Female, non-white and part-time staff are significantly less likely to be promoted to headteacher roles, according to new official research.

A study by the Department for Education says the disparities exist even when “controlling for other factors” such as experience, location, phase and working patterns.

The DfE appears to have been forced to publish the workforce census analysis by leaders’ union NAHT, which secured part of the data, showing declining leader retention, earlier this week.

Here are the key findings from the “school leadership in England 2010 to

2020: characteristics and trends” research.

1. Men more likely to get promoted – and rise quicker

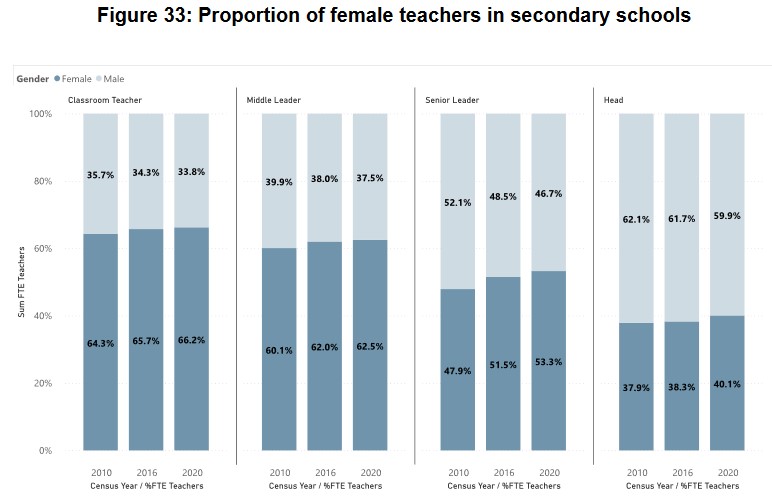

The share of female heads rose from 67 per cent to 70 per cent between 2010 and 2020 – but it remains lower than their representation among classroom teachers at primary and secondary.

DfE analysis also highlights “significant disparities” in promotions, with women 14 per cent less likely to be promoted to senior leadership (assistant or deputy head) and 20 per cent less likely to become heads. By contrast, women were just as likely to be promoted to middle leadership.

This finding is after controlling for other factors, such as age, experience, phase, working patterns or location.

The average man also progresses three years faster to primary headship and one year faster to secondary headship.

2. Leaders getting more diverse (but big drop in inner London)

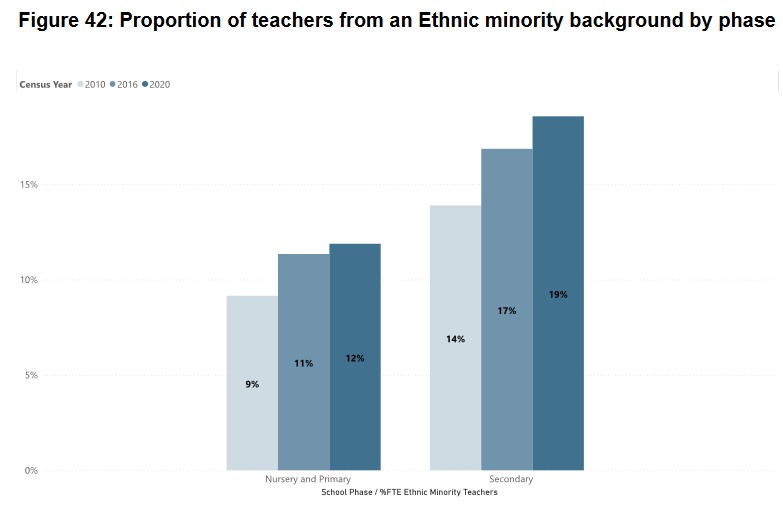

The teaching workforce is becoming increasingly diverse, including at leadership levels, but remains less diverse than the general population, the study indicates.

Ethnic minority leaders made up 7 per cent of primary heads and 9 per cent of secondary heads, both up two percentage points in a decade. New-to-post teachers and leaders are also more diverse than peers already in post.

But after controlling for other factors, non-white teachers were 18 per cent less likely to be promoted to middle leadership than white British ones, and 21 per cent less likely to be promoted to headship. No difference was found between white British and white Irish staff.

Ethnic minority staff overall were also disproportionately in London, even when factoring in its more diverse population.

But, interestingly, diversity among inner London secondary heads has actually fallen, from 34 per cent in 2010 to 25 per cent a decade on.

3. The trend for younger heads tails off

The average age of heads fell from 51 in 2010, to 48 in 2016, but this has since stabilised at 48 in 2020.

Senior leader median ages also fell from 44 to 42 in 2014, before stabilising.

The DfE said it could reflect higher retirement levels in the first half of the decade, which subsequently fell. These older staff were replaced by less experienced leaders in their 30s and 40s, many of whom will still be in post – reflected in average heads now being “somewhat more experienced” than in 2016.

Another previous trend, for increased senior leadership numbers as a share of all staff between 2010 and 2018, has also since tailed off.

Maintained schools also have more leaders than academies – which officials said could reflect lower use of teaching and learning responsibility payments and more leaders being employed centrally at trusts.

4. Female leaders five times more likely to work part-time

The proportion of part-time leaders has risen from 7 per cent to 11 per cent over the decade. Among female leaders it jumped six percentage points to 15 per cent, but among men it stood at just 3 per cent – only half a percentage point higher.

Yet further promotion “disparities” affect part-time staff, who are 51 per cent less likely to be promoted to middle leadership and 45 per cent less likely to make head.

“We expect around one part-time teacher to be promoted for every two full-time teachers,” the report read.

“This may reflect barriers to promotion for part-time workers, especially in higher leadership positions, but may also be the result of self-selection amongst those teachers with different priorities in terms of work-life balance, who might be therefore less interested in pursuing promotion.”

5. Retention fell over decade until Covid

NAHT analysis of DfE data published earlier this week showed new leaders in 2015 were less likely to last five years than their peers in 2010.

Thirty-seven per cent of new secondary heads new to post in 2015 were not in similar posts in 2020, down from 35 per cent among the 2010 cohort.

Similar trends were clear among deputy and assistant heads and middle leaders, with unions and Labour blaming high workloads, accountability pressures and a projected 21 per cent cut to real incomes over a decade.

But today’s more detailed report noted more recent improvements in most teachers and new leaders’ retention rates in their first year, put down only partly to Covid. The recovery has not been as significant for heads as teachers or other leaders, however.

Officials said the “increasing prevalence” of multi-academy trusts may affect the data, as many trust-level leaders are not included in school workforce censuses. Only leaders under 50 on permanent contracts were analysed.

Your thoughts