Into headship before he was 30, Clive Lawrence has taken his special school to ‘world class’ status and an ‘outstanding’ grade. How did the cheeky boy from the estate get himself – and his school – to where they are?

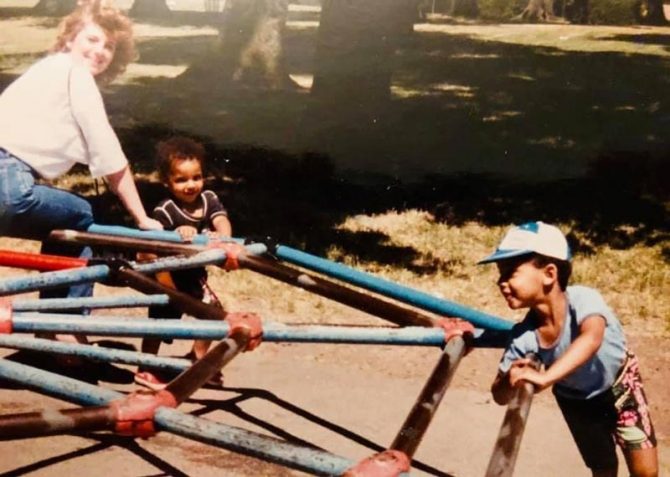

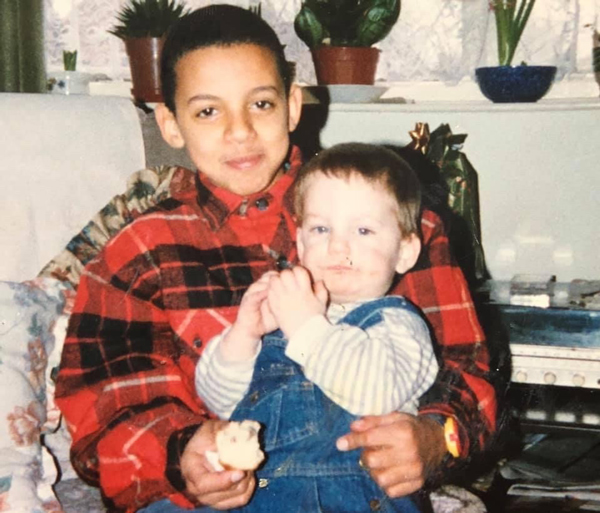

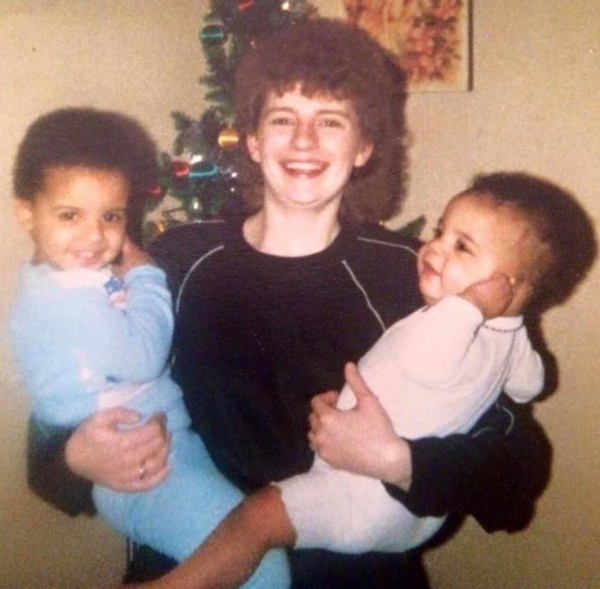

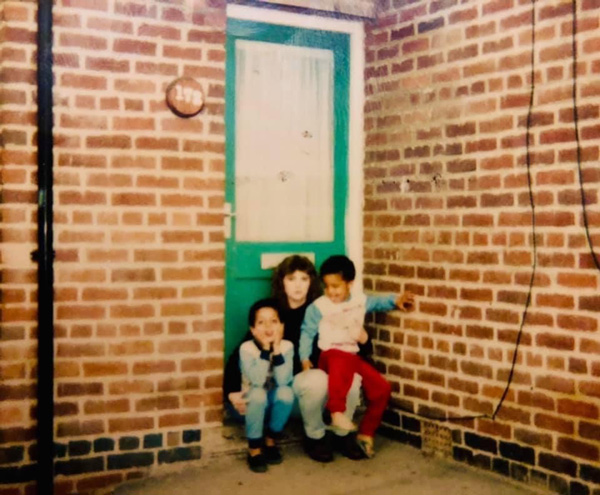

On his 28th birthday, Clive Lawrence was starting his first ever headteacher role. It was just five years since he’d qualified as a teacher and ten years since he’d volunteered as a teaching assistant, making him one of the youngest heads in the country. Perhaps even more extraordinarily, he’d come from circumstances that seemed to stack the chips heavily against him: he and his younger brother grew up on one of Derby’s most impoverished housing estates and were two of the only children from an ethnic minority background in the area. Their mum left school to have him aged 15 and brought him up in a white family as a single parent in the 1980s.

Now, aged just 35, Lawrence has a formidable record under his belt. He’s turned St Giles special needs primary school, in Derby, into everything from a teaching school supporting other settings to an internationally recognised “world-class” institution.

A special needs school that is leading the way on excellence for other schools is not a dynamic you often hear about.

With such a sombre backstory on the face of it, Lawrence could relate his personal tale with great seriousness. But he doesn’t. His eyes twinkle constantly. There is barely a moment when he is not chuckling or grinning, and it soon becomes clear that one of Lawrence’s qualities is as a top storyteller. I can’t stop laughing.

“Me and my brother were the only mixed-race kids in my family. When I think back to the terminology my nan used to use…” he breaks off, chuckling. “My nan would take us shopping with my cousins, and she’d say, ‘These are my white grandchildren, and these are my coloured grandchildren.’ She didn’t mean it badly! She loved us.”

