An “amazing achievement”. That’s how Nick Gibb, the long-time schools minister, describes the progress of his department’s £400 million scheme to deliver laptops to disadvantaged children.

He told MPs the delivery of 876,000 laptops, since the scheme launched in April last year, was an “amazing logistical exercise” amid a “demanding global market”.

But headteachers say too many pupils still do not have adequate devices as old tech starts to fail and live lessons mean laptops and phones can no longer be shared by several children in a household.

A new digital divide is also opening up as larger academy trusts use their financial might to purchase laptops, while smaller schools wait for government handouts.

So, what’s going wrong? Schools Week investigates…

Live lessons up demand

A Sutton Trust study published last week found 47 per cent of state schools had only been able to supply, at best, half their pupils with laptops, with two thirds of senior leaders having to “source IT equipment for disadvantaged pupils themselves”.

Before the pandemic, Ofcom estimated that 9 per cent of children – between 1.1 and 1.8 million – did not have access to a laptop, desktop or tablet at home.

The Department for Education has now delivered 876,013 devices. As the Ofcom figure is UK-wide, it suggests the DfE has provided a huge chunk of those needed in England.

But an Ofsted study this week found schools had also gone “out of their way” to ensure pupils had devices, including leaning on local businesses and using Covid catch-up cash.

There are also scores of campaigns – such as by the Daily Mail and The Mirror – to provide devices, so why is the shortfall not plugged?

Simone Vibert, a senior policy analyst at the Children’s Commissioner Office, said that the gaps were filled for pupils in need in the first lockdown, but schools soon realised there were many more who still needed access.

Fiona Chapman, the executive principal at Ark Dickens and Ark Charter schools in Portsmouth, said pupils needing devices came from “quite unusual corners”.

“Some families on pupil premium have access to every device they need. It’s been about speaking to each and every family.”

School leaders also say the DfE’s use of disadvantaged pupil numbers for allocating devices did not always reflect areas of need.

As revealed by Schools Week, the government assumed schools had as many as 282 laptops each in its calculation to decide how many additional free devices they would get.

Ofcom’s estimate only covers children “without home access”, rather than those without individual access, meaning that figure is likely to be much higher.

‘We are hearing of family laptops ceasing to work under the strain of three or four hours of teams calls’

A shift to live online lessons as schools boost their remote education in the new lockdown is also increasing demand.

“Most children now have a diet of multiple timetabled lessons during the day, which is creating demand for more individual devices in one family,” said Dominic Norrish, United Learning’s chief operating officer.

Cheaper devices, such as tablets, which were adequate in the first lockdown also did not have the keyboards and cameras needed for live lessons, he said.

Bill Lord, the head of Long Sutton County Primary in Lincolnshire, said some families’ technology was beginning to fail.

“We are now hearing of family laptops ceasing to work under the strain of three or four hours of teams calls […] and they simply do not have the financial ability to replace them.”

Four families faced this problem this week, but only one would qualify for a DfE laptop, he said. This was because the DfE allocated devices only to year 3 pupils and above, despite insisting pupils in years 1 and 2 must have at least three hours of remote education every day.

Julian Wood, the deputy head of Wybourn Community Primary in Sheffield, said a “patronising” attitude towards the youngest learners left his school having to make up the shortfall.

‘It shows how slow the government has been’

Many schools and trusts, including Lord and Wood, were complimentary about the number of devices allocated to them and were sympathetic to the logistical challenge faced by the DfE.

In October, the government slashed schools’ allocations to laptops by 80 per cent so that its stock would last longer, citing a global shortage.

United Learning noted the shortage in the first lockdown as demand rocketed and US tariffs on China’s exports slowed production.

But Gemma Abbott, a legal director at the Good Law Project, said: “It’s ten months later and hundreds of thousands of children still don’t have access. Why wasn’t this resolved in the summer? It’s catastrophic and shows how painfully slow the government has been”.

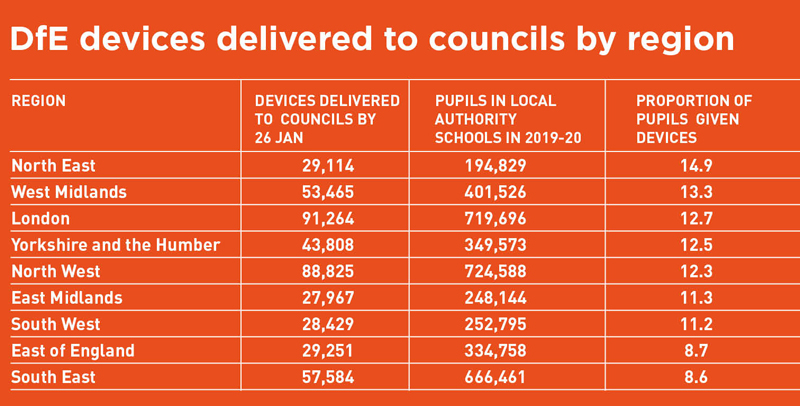

Delivery has also been varied. Councils in the north east, one of the worst hit regions in the pandemic, received the highest proportion of laptops, analysis of government data by Schools Week found. The south east, a recent hotspot, received far fewer (see table).

Meanwhile the UK “lags significantly behind our European cousins” for online learning, said Julian Drinkall, the chief executive of Academies Enterprise Trust.

He was referring to countries such as Estonia, where digital learning platforms were in widespread use well before the pandemic, and Finland, which has a national online library for education resources.

Schools Week was unable to find comparative data on laptops to compare England’s progress against other countries.

Scrutiny has now turned to the laptop suppliers.

