Councils across the country are routinely failing in their legal duty to provide full-time education for excluded pupils within six days, a Schools Week investigation has found, with some youngsters waiting two years for provision.

In some areas, not a single excluded child was placed in suitable education within six days – despite laws that councils must deliver this.

The average time for finding provision for excluded pupils also worsened in many areas, as exclusions hit record highs.

Sarah Johnson, an alternative provision consultant who has worked in the sector for 20 years, said the education system was “running into a crisis”.

“Access to education is not an ‘add-on’ or a ‘nicety’, it is a fundamental right enshrined in the UN Rights of the Child.

“If we know we are failing to meet our statutory duties to provide suitable full-time education, then we must ask ourselves: what systemic failures are preventing children from accessing school?”

‘We should all be worried’

Statutory guidance on permanent exclusions states councils “must arrange suitable full-time education for the pupil to begin from the sixth school day after the first day the permanent exclusion took place”.

Schools Week asked local authorities for data on how often they met this duty for excluded pupils over the past three years. We also asked about the average and longest times excluded pupils waited for provision.

Of the 58 councils that provided figures for last year, just over three quarters failed to place all excluded pupils in full-time education within six days.

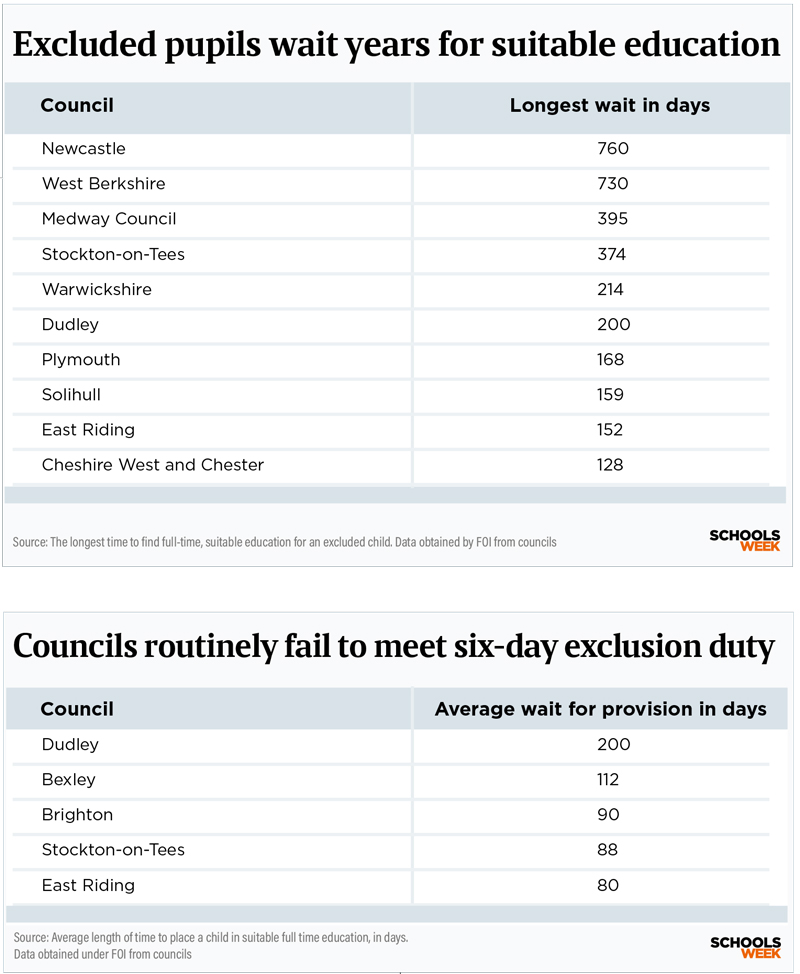

Seven had at least one child waiting six months or more for suitable education last year, 30 times longer than the law demands. Two had pupils waiting two years.

But it wasn’t just the odd pupil waiting longer. In 12 areas, three quarters of the excluded pupils that year were not in suitable education within six days.

Many councils also said they did not record the data – suggesting they may not be aware of the scale of the problem.

Kiran Gill, the chief executive of the Difference charity, said: “We should all be worried that the most vulnerable children – those who stand to gain the most from the belonging and purpose of being in school – are not in education at all.”

A Department for Education spokesperson added: “These shocking figures highlight devastating levels of disruption to children’s learning and the scale of the challenge we have inherited.”

‘Vulnerable children at greater risk’

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (BCP), Cumberland, Dudley and Warrington councils had the highest proportion of excluded pupils in 2023-24 not in suitable education within six days (all over 90 per cent).

In BCP, 65 excluded pupils were not in education within six days last year, despite just 36 exclusions, suggesting some of the 119 pupils excluded in 2022-23 were still awaiting provision.

Youngsters in the area waited, on average, 41 days.

Councillor Richard Burton, BCP’s cabinet member for children, said pupils waiting longer than six days were “typically those who are unable to benefit from rapid online learning solutions.

“This reflects that online learning for younger children or children with specific needs does not provide an appropriate form of learning. In these cases, bespoke solutions are developed and commissioned working with multi-agency professionals and families.”

In Medway, the average wait last year was eight weeks. One pupil waited 13 months. The council said increasing exclusions and a “limited number of options and ongoing SEND funding crisis means [meeting the duty] is not always possible”.

