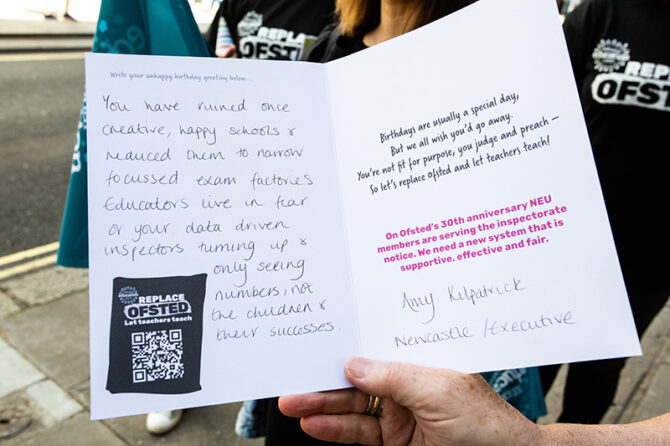

The National Education Union’s Replace Ofsted: Let teachers teach campaign marked the 30th anniversary of the establishment of Ofsted and calls on the infamous inspectorate to be replaced with a new system of accountability that is supportive, effective and fair.

Click here to find out more and sign the national petition.

Dr. Mary Bousted, Joint General Secretary of the NEU, explains why there is an urgent need for change…

In the same month that Ofsted was created in 1992 the then Conservative Government released its General Election manifesto and pledged to ‘introduce, for the first time, regular independent inspection of all schools’ to provide information on the performance of all local schools to parents ‘enabling them to exercise choice more effectively’, providing them with ‘straightforward reports on their child’s school, together with an action plan from governors to remedy any weaknesses.” As part of a wider drive within the manifesto to “extend competition and accountability in public services.”

Thirty years from these beginnings Ofsted is championed by government ministers as the guardian of educational standards in schools and colleges, providing indispensable information for parents. The many, very negative and damaging outcomes of inspection – the attrition on the teacher retention figures; the naming and shaming of schools given negative Ofsted grades resulting in these schools, usually those with disadvantaged pupil intakes, finding it much harder to recruit and to retain teachers and leaders, are justified by Ofsted as the necessary consequence of their ‘telling it as it is’ and not letting the context in which schools operate become a justification for poor educational standards.

Ofsted reports make media headlines. Current and past Chief Inspectors are wheeled out for frequent media interviews on education stories and Ofsted’s recommendations carry great weight in government policy making. Ministers may be irritated when Ofsted is critical of their policies but the appointment of Chief Inspectors who are, shall we say, closely aligned to government thinking, helps keep their relationship on an even keel.

All this happens despite the fact that Ofsted is a regulatory agency which is despised by the profession it regulates. 86% of NEU teacher and leader members, asked what should happen to Ofsted said it should be abolished – 41% wanting the agency to be abolished and not replaced, and 45% abolished and replaced by another inspectorate. Only 4% wanted Ofsted to stay as it is. [i]

All professions are wary of their regulator but teachers hate and leaders fear Ofsted. With good reason. One poor inspection result is too often career ending for leaders and career shaming for teachers. The shadow of the inspectorate glooms over the profession driving practices which teachers say are workload intensive but useless.

Teachers experience Ofsted as a force which creates fear and anxiety infecting almost all aspects of the working lives of teachers and leaders, and the relationship between them. In NEU focus groups of teachers the following comments were frequently repeated:

The senior leadership team are under immense pressure from the prospect of Ofsted dropping in at any moment. People are scared and frightened. SLT say ‘We’re not doing this because of Ofsted.’ But they are. People are frightened and it affects everyone in the school.

Ofsted just seem to release more and more things for us to do. Ofsted needs to change. I’m not saying there should be no accountability but to not have the same box ticking exercises.