The Good Law Project wants to know why Computacenter, whose founder Sir Philip Hulme is a Conservative Party donor, was awarded a £198 million contract to deliver laptops. Abbott said that “questions around cronyism” needed to be answered.

In November, the government brought two more suppliers onboard to help with supply, XMA, based in Nottingham, and SCC, based in Birmingham.

SCC is owned by the Rigby Group, which has donated more than £100,000 to the Conservative Party in recent years. Schools Week approached all three companies for comment.

Larger trusts pull ahead

But any global shortage has passed by the country’s largest academy trusts who have bought huge numbers of laptops.

Academies Enterprise Trust has spent £2.93 million, using six suppliers – more than the DfE.

Similarly, United Learning has spent more than £2 million on devices and wifi, buying 55 per cent of its 20,000 devices. Ark has received 5,500 devices from the DfE, but has distributed 12,000, in part through match funding received from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport.

But smaller schools have had to rely on the DfE’s allocation and donations from parents.

Carla Ferla, the head of Peareswood Primary in south London, said her school has received 60 devices – with 20 arriving this week – for an allocation of 72.

For pupils who are still waiting, the school has “signed up to a charity where people can donate” and paper packs will also be used.

Meanwhile, Colebourne Primary in Birmingham has entered a £130,000 three-year leasing deal to supply 300 iPads as it was the “only option” to ensure all pupils had a device. Parents will cover about £40,000 of the costs.

‘Low spec’ laptops and Russian malware

Concerns have also been raised over the quality of some of the DfE’s devices, particularly the GeoBook 1E, which comes with 4GB of RAM memory and 64GB of built-in storage.

It is the cheapest laptop you can ever buy with the lowest priority of performance

A secondary school IT support worker, who wished to remain anonymous, said the built-in storage wasn’t big enough to hold all the software necessary for home learning. The school opted to leave some programs out to get 154 of the devices set up.

“It is the cheapest laptop you can ever buy with the lowest priority of performance,” they added.

According to the Good Law Project, 90 GeoBooks at a school in Bradford were found to contain Gamarue.I malware, which the school said was contacting Russian servers.

A Yorkshire secondary asked parents this month if pupils could access lessons through their gaming devices as the laptops sent by the DfE were of such “a low specification that we were unable to install the necessary programs for students to access their work from home”.

When ordering, schools can pick between receiving blank devices or models preloaded with software.

Victoria Campling, the head of St Aidan’s Catholic Primary in Essex, ordered three blank GeoBooks in November. But a lack of on-site technical support meant they were not set up for pupils until January – with one laptop already returned due to a fault.

The DfE says under one per cent of laptops have been returned. All devices meet “minimum specifications”.

Would it be better to go to Currys?

Of the 1.3 million promised laptops, 423,000 are still to be delivered.

The DfE has refused to set a date for when it will reach the target, but if the current pace of 75,000 a week is maintained, schools face up to a six-week wait. The last of the laptops would be delivered in the week before March 8, when it is hoped schools will reopen.

Natalie Perera, the chief executive of the Education Policy Institute think tank, said because of the huge disparities in access to digital devices, the DfE “should consider whether it is feasible to release funds to schools”.

Robert Halfon, chair of the Commons education select committee, said this month that vouchers should have been given to heads to “go down to the local Currys and buy Chromebooks for £200”.

A live expert on Currys website told us while there had been shortages at the outbreak of the pandemic in March, it would have “no problem” delivering 50 Chromebooks to a school within a week of ordering.

But Jonathan Simons, a director at Public First, said the DfE was “too far down the road” to change direction. It’s now bought the remaining laptops and is waiting on delivery.

A spokesperson said the department was “acutely aware of the additional challenges faced by disadvantaged children”, with deliveries “continuing at pace”.

Correction: This article was amended to make clear the Ofcom study related to the UK.

The fact that Robert Halfon, in yet another attempt to self-promote, made a ridiculous comment about going down to Currys doesn’t mean it should be parroted without some degree of thought. Of course Currys can deliver 50 Chromebooks within a week – well done for that piece of investigative journalism. Now go back to your “live expert” and ask them how long it would take to deliver 800,000.

A maths problem for your readers:

If there is a £400 million scheme, supplying 1 million laptops like the GEOBook1E that RETAILS at less than £200 each, without bulk discount and including delivery and software, how much profit do the Tory crony suppliers make?

The government should have gone direct to the big computer manufacturers. They could have had them all bidding desperately for such a huge contract and got much lower prices as well as quicker delivery. Instead they go to a ‘middle man’ friend of theirs.

A device is not a solution! It is a corner piece of a much more complex jigsaw which includes the crucial pieces of connectivity, context, collaboration, communication , content, co-construction, community, creativity and caring, capable compassionate confident teachers…A device is just that..a device and without the other bits a useless bit of tin

I do think the lack of devices in primary school has been exposed during this pandemic. We already bought into the digital platforms two years ago after visiting a school in the LGFL. We just felt that there is always going to be ‘more technology’ We are a junior school with 256 pupils and by autumn 2020 we had 128 chrome books on trollies (leased so we know exactly how much we are paying out each year & always up to date) that pupils use all week (google classroom). We dismantled the old ‘ICT SUITE’ at the same time – seems archaic now! Thus when the time came we loaned out all the stock not being used for kids in school over the course of one day, our teachers and pupils and parents knew what they were doing with the kit and I just had to think about getting the free data for a few parents. We are not a well off area but have 100% access. I do think that schools should also think about future planning and investing for technology too rather than waiting for handouts from the sclerotic DFE. Learning in school and at home needs to be more seamless. Otherwise, yes they are just pieces of metal that no one knows what to do with…