Education funding in England has become “less progressive” over the last decade, with efforts to target cash at poorer pupils diminished by demographic changes and government policy decisions.

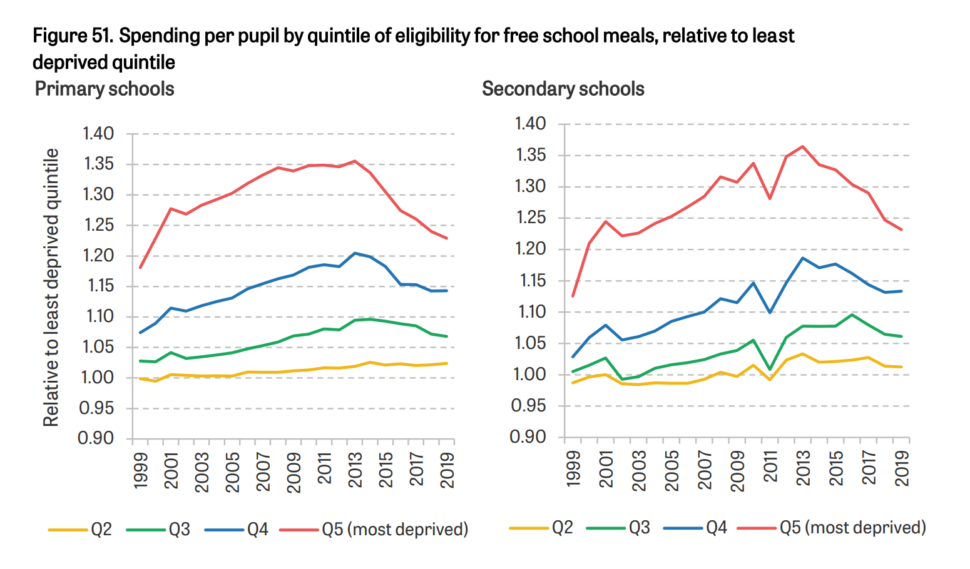

The Institute for Fiscal Studies found that the extra funding for schools with disadvantaged intakes fell from around 35 per cent in 2010 to less than 25 per cent in 2019, about the same level as it was in 2000.

The report also found the gap between state school funding and average private school fees in England has more than doubled since 2009, from £3,100 to £6,500.

The figures will make for uncomfortable reading for the government, which has claimed in recent years to be “levelling up” deprived areas of the country.

More deprived schools receive additional funding through the national funding formula and measures like the pupil premium, which is supposed to fund initiatives to support disadvantaged children.

Analysis by the IFS shows how the funding system became “substantially more progressive” in the 2000s. Primary pupils in the most disadvantaged schools went from attracting around 20 per cent more funding than those in the most affluent to receiving about 35 per cent more a decade later.

But these patterns “have reversed since 2013” despite the implementation of the pupil premium policy, with the effective funding premium for disadvantaged schools falling to less than 25 per cent.

Funding changes benefit affluent areas

Much of this “erosion of progressivity” is due to the changing demographics of disadvantage, the IFS said. The overall share of pupils eligible for free meals fell, and eligibility fell in areas like London.

However, “more explicit policy choices” also played a role.

The decision to freeze the pupil premium in cash terms meant it became smaller as a share of overall funding. And the government’s minimum funding floors in the national funding formula have “tended to benefit more affluent areas”.

However, while the “progressivity of funding in the state sector has declined in recent years, it is still the case that the system remains progressive: it targets more resources to schools with more disadvantaged pupils”.

The findings come amid warnings that recent increases in school funding will not be enough to meet the impact of inflation and recently-announced staff pay rises. Schools Week revealed last month that many leaders will be forced to consider staff cuts to fund pay rises next year.

The IFS warned earlier this month that as a result of rising inflation, per-pupil funding will actually be 3 per cent lower in real terms by 2024-25 than it was when the Conservatives came to power, meaning ministers will not meet a promise to restore funding to 2010 levels.

In its report, the think tank called on the government to invest in education, adding there was “increasingly clear evidence that spending really does matter for pupil achievement – though, of course, resources need to be used well to be most effective”.

It warned government spending on education “has fallen significantly over the last decade, especially on further education, and funding for the COVID recovery package in England is likely to fall short of the scale of the challenge”.

‘No change’ in disadvantage gap for 20 years

The IFS report also warned there has been “virtually no change” in England’s disadvantage gap in 20 years, despite “decades of policy attention”.

The research paper found that while GCSE attainment had increased over time, 16-year-olds eligible for free school meals were still around 27 percentage points less likely to receive good GCSE grades than their better-off peers.

The report on educational inequalities warned that disadvantaged pupils start school behind their peers, and the education system is not succeeding in closing these gaps.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the ASCL school leaders’ union, said the research showed “we remain a deeply-divided, class-ridden society with a depressingly close alignment between family income and educational attainment”.

“To break out of this circle we cannot just keep doing more of the same. Government policy is in a rut of meaningless targets, empty rhetoric and pitiful levels of funding. The attainment gap between disadvantaged and other children starts early in their lives and widens as they grow older.

“We need to see investment in early years education, better support for schools which face the greatest challenges, funding for schools and post-16 education which matches the level of need, and a rethink of qualifications and curriculum so that they work well for all learners.”

Your thoughts