Comment on Ofsted from an NEU member calling for the inspectorates replacement

As the prospect of an imminent inspection looms the internal monitoring activity in schools increases and intensifies. 56% of teachers and leaders reported that over 50% of their working time is taken over by Ofsted preparation in the run up to an inspection. That is a remarkable statistic – borne out by anecdotal, but frequently repeated tales told to me of teachers and leaders, when the notice period before an inspection was longer, spending the whole weekend in school prior to the inspection commencing the following Monday. The current inspection practice of one day’s notice has not, it would appear, relieved the pressure of a notice period, rather it has engendered a feeling of ‘battle readiness’ – for when the inspector calls – which could be tomorrow.

Now, if the evidence was clear that Ofsted was a force for raising standards of education then the workload, stress and pressure caused by its inspections might be worth it – that the price paid in teacher stress was justified.

So, how effective is Ofsted in raising school standards? How reliable are its inspection judgements? And how valid are Ofsted inspections? That is to say, do inspection judgements measure the quality of a school’s education provision, or do they measure something else altogether?

The short, and shocking answer to these fundamental questions is we simply do not know. And neither does Ofsted.

‘Since it was created over 25 years ago, Ofsted has not published any research to support the notion that their judgements on school accurately reflect the quality of education that a school provides’[ii]

Strangely, some would say, shockingly, given Ofsted’s claim to assess the quality of education provided by a school, Ofsted has never produced any research on the quality of its own inspection judgements. Ofsted has no evidence to support its assertion that the grades it awards are an accurate reflection of the quality of the education being delivered in a school because it has no evidence of the extent to which its inspection practices measure education quality.

Because learning is something that happens internally, within pupils’ heads, Ofsted relies on proxies for learning – lesson observations, and more recently work scrutiny – but has no evidence that these inspection practices, and the inspection judgements arising from them, do reflect teaching quality and pupil learning.

One startling fact reveals the extent to which Ofsted have a problem, and that is Ofsted have launched five different inspection frameworks over the past nine years (2010, 2012, 2014, 2015 and 2019).

The latest Ofsted inspection framework (2019) marks a decisive move by Ofsted away from its previous obsession with data of outcomes and test scores to a new focus on curriculum, measured through a schools’ intent, implementation and impact of its curriculum. Amanda Spielman, Chief HMCI honestly admitted: ‘For our part, it is clear that as an inspectorate we have not placed enough emphasis on the curriculum. For a long time, our inspections have looked hardest at outcomes, placing too much weight on test and exam results when we consider the overall effectiveness of schools. This has increased pressure on school leaders, teachers and pupils alike to deliver test scores above all else.’[iii]

Most importantly the current (2019) inspection framework requires generalist inspectors who will, in the main, have no degree in, nor experience of, teaching the subject or the age in which they are doing the deep dive, to come to valid and reliable judgements of education quality, through the ‘deep dive’ an intensive immersion into a subject area, or an age phase, comprising of lesson observations, work scrutiny and interviews with the teachers responsible for leading the subject or phase.

But can Ofsted really inspect a school’s curriculum validly and reliably?

The evidence suggests not. Prior to the introduction of its latest inspection framework Ofsted conducted small scale studies into the reliability of its inspection judgements, testing the extent to which different inspection teams, faced with the same evidence of education provision in a school, would come to the same judgement about its quality and would award similar inspection grades.

Pairs of Her Majesties Inspectors (HMIs) did ‘deep dives’ into particular subject areas and then had their judgements compared. Ofsted claimed that the reliability of the inspectors’ results was good – a claim that was quickly countered when it was revealed that none of the inspectors’ assessments, based on indicators such as lesson observations and work scrutiny, produced reliability scores above 0.5% and one indicator produced a score of just 0.38%.

Even more concerning is the finding that these numbers were an amalgamation of primary and secondary schools. When secondary school inspection judgements were considered separately, there was greater disparity in inspector’s judgements. Inspectors involved in the research study reported that they found it difficult to come to judgements about the quality of the curriculum through deep dives (lesson observations, interviews with curriculum leads and book scrutiny) in subjects in which they were not qualified.

