Five years after they were set up, research schools haven’t enjoyed much public hullabaloo. Jess Staufenberg visits a lead school to find out what’s really been happening

James Siddle has always been on a search for good evidence. The headteacher at St Margaret’s Church of England primary, a local authority school in Lincolnshire, used to have a list of the top ten performing schools locally, and would visit them one by one.

A classroom teacher at the time, he wanted to “get better” but “used to feel it was just about who had the loudest voice in the staffroom. I would feel quite frustrated about understanding how we made decisions.”

He found some of the schools were “exam factories”, and remained unconvinced. But after reading a 2013 academic paper by Steve Higgins, professor of education at Durham University, on the minimal impact of teaching assistants, he reached out again.

“I emailed Steve and I said, ‘I find this really interesting and I don’t agree’. He ended up coming back to my school […] That for me was the gateway into evidence.”

Soon Siddle was involved in a project on teaching assistants with the relatively new Education Endowment Foundation – the charity set up in 2011 by the Sutton Trust to share evidence around closing the attainment gap for disadvantaged pupils.

He bumped into Professor Jonathan Sharples from the University of York’s Institute for Effective Education and heard that together, the EEF and IEE (which has now closed) were launching the Research Schools Network in 2016. Part of the thinking behind the scheme was that schools are more likely to listen to schools than to academics.

St Margaret’s primary, which has just 72 pupils, soon became a lead school within the Kyra Research School – a group of schools stretching across Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Cambridgeshire and North Hampshire.

With Siddle as director, it was one of just five “research schools” to win funding to spread evidence-informed practice, supported by the EEF, in 2016.

There are now 28 research schools and ten associate research schools (smaller hubs supported by the larger research schools). According to Stuart Mathers, head of dissemination and impact at EEF, each research school gets a core EEF grant of £40,000 a year.

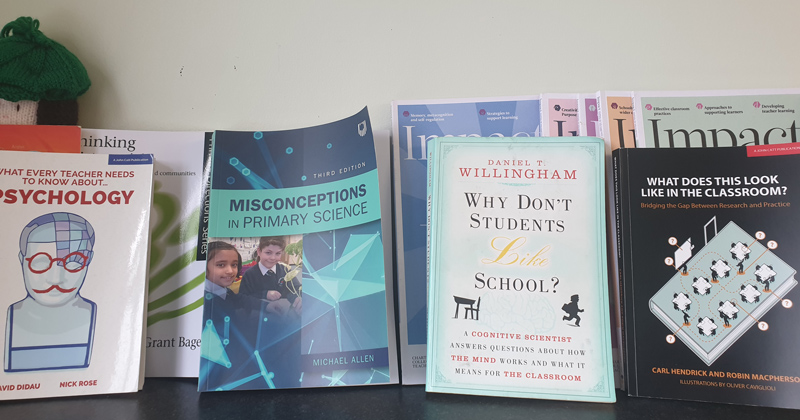

Sitting in Siddle’s staffroom, the first thing I notice is a shelf packed with papers and books. Titles such as What Does this Look Like in the Classroom: Bridging the Gap between Research and Practice and Why Don’t Students Like School? (by a cognitive scientist, according to the subtitle) rub shoulders with lots of “guidance reports” from the EEF.

These range from Improving Behaviour in Schools to Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning.

The guidance reports are the starting point for an evidence-based school, explains Amy Halsall, assistant head, who has come to fetch me for a year 6 lesson. Each report is a culmination of the EEF reviewing available academic evidence, then running a panel with “expert voices” of teachers to understand what staff most need help with.

Halsall, for instance, sits on the primary science expert panel. Then the EEF either runs a trial of the intervention, or, if the evidence is already solid, produces a guidance report straight off.

I want to know I’m taking the best approach possible

For Halsall, a former biologist, the experience is professionally motivational: “It gives me the knowledge that I’m doing the best job I can. I want to know I’m taking the best approach possible.”