Alternative provision is funded from the high-needs block, which is already overspent in many areas.

‘Challenges around suitable space’

Newcastle and West Berkshire both had a pupil who had been waiting two years – at least 730 days – for a place.

Newcastle said the delays were down to “challenges around suitable space, the complexity of pupil needs, and a shortage of registered providers”.

West Berkshire did not respond to a request for comment.

Permanent exclusions in both areas have soared over the past three years. Exclusions are at a record high across the country after sharp rises post-Covid.

Dr Patrick Roach, the general secretary of the NASUWT, said difficulty in accessing alternative provision affected how schools supported pupils at risk of exclusion and “seriously” hampered efforts to keep pupils and staff safe.

“After over a decade of underfunding, external services for pupils are on their knees. A world-class education system has to include timely access to alternative provision if we are going to provide equal opportunities for all our children and young people.”

Situation worsens in many areas

Dudley, where one excluded child waited 200 days last year for provision, said it was “working tirelessly” to combat the rise in school exclusions, and claimed a new pathway strategy had reduced suspensions.

Warwickshire is also “strengthening” early support for primary pupils at risk of exclusion, and undertaking risk assessments in secondary schools to identity those at risk earlier.

But Newcastle said it has “limited direct influence” to bring down “record numbers” of exclusions because all its secondaries are academies.

Bexley’s average wait rose from 39 days in 2021-22, to 112 days last year – one of the biggest rises. The longest recorded wait last year was just under four months.

The council blamed the rise on parents refusing the provision offered, saying all the pupils in the data it provided had been offered a “suitable school place at the six-day provision”.

“Unfortunately, in some year 10 and 11 cases, parents did not accept the offered place.”

Brighton and Hove, where the average wait rose from 12 days in 2021-22 up to 90 days last year, also said some delays were down to parents, “especially if there are strong parental views that need to be considered”.

Bexley also said academies having their own admissions authorities “at times leads to delays in the offer of a school place”.

But Gill added: “Where are these children? At home with nothing to do they’re at greater risk of worsening mental health, criminal exploitation or susceptibility to online conspiracy theories and extremism.

“Without education and qualifications, these are children likely locked out of our workforce for years to come. This is a national and rising challenge post-pandemic, and the numbers affected are really alarming.”

Kids ‘not left to their own devices’

In Dudley the average wait soared from 23 days in 2021-22, to 200 days last year.

However, David Stanley, Dudley’s cabinet member for children’s services, said: “While we recognise there is concern over delays in children returning to education full time following an exclusion, they are not simply left to their own devices.”

Councils said while pupils may not be in full-time schooling, they are provided with at least part-time education.

Stanley said this might involve tutoring or use of AP, with pupils “monitored through our dedicated team until they can return to full-time mainstream education”.

Newcastle said its “interim solution” was an “inclusion key worker” for each child, which it said had helped integrate pupils back into education.

Medway said children not in full-time education after six days also got a “face-to-face tutor from our tutoring framework”.

But a Schools Week investigation last year found that excluded pupils waiting for specialist provision in more than one in ten councils had no provision at all.

Others were receiving less than full-time education, with some getting online tutoring only.

Theresa Kerr, partner at Winckworth Sherwood, said: “We know that many alternative provision schools are full, but there are significant safeguarding risks if children are not in school because they are waiting for a place – the statutory timescales are there to offer this protection.

“It also makes the prospect of reintegration back into mainstream school much harder for them if they fall even further behind with their education, and can ultimately affect their long-term life chances, with the risk of falling.”

‘Full-time’ duty grey area

Ed Duff, a director at HCB Solicitors, said the findings seemed to be a “result of public services being crippled financially to the point where there are plenty of excellent sounding duties, but it’s impossible to comply with them.”

But he said one of the issues around the duty was the lack of definition for of what constituted “full-time” education.

“As such, any education could in theory be deemed or at least argued to be ‘full time’ – so for councils to acknowledge the level of pupils not in full-time education [in their FOI responses] is a concern.”

The government said schools now have a statutory duty to provide daily attendance data, which includes a code for pupils attending education provision arranged by councils – meaning there is “greater oversight”.

The DfE spokesperson added “we know there is more that needs to be done to support [excluded pupils] and that is what this government is delivering.

“We are tackling the causes of poor behaviour at their root including by providing access to specialist mental health professionals in every school, introducing free breakfast clubs in every primary, and ensuring earlier intervention for pupils with special needs as part of our plan for change.”

Lots of excuses and no solutions . Many schools and councils don’t have a child centred approach which truly understands the needs of the child. League tables in schools have contributed to many children missing out on education because they don’t fit the right profile. But many services to support children and families have been cut so more and more responsibility is placed on schools and Local authorities who don’t have the expertise or staffing to better understand the needs and support required for these young people. The fact that the government is shocked by this astounds me . The whole system of education provision is broken and they don’t know how to fix it and won’t take accountability . Go back to basics and identify the needs of children today and what they expect of schools. A massive conflict exists between what the government expects from providers of education to what children actually need because the model for educating and supporting children is outdated and underfunded and services just don’t work together. The culture of who is to blame needs to shift to a culture where solutions are sought based on a true understanding of children’s needs their strengths and their interests. If the government worked backwards and looked at the skills it needs to create a workforce that builds a strong economy then it will be obvious to see why the current system and support services don’t work.