He continues to smile as I ask where he grew up. “If you said you were from the Allenton and Osmaston estate like we were, that wouldn’t go down very well! But I loved it, I absolutely loved it. People said they wouldn’t walk through there at night but that would never have fazed me. Everyone knew everyone, everyone looked out for each other.” He also recalls “some cultural friction” in his early years between his mum’s family and his dad’s, who were from a Jamaican background. But both families loved the boys, he says, and the friction eased off.

Lawrence shares an ability to see the magic in situations with another storyteller of great importance to him: Roald Dahl. It was his primary school teacher, Mrs Farthing, who introduced him. “Bless Mrs Farthing, I loved her. She used to read us Roald Dahl stories all the time. I remember there were a lot of Irish traveller children in our school, so she read us Danny, The Champion Of The World,” he says, referring to Dahl’s book about a boy who lives in a caravan. “She was obviously trying to teach us about acceptance. That’s where I developed a love of reading, and of becoming a primary school teacher one day.”

The reality is that if there was a BA in headship, I would have done that

Primary school headship was in Lawrence’s sights from that moment, leading him on to a three-year BA Hons in primary education at Northampton University. When someone later asked him what else he would have done other than teaching, he didn’t have an answer. Leadership in particular drew him. “The reality is that if there was a BA Hons in headship, I would have done that degree,” he hoots. “I’ve always wanted to be a leader.” He leans in conspiratorially to the screen. “My mum came across a report from my PE teacher in year 2. It said, ‘Clive is really enthusiastic. However, I have to keep reminding him he’s the pupil and not the teacher, as he keeps trying to tell everyone what to do’.” He grins broadly.

