jenkins, leaping up to tell a joke with great exaggeration. “That’s why the corridors are so wide here, so you don’t end up hitting someone.” This is a very physical, expressive, 3D culture.

And what about deaf identity? “It’s a bit like LGBTQ+, where a young person is asking, am I straight, am I gay? So they’re coming here and looking around and asking, am I hearing, am I deaf?”

This can be known as “big D deaf” or “little d deaf”, Jenkins continues. “Big D deaf is where you’re really like, ‘I’m deaf!’.” It’s about being proudly deaf, a core part of your identity. “Little d deaf is almost more of a medical perspective, like you’ve got a hearing impairment.”

Jenkins is not a fan of terms like “profoundly deaf” (which the school’s Ofsted report uses), since it assumes there is something deeply wrong with the student. We wouldn’t say someone was “profoundly black”, I reflect.

So why is this not a louder national conversation? “People don’t realise you have an identity there,” Jenkins nods.

He says deaf history is an important part of developing this. One key date astonishes me: in 1880, a conference in Milan banned sign language in schools across Europe and the US, believing oralism to be “superior”.

The law led to many deaf teachers losing their jobs, no longer able to speak their first language. BSL was only allowed again in English schools in 1975, says Jenkins.

The struggle of deaf history is alive right now, too. Technology, such as web cams and Zoom, has revolutionised the world for deaf people, says Jenkins (he remembers when his parents’ generation had to use a “minicom” – a phone that typed).

But basic rights are still lacking.

Only now is a bill – backed by government – making its way through parliament to make BSL a recognised language in England, which would drive up accessibility rights for the community.

Although it was recognised as an “official” language by the UK government in 2003, it does not have legal status.

“We need to think of this as our fourth indigenous language,” says Jenkins.

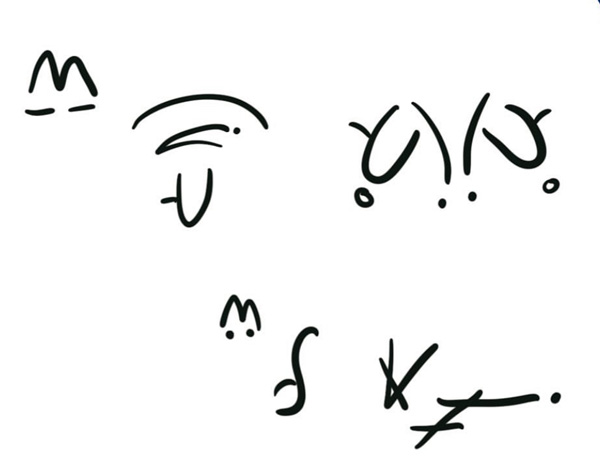

(Extraordinarily, he is also doing a PhD where he is designing a written form for BSL, using symbols, or “glyphs”. If it works, it would be the first-ever sign language script of its kind.)

By this point, I’m so desperate to communicate directly with Jenkins, I’m feeling pretty cross BSL wasn’t offered at school. Should it be?

“Some primary schools are doing it – but deaf people should be teaching it, and there are still lots of barriers for them.”

But there’s the next challenge – only last week a report revealed the number of fully qualified teachers of the deaf has fallen by 16.5 per cent.

There are now only 887 fully qualified teachers of the deaf, compared with 1,062 in 2011, according to the Consortium for Research into Deaf Education. “We need more role models. It’s a desert out there.”

Jenkins is bent on helping his students build confident and secure identities and senses of self, rather than feel inadequate or disabled.

It’s truly awe-inspiring. Let’s hope his work keeps getting louder.

Your thoughts