Ava Sturridge-Packer’s sparkling CV is the result of overcoming injustice, writes Jess Staufenberg

It was 1982, and now-education consultant Ava Sturridge-Packer rang a school where she had an upcoming interview to warn she wasn’t Catholic. Invited along anyway, she waited patiently in reception. But the school’s headteacher never appeared. Eventually, his secretary came out and said “sorry, there’s been a mistake. You’re not Catholic.” Sturridge-Packer replied, “I told you that on the phone”.

But the head never arrived, so, as she puts it, Sturridge-Packer “scuttled back home” to the school where she was teaching in the west Midlands. Her headteacher offered to demand to know why she hadn’t been interviewed, but Sturridge-Packer refused. “In those days, in terms of some of the overt racism you faced, there was a lot of acceptance just to not rock the boat. So I said no.”

More than two decades later, Sturridge-Packer is an in-demand school improvement advisor across Birmingham, with a sparkling CV that includes being a national leader of education and retention and recruitment advisor for the Department for Education. To top it off, in 2000 she was made a CBE for services to education.

Today she’s emanating positivity in the office of Grestone academy, one of the schools she supports, in a space adorned with supportive messages. Framed slogans on the walls say “Teachers who love teaching teach children to love learning” and “Smile and the whole world smiles with you.”

Sturridge-Packer, who’s constantly on the edge of cracking a joke, informs me confidentially that she asked to “make the office beautiful” – with little mirrors on the walls, a big plant and silver cushions on chairs. A modest photo of her with the Queen stands on the windowsill. Only one slogan hints at the struggles she’s faced: “I believe in being strong when everything else seems wrong.”

Following that fateful experience, the young Sturridge-Packer would ask a white friend to take in her teaching job applications instead, waiting until the interview to show her own face. “I wanted to check my application was alright,” she explains. Not long after, Sturridge-Packer got a call from Shaw Hill primary school in Birmingham offering her a job as a reception teacher. “I said, ‘well, you need to know I’m black’. And he just laughed and said, ‘that’s not a problem for me’.”

Sturridge-Packer describes this head, Jim Carr, as an “absolutely amazing person who nurtured his staff”. She developed her teaching skills from age 23 to nearly 27 and attributes the fact she and her colleague from an ethnic minority background both became heads to “Jim’s encouragement.”

But the road has been tough. Sturridge-Packer recalls overhearing parents saying “tell that f****** black girl to get the kids out.” Another time, a bank clerk refused to hand back her card and money. Later they rang her at school to say they’d made a mistake. “It was 1987. That was the world then.”

“It was 1987. That was the world then.”

In a week when ruthless press stories about Meghan Markle – which her husband has accused of “racial undertones” – seems partly to have prompted her and Harry’s decision to step back from their royal roles, it is clear racism in this country is far from dead and buried.

Sturridge-Packer herself is part of the Windrush generation, people who moved from the Caribbean on the encouragement of the British government to the UK to help with labour shortages after the Second World War. The generation became a household name when Theresa May’s government began wrongly deporting children of these Commonwealth citizens.

That political scandal only broke just over a year and a half ago. “With everything that came out about Windrush, I’m shocked how lucky I’ve been,” says Sturridge-Packer.

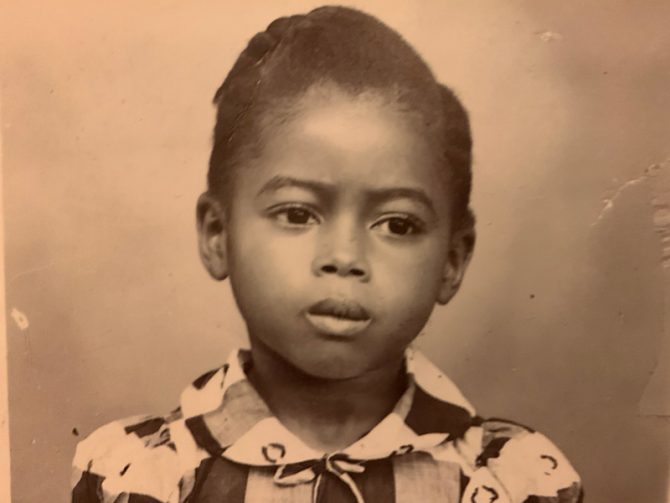

She speaks with clear admiration about her parents who navigated these tricky waters. They moved from Jamaica and sent for her when she was five. “My parents were smart, they sent for me at the beginning of the education system.”

