The education secretary has said he wants to see the free schools programme “spread much more widely” across England.

Gavin Williamson told fellow MPs this afternoon that existing free schools had been “far too disproportionately” created in London and the south east of the country.

I want to see this revolution in education delivery rolled-out, spread much more widely

Since the free schools programme launched, 172 of the institutions have opened in London, more than double the number that opened in any other region. However those that have opened outside of the capital have much higher rates of failure.

The education secretary’s intervention will be seen as important. It follows doubts about the future of the free schools programme. The Conservatives opted not to include a specific target for new institutions in their manifesto.

Williamson’s comments about the geographical spread of free schools also come less than a week after free schools pioneer Rachel Wolf, who co-wrote the Conservative party’s latest election manifesto, gave a similar warning in a column on the Conservative Home website.

During a debate today on the education elements of the Queen’s speech, Williamson heaped praise on free schools such as the Michaela Community School in north London, which he said had “changed the lives” of disadvantaged pupils.

But he accepted the programme in its current form was limited.

“These free schools that we have created, far too disproportionately, so many of them have been built in London and the south east.

“I want to see this revolution in education delivery rolled-out, spread much more widely through the midlands, the north and the south west of England. Driving up standards, driving up attainment in all of our schools, in all of our communities.”

However analysis by Schools Week found the free schools that have opened outside the capital are much more likely to have collapsed.

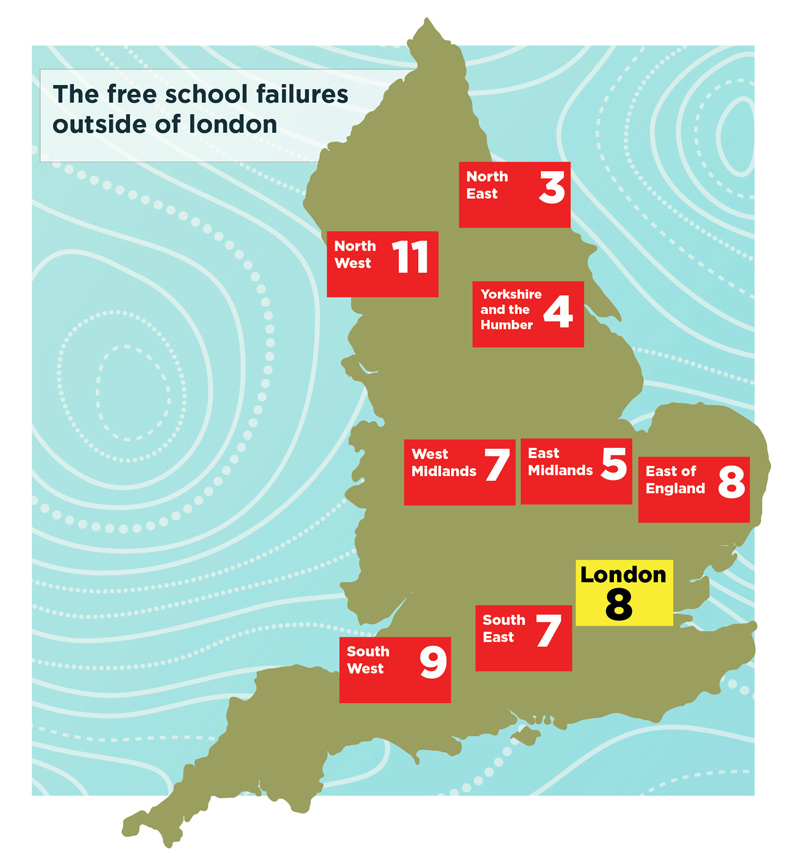

Of the 62 free schools that have closed, 54 of these (87 per cent) were outside the capital.

The figures include studio schools and university technical colleges, plus those that were rebrokered. The statistics were correct as of September last year.

Of the 20 mainstream free schools that closed, 15 were outside London (75 per cent).

Analysis of the 641 free schools that opened between September 2011 and September 2019 shows London received more than double any other region, with 172.

That was followed by the East of England (76), South East (75) and North West (74). However, just eight of London’s free schools (5 per cent) closed in this period.

Only two other regions had less than a 10 per cent closure rate – Yorkshire and the Humber, where four schools closed (8 per cent) and the South East, where seven closed (9 per cent).

In comparison, the North East saw three of its 15 free schools close – a closure rate of 20 per cent – while the North West lost 11 (15 per cent) and the South West lost nine (13 per cent).

These findings suggest there are other structural issues at play in the growth of the free schools movement, aside from the region where the schools are opened.

An Education Policy Institute report on free schools in October found secondary free schools are not being built in the areas with the greatest need.

However, it also found families were least likely to put a free school as their first preference, with just one fifth of primary and one quarter of secondary applicants doing so.

Free schools should only be provided when there’s a need for extra places. It threatens the viability of existing schools if new schools appear when there are already surplus places. Williamson assumes all free schools will provide ‘good’ places. But there’s no guarantee this will happen.

It’s not discussed much any more, but I seem to remember when the policy was launched it wasn’t just about new schools in areas which needed more school places, it was an opportunity to set up a new school if the existing options weren’t good enough. The intention presumably being to bring in competition driven by where parents wanted to send their children. It’s actually the scenario we see now in various places, without free schools but with falling populations. If the local area used to fully support two 1,000 place secondary schools, but due to changing demographics there are now only 1,000 secondary age children in the area it is not viable or appropriate to keep both schools open. In this situation the school that attracts more pupils will survive, and the other will close.

Mark – that’s still the case. But as I’ve said, there’s no guarantee that the free school will provide ‘good’ places and the failing local school may improve in the meantime. Far better to support a struggling school than open a new one which may threaten the viability of nearby ones whether less than good or not.

An impact assessment is drawn up when a free school is proposed. These look at the possible effect of a new school on nearby ones. They also record the Ofsted grading of nearby schools at the time the assessment was done.

These are not published until long after a free school opens. This is unacceptable. They should be available before opening so nearby schools and parents are fully aware of the possible impact of a new school. Sometimes even good schools are named as at high risk as I point out here: https://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2018/08/free-school-impact-assessments-contradictory-inconsistent-and-flawed

As ever there is no guarantee either way. The struggling school could potentially have been failing for so long it’s effectively toxic and it may be better to simply ‘start again’.

I do agree with you on the impact assessment. Greater transparency is almost always the way to go.

What happens if there are 1500 pupils? Enough to support one school, but not enough to support both? If one school full and the other closes where do 500. Children get places?