As one informed commentator who uncovered and publicised these disparities in the inspectors’ judgements noted: ‘Remember that the inspector who visits your school could well be a non-specialist in the subject they are inspecting. To cap it all off Ofsted admitted that work scrutiny might not be possible in special schools, it may not work in further education and skills, it probably won’t be any use when judging ‘alternative methodologies in teaching and learning’ (e.g., Montessori schools) and it might not produce anything useful for modern foreign languages.’[iv]

It is hard not to see why this finding would not have been entirely foreseeable. As one critical commentator noted: ‘How will inspectors be equipped with the detailed knowledge and skills to make valid and reliable judgements on the extent to which the curriculum of a subject they have not taught, nor studied at degree level, is well planned and well sequenced? How are inspectors going to assess whether the curriculum reflects the school’s local context when they will spend, on average, two days in that locality?’[v]

Dr Mary Bousted delivering a speech at the National Education Unions annual conference in April 22

Every public service and the profession which works within it must accept proper and thorough accountability in the absence of which very bad things can happen. Without proper accountability poor professional practice can go unchecked; discrimination against particular service users can be rife. No one can seriously argue that teachers should simply be ‘trusted’ to do their work well.

But teachers and leaders should be able to have confidence that their work will be expertly judged; that the inspection grades will be comparable based on the evidence inspectors have evaluated and that their professional reputations will not rest on shaky foundations of inspectors’ knowledge and understanding (or the lack thereof), of subjects and age/phases in which it is entirely possible that they have no teaching experience and poor subject knowledge.

Any government serious about raising standards of education would seriously consider fundamental reform of an inspection system which has lost the confidence of the profession whose work it judges. Ofsted needs either substantial reform in order to render its judgements valid and reliable, or abolition so that a new form of inspection can be established.

Ofsted is despised by teachers and discredited in their eyes. The shadow it casts over schools drives teachers and leaders to find other work in which they can gain greater autonomy and agency. The fact that no government in the past 20 years has been prepared to delve into this serious issue, to think seriously about how it might be addressed, and then act upon it, shows a fundamental lack of seriousness of purpose when it comes to raising standards of education. And cowardice – where fear of tackling a difficult issue (radical reform of inspection) trumps the drive to ensure that there are enough teachers in the profession to teach the nation’s children.

Ofsted is in dire need of radical reform and the time for this to happen is fast approaching. The indefensible can no longer be defended.

Sign and share the NEU’s Replace Ofsted: Let teachers teach petition today.

[i] All the references to NEU teacher and leader members in this chapter are taken from a Delta poll of 1,746 NEU teacher and leader members. Data weighted to be representative of all members by gender, age, region, school type and school sector. Data correct to within +/- 2.3% at the 95% confidence interval.

[ii] Richmond,T. (2019) Ofsted’s Worrying Reliability Findings Won’t Comfort Heads who Get ‘The Call’ in a Couple of months, Schools week, 27 June. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/ofsteds-worrying-reliabilty-findings-wont-comfort-heads-who -get-the-call-in-a-couple-of-months/

[iii] Speilman, A. (2018) HMCI Commentary: curriculum and then new education inspection framework

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/hmci-commentary-curriculum-and-the-new- inspection-framework

[iv] Richmond,T. (2019) Ofsted’s Worrying Reliability Findings Won’t Comfort Heads who Get ‘The Call’ in a Couple of months, Schools week, 27 June. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/ofsteds-worrying-reliabilty-findings-wont-comfort-heads-who -get-the-call-in-a-couple-of-months/

[v] Bousted,M. (2019) How Will Ofsted Achieve Such Lofty Ambitions? TES, 14 February. https://www.tes.com/news/how-will-ofsted-achieve-such-lofty-ambitions

Your thoughts