Her work ethic she gets from her father, and her aspiration from her mother. They taught her she needed to be “twice as good” as her white compatriots to succeed. Sturridge-Packer’s father worked for British Rail and never missed a day. “That went against everything I used to read about black men and their poor work ethic.”

Meanwhile, her mother was educationally ambitious for her children. One of Sturridge-Packer’s most enjoyable qualities is being able to tell a heartbreaking story with perfect comedic delivery – none more so than when she failed the 11 plus. “When the results came out, it was like a bereavement in the house. It was like ‘oh my goodness, we’ve done everything for this girl and she can’t even get into grammar school!’” Then at 18 she failed to get the grades for law school. “It was another time of ‘close the curtains, this is terrible’,” Sturridge-Packer remarks cheerfully.

Eventually, she confessed to her parents. “I’d had this private thing that I wanted to be a teacher, but that wasn’t in the two professions my parents had in mind.” Expectations were particularly high as several family members are successful footballers: her brother, Dean Sturridge, was a striker for Leicester City and Wolverhampton Wanderers. Her nephew is also former Liverpool and England striker, Daniel Sturridge.

But her mother soon bucked up when she came to one of her daughter’s teacher training days at a Catholic college in Birmingham. “All these people were in their dog collars. I didn’t think it was so cool, but my mum suddenly said ‘isn’t this wonderful!’ I didn’t tell her it was just a conference of priests.”

With parental approval secured, the slog for approval within the education establishment began. With the support of Jim Carr, Sturridge-Packer moved to become head of first school at Wylde Green primary school in Sutton Coldfield. When parents queried the appointment, she invited them to meet her, and the complaints soon stopped. After that, she rejoined her former boss as his deputy, which she calls a “really happy time”. Then she looked around for a headship.

It took a lengthy three years. Still doing her “usual trick” of sending her application with a white friend, at one school she was described as “too young” – even though they had her age on her CV. In another, governors were “visually shocked” when she arrived. At a third, an advisor told Sturridge-Packer the other candidate would have “to be sick over their shoes” for the interviewers to appoint her instead.

“Teaching wasn’t one of the professions my parents had in mind.”

But persistence paid off, and Sturridge-Packer became executive head at St Mary’s CofE primary school. She even stopped the school, which was placed in special measures within weeks, from being closed. Birmingham city council soon used her school as an example in turnaround leadership. She stayed for 22 years, a decision she attributes to her belief in “really getting to know the local parent community – it’s so important.”

You also wonder whether Sturridge-Packer stayed so long in her first headship because unconsciously she didn’t want to have to search for approval all over again.

Perhaps she was waiting for the world to change. Even when Schools Week contacted her, she double-checked we wanted to interview her, since she was no longer a head and now just sat on three academy trust boards and works as consultant for the DfE. Yes, we reassured her. It was the same about 11 years ago when Pearson rang her. “They said ‘we want you to be a judge for the National Teaching Awards’. I was flummoxed.”

So has the education establishment changed? In a moment of rare seriousness, Sturridge-Packer says “the thing that grieves me is, there was a small handful of black and ethnic minority [BAME] headteachers and 22 years later it’s almost the same.” There’s been a change in cultural attitudes, but stasis in the statistics.

Always practical, Sturridge-Packer is working with a small team to set up a mentoring programme for would-be BAME school leaders, launching later this month. But the task is daunting: latest government figures show 93 per cent of headteachers are white British, higher than the 86 per cent of teachers who are. Just 0.8 per cent of headteachers are black Caribbean women like Sturridge-Packer.

As a rare and shining example, let’s hope schools approve more teachers like her for headship – fast!

This is a great article about a great lady, however Jim Carr was head of Marsh Hill not Shaw Hill.