The choice to seek inspiration – “I’m always quoting quotes, me” – and see the positive in situations is clearly core to Lawrence’s character, and also quite evident from the walls of his office. He shows me a framed picture of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in Quentin Blake’s brilliant drawings, with the quote “Nothing is impossible”. “I work in a special school, so I use that one quite a lot.” Another one from Dahl reads: “Those who don’t believe in magic will never find it.”

But, perhaps most unusually for a headteacher, Lawrence has his inspiration inked on to his very skin. Matilda, Charlie, James and the Giant Peach and the BFG are all intertwined in a huge tattoo on his right arm. I imagine it is a total trump card with shy children. “I had this dodgy tattoo there before, from when I was 15,” explains Lawrence. “So I thought I’d get something more…um…professional.” Like his stories, Lawrence has taken something that could appear rough and made it endlessly charming.

Yet Lawrence acknowledges that one of his other motivations for his work comes from seeing his brother struggle at school and in life. His younger sibling got in with the wrong crowd on the estate and was eventually permanently excluded from secondary school. “Teachers would also say things to him like, ‘you’re not like your big brother Clive’, which compounded the issue,” he says. Lawrence has been the special guardian of his younger brother’s three-year-old daughter since birth, with legal parental responsibility – a decision taken to help his brother out who was experiencing difficulties in life at the time, and to ensure his niece remained within the family. He holds a picture of a smiling little girl up to the camera, beaming himself.

So although Lawrence may have only been a teacher for five years before being made head at a primary special school in Staffordshire, one suspects he has been watching and learning closely for many years. Circle of life stuff was close to home. From age 15 he’d volunteered with a holiday camp for disadvantaged kids in Derby, and in the archive of black-and-white pictures of the camp he found a picture of his mum, who’d gone there herself as a child.

Such experiences and inspiration make Lawrence’s drive for excellence seemingly quite unstoppable. He credits Melsa Buxton, his first headteacher as an NQT, with emphasising the importance of being “highly ambitious, driven and aspirational” for pupils with special educational needs.

When he took his second headship, at St Giles in 2015, he was determined the school should reach the top and introduced three new curriculum drivers: communication, independence and community.

When a pupil’s EHCP arrives, staff approach it with those three goals in mind, he explains: vastly increasing a pupil’s communication abilities, their capacity to work independently towards an adult life, and building a sense of community in which pupils are engaged and happy. A big outdoor education programme was launched to help meet all three goals, so that now every classroom has its own outdoor area. Pupils learn to use saws and hammers, make fires and build dens.

It was in 2016 that inspectors came to check if the school still deserved its ‘good’ grade. They said it did. “But we wanted absolute clarity on why it wasn’t outstanding. It was bouncing to and fro all day,” laughs Lawrence. Inspectors looked at more evidence and agreed to convert the inspection into a two-day visit. That afternoon, they told Lawrence the news – the school was ‘outstanding’.

“I said, ‘Can I just nip to the loo?’ And I legged down the corridor into the staff room and shouted, ‘WE’VE DONE IT!’ and we were all going mad,” cackles Lawrence. “Then I said, the inspector thinks I’m in the toilet, so I ran back and composed myself.”

Since then, the school has won SEN School of the Year at Pearson’s Shine a Light Awards in 2019 and achieved “world-class school” status, a quality mark that looks at the development of pupils’ qualities and characteristics, instead of national assessment frameworks. Meanwhile, the school delivers inclusion and SEND training to about 40 schools, sharing best practice in mainstream settings.

I said, ‘Can I just nip to the loo?’ And I legged down the corridor into the staff room and shouted, ‘WE’VE DONE IT!’

“It’s still quite unique for special schools to be seen to be leading the way,” says Lawrence. “We have to shout a lot.”

But it’s working. As we speak, Lawrence’s phone rings. He puts it down after a moment. “That was the DfE.” He’s going to be part of an ‘inspirational headteachers’ series.

Perhaps finally special needs schools like his, and special needs heads like him, will get the full recognition they deserve.

Your thoughts