Only half of primary schools on a £22 million flagship government inclusion programme were given all the support on offer, an interim evaluation has found.

There was “strong support” from those involved for the “partnerships for inclusion of neurodiversity in schools” (PINS) programme.

But evaluators at CFE Research, Cordis Bright and the University of Exeter highlighted implementation challenges with the programme’s first year in 1,669 schools.

PINS aims to bring together education and health workforces to offer “bespoke, whole-school support” to mainstream primary schools, to help them better identify and meet the needs of neurodivergent pupils and improve their outcomes.

It is frequently referenced by the government as an example of work they would like to roll out further as they reform the SEND system.

Here’s what you need to know…

1. Only half of schools had all support hours

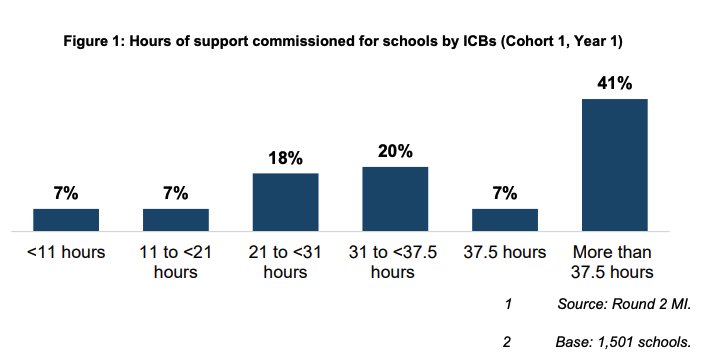

Integrated Care Boards, which organise local healthcare, had commissioned the “required volume of support” – 37.5 hours or more per school – in just 48 per cent of schools.

The reasons behind this include tight implementation timescales, lack of capacity among specialist staff – especially those in health roles – and limited capacity of schools to receive the training and support.

“Creative solutions” were used in some cases to overcome these challenges, but these often “relied on the strength of existing relationships”.

Evaluators found schools that received closer to the full hours “reported greater improvements”.

More formal commissioning and “a better understanding of local workforce opportunities” would be required in future.

The main issues the programme sought to address – wellbeing, attendance and behaviour – were the focus of commissioned support in a minority of schools (18 per cent, 12 per cent and 29 per cent respectively). The main focuses were neurodiversity, classroom strategies and sensory.

Four out of five respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that “the timescales for delivery had been sufficient to implement PINS”.

But most schools – 93 per cent – remained “active” throughout the programme through 2024-25.

2. ‘Perceived’ improvements in pupil outcomes ‘limited’

After a year of the programme, evaluators said evidence of “perceived improvements” in pupil outcomes was “currently limited”. But some teachers and practitioners said these “may emerge in the longer term”.

Evidence from case study schools highlighted some “positive changes” on wellbeing, attendance, attainment and behaviour. These were attributed “at least in part” to PINS.

Evaluators said measurable impacts on pupil outcomes were “not anticipated at this stage of the evaluation”.

There was “emerging evidence” of impact on leadership, culture and values, teaching and learning, the school environment, and relationship improvements between schools and parents. There was also “early signs” of greater understanding of neurodiversity.

3. ‘Overloaded’ SENCOs and specialist capacity issues

But evaluators said at this stage, it remained “unclear” what lasting impact PINS will have “on demand and pressures within the wider system”.

They found “ongoing challenges” related to “the level and complexity of SEND support needs” and “resource constraints and attrition among staff” doing PINs training, particularly SENCOs.

There were concerns about “overloading” SENCOs, who already have teaching responsibility and struggled to find time to pass the learning onto other staff.

Forty-three per cent of schools reported difficulties releasing staff for training.

When implementing change, some case study schools said a lack of staff had “inhibited the number of pupils who could be supported through small-group work or outside the classroom in dedicated quiet zones”.

“To compensate, teachers built quiet zones in their classrooms, e.g., tents or wigwams, so they could still supervise the children.”

Health boards also struggled. The scheme relied “heavily on strong existing relationships between ICBs and health practitioners and on practitioners goodwill – several examples of practitioners delivering support outside their contracted hours were given.”

4. Disagreement over which schools need help

Schools were selected through a range of methods, including direct approaches from ICBs, expressions of interest or geographical clusters.

Only 16 per cent of schools identified by the Department for Education with the highest potential need for PINS took part in the programme.

Just two-fifths (39 per cent) of schools in the first cohort had above-average proportions of pupils with SEND and FSM eligibility (43 per cent).

Evaluators said it led to concerns about “whether the programme was reaching the schools that could benefit most.”

Two thirds of those involved in the commissioning and design of the programme said they were either unsure (38 per cent) or disagreed (28 per cent) that schools most in need of PINs in their local area received it.

“Project team stakeholders occasionally indicated that a more strategic, nationally guided approach to school selection was needed to address this.”

5. Only 1 in 5 leaders said training and support ‘fully’ helped

Just 21 per cent of school leaders and SENCOs believed the PINs training and support “fully” addressed their priorities. But 58 per cent reported it met their needs to “to some extent”.

Evaluators suggested “the generic focus” of some training did not address their school’s priorities or take account of their existing practice.

But the support received by schools “was judged to be of high quality”. Direct access to health practitioners was seen as “particularly impactful”, given “the challenges schools typically face in accessing these practitioners outside the programme”.

The whole-school model – rather than just focusing on individual pupils – was noted as “the most impactful feature”.

There were “noticeable positive shifts” in schools meeting the needs of neurodivergent pupils.

“Practitioners reported that teachers and support staff were more inclined to apply curiosity and examine the reasons a child might be struggling, thus moving beyond responding to surface behaviours.”

As a result of PINS, more staff reported being committed to making reasonable adjustments to support neurodivergent pupils.

Your thoughts