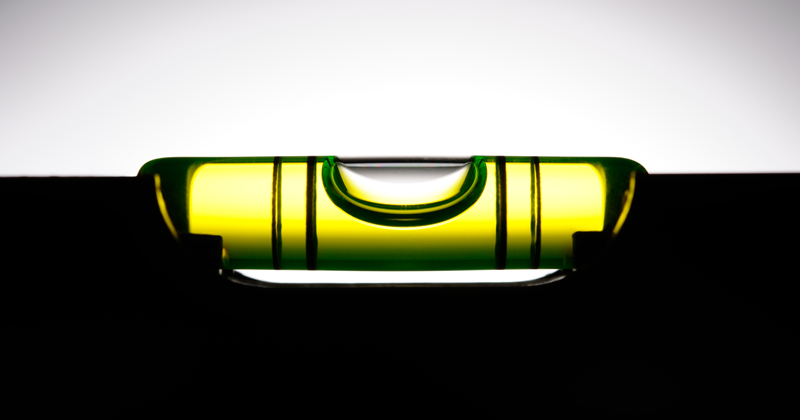

It has been a long wait to find out what the government really means by ‘levelling up’. With the pandemic capturing everyone’s urgent attention since shortly after the 2019 election, getting down to the business of fulfilling manifestos has been left in limbo for longer than usual.

We are now finally here with a published ‘Levelling Up’ strategy, but don’t hold your breath; the public will now have to wait even longer for its delivery.

The government has set a deadline of 2030 for “12 bold national levelling up missions”, looking beyond the usual election cycle. While a focus on long-term goals is often frustratingly absent from education policy, eight years seems a short time to achieve the dizzying ambition of the mission for 90 per cent of children to achieve the expected standard in reading, writing and maths by the end of primary.

A revealing exercise is to work out where these target-year children are now. The 2030 cohort were born just before or at the beginning of the pandemic and have experienced severe disruption to normal home visiting and baby group activity. It’s unclear what the impact of missing these important opportunities for early intervention will be, and we may not find out until they start school. They are now in the year before free nursery entitlements. Other than some marginal funding increases for family hubs, the white paper does not offer any additional support in the early years.

The aim of the policy programme is to cover one-third of all local authorities in England, designating these as Education Investment Areas (EIAs) on the basis of their average key stage 2 and key stage 4 attainment over the three years before the pandemic. Mathematically, an ambition to take national attainment up by an additional quarter of children reaching the expected threshold by focusing mainly on one-third of local areas is a stretch.

The white paper is pretty coy about guarantees

But what will the EIAs consist of? The white paper is pretty coy about guarantees but suggests the potential for new free schools. In particular, it promises new regional specialist 16-19 maths schools and a UK National Academy. Beyond these business-as-usual policy proposals, existing schools will be able to apply for capital funding for rebuilds or repairs in advance of the usual single-year list – a chance to join the queue early for future years.

Schools in the EIAs are also promised support from hub schools, which again looks to be a continuation of existing policy. Previously announced teacher retention payments will also be targeted at the EIAs, along with a renewed push for schools to join multi-academy trusts, focused on those that have been judged ‘requires improvement’ twice consecutively.

But of the schools in this ‘2RI’ category nationally, a quarter are already sponsored academies. A further quarter are converter academies once deemed strong enough to stand alone. Since the academies programme was expanded from its initial focus on sponsored academies, its performance has been consistently undifferentiated from that of local authorities, with some strong, some weak, and the majority showing moderate performance. So first off, this commitment only seems to apply to half of the ‘2RI’ schools and, secondly, academisation is not a school improvement silver bullet.

Perhaps most tellingly, the mismatch between an extremely bold national target and a scattergun of business-as-usual commitments ignores the deep-rooted challenges that must be addressed in order to secure radical and sustainable improvement. The unhurried roll-out of school mental health teams in the face of a wave of increased mental health difficulties is critical for secondary schools, and there are also many additional needs to be met in primary schools.

Two in ten primary children are eligible for free school meals, and a growing proportion of them are living in long-term poverty. Two in ten pupils speak English as an additional language, and three in ten have been recorded with special educational needs or disabilities at some point during primary school.

So the levelling up strategy has at last arrived, but it appears hollow and stubbornly evasive of the challenges that have persisted and increased for over a decade.

Your thoughts