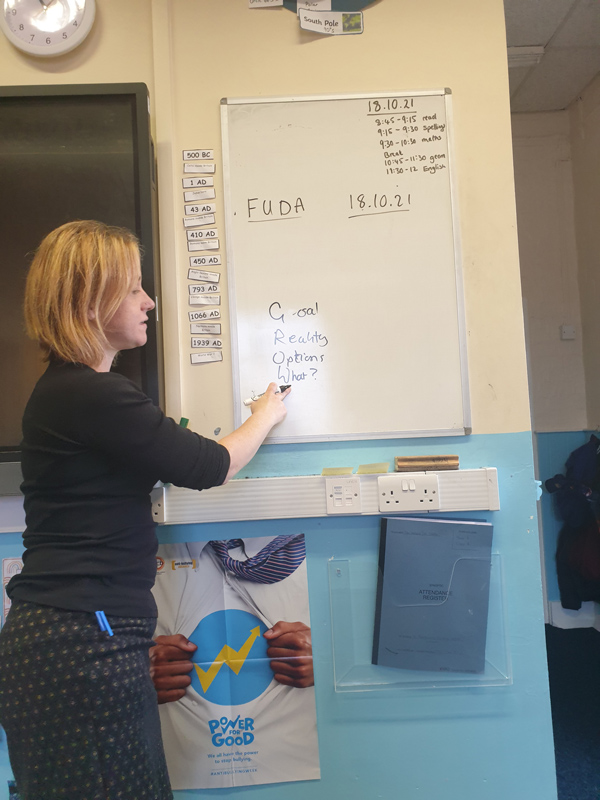

In front of me, year 6s are now doing a “follow-up diagnostic assessment” in maths. Halsall sets them sums to ascertain their knowledge, then runs a lesson, then a follow-up assessment 24 hours later, then a week later, then a month later.

This approach is based on education theorist Dylan Wiliam’s “hinge questions”, explains Halsall, which are questions used to identify key points in a child’s learning.

It’s also linked to a trial Kyra Research School itself carried out, which looked at the most effective gaps of time to leave between assessing students by year group.

About 400 pupils took part, and the evidence revealed that smaller gaps between assessments worked better for younger students. This approach was then adopted across the research school, says Siddle.

Meanwhile, letting pupils know why they are doing these diagnostic assessments is also informed by the research on metacognition, explains Halsall. “It’s all about self-regulation. The children should have an understanding of the success criteria, so they know how to improve their own work.”

The EEF’s report states that developing “pupils’ understanding of what is required to succeed” adds, on average, an additional seven months’ progress.

Now the pupils fold up their Chromebooks and trot outside into a giant polytunnel, for a geometry class with compasses and protractors. Again, the EEF has a guidance report showing that “outdoor adventure learning” can improve self-confidence and self-efficacy (the school has recently bought a new climbing wall and obstacle course).

But Siddle also points me to research on “episodic” and “semantic” memory, which informed how the school decided to use the giant physical graphs outside, made of rope and wood.

“Episodic memory means you remember you were outside, which can help you remember what you were learning, but it might also distract you. You want to bury what was learned in the pupils’ semantic memory,” he adds.

It’s another reason to repeat low-stakes assessment, even when working with giant outdoor equipment. “By repeating assessments, the children are more likely to remember the teaching points, rather than just being outside.”

The school’s attendance policy was also tweaked two years ago, based on a randomised control trial in the US. This showed that sending postcards home comparing a pupil’s lower school attendance to the average attendance improved attendance by 2.4 per cent, says Siddle.

Last summer, Halsall even rewrote the school’s behaviour policy based on the latest evidence. Now students start the day working on a task, rather than lining up outside to a whistle.

Both he and Halsall ooze a deep enthusiasm for what they are doing. The 17 EEF guidance reports are just the beginning, says Siddle. “What you have to do is start to read deeply and really understand the evidence.”

He gives his staff at least one half-day a week to engage with research, and recommends school leaders put aside time to “buy books, sit down and read the evidence”.

Buy books, sit down and read the evidence

To spread evidence-based practice, in 2018 Kyra Research School also created new roles called “evidence leads in education”, or ELEs. “These are evidence advocates in schools,” explains Siddle. Successful applicants get a three-day training course in “research design and how to understand evidence” with Kyra Research School.

They’re then “deployed” for six days in the year to share practice. There are now 50 ELEs across the network, and the model has been adopted by most research schools, says Siddle.

A 2017 Ofsted report of the school, which maintained its ‘good’ rating, found parents are “overwhelming in their praise for the efforts taken to develop their child’s passion for learning”, adding the school is “extremely caring”. Meanwhile, its performance outcomes in reading, writing and maths are all above local and national averages.

One potential issue I can see is the EEF, by focusing on the attainment gap, has mainly produced guidance reports on reading, writing, maths and science, with some on supporting special educational needs and behaviour.

But there are no guidance reports on arts subjects, for instance. “We’re pretty clear we’re about attainment, and we do focus on measures around maths and English and science,” says Mathers.

Siddle agrees that a school currently can’t be evidence based in everything it does, because evidence simply doesn’t exist in some areas, such as “arts-based interventions”. It would seem a scientific oversight not to look closely into performing, drawing and singing, simply because they’re not in SATs.

But even without those additional areas, Kyra Research School has its work cut out. An EEF report in 2017 found just a quarter of teachers cited academic evidence as influencing their decision-making, with teacher-generated ideas holding much more sway.

And the EEF’s own evaluation report of research schools in “opportunity areas” published this month says it’s still not easy to reach the neediest schools – with buy-in from leaders being the key factor.

If anything, it shows research schools have much more to do. “It’s not a silver bullet,” concludes Siddle. “But it is about best bets.”

Your thoughts