Nadine Bernard, headteacher at Van Gogh primary school, landed her first headship at one of the most infamous academy controversies. She talks to Jess Staufenberg about facing down ghosts of the past…

For Nadine Bernard, letting go of feelings of shame or inadequacy has been at the core of getting to where she is now.

Bernard is in her first headship, at a school with perhaps one of the most infamous histories in recent English education.

The former Durand Academy, now re-branded as Van Gogh primary school, began its rapid collapse into controversy in 2014. A National Audit Office investigation revealed that then-headteacher Sir Greg Martin had topped up his already generous salary to more than £400,000 via management fees for the public’s use of leisure facilities on the school’s site.

The five-school Dunraven Educational Trust then took over Durand Academy, which reopened under its new name in the summer of 2018. Bernard arrived the following year and, after a brief maternity leave, has just completed her first full year.

There are still a few legal wrangles left for the school over premises, but Bernard is letting nothing bother her, and is determinedly future-facing.

Last week she won a Fair Education Alliance “innovation and intrapreneurship” award for her Aspiring Heads initiative. The organisation aims to equip black teachers with the “resilience, skills and mindset to secure leadership roles”.

Bernard has previously struggled to shake off feelings of inadequacy herself. “I would say in terms of my childhood memories, I am a child who actually lacked a lot of confidence, due to significant traumas that happened to me. It took me time to find my place in the world, to feel I am valuable and deserving.” She doesn’t wish to share details, but says she often shares the story privately if she “knows it will help someone else”.

Her ensuing lack of confidence also led to her being bullied in primary school, which was in East Dulwich in London. For her, school was not always somewhere that built her confidence back up.

“I remember one teacher in particular just used to do an ‘X’ across my whole page. That, with everything else I was experiencing, continued to reinforce I wasn’t good enough.”

Bernard also recalls standing with her mother in the school office, and overhearing a member of staff say “you shouldn’t have put her down for that secondary school”, indicating she wouldn’t cope in an academic environment. “My mum said, ‘that school is going down on that piece of paper. My daughter is more than capable.’”

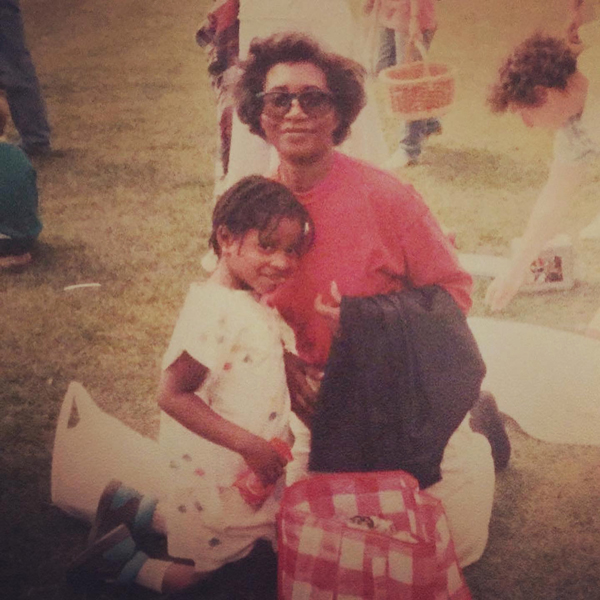

Bernard describes her mother, Isoline, as her guiding star: a woman, who having travelled to a new country from Jamaica, was determined to get the best for her daughter. Time and again, she fought for her.

Now Bernard’s past classroom struggles have underpinned her approach to tackling a school with its own sense of historical shame.

She reflects on changes she has since introduced: “From what I understand, children would walk through corridors in complete silence. But actually, I want to create children who don’t do things out of fear, but out of an awareness and understanding that, ‘actually, this is a good thing to do’.”

She’s always been cautious about “behaviour policies that are about reprimanding children and throwing out consequences for behaviour”.

“As a child, there are certain things we cannot expect them to know. Children come from different backgrounds, different circumstances, and some children for example will have a better understanding of what sharing looks like than others. So I see it more as training children to be their best self.”

Bernard doesn’t expect children to conduct themselves perfectly after being told an ‘expectation’, because she believes habits change over time. “I think a lot of times schools can expect: ‘I’ve told you once, I’ve told you twice, I’ve told you 10 times’, but there’s something important we need to understand about practice.”

She adds: “Everyone deserves to be respected. I know how it feels not to be respected, and that doesn’t allow someone to show their best self.”

The same drive explains why she has placed character-building at the centre of her school improvement strategy at Van Gogh primary. Durand Academy was graded ‘inadequate’ in all categories in 2016, and as a new school is now awaiting inspection. “That was very, very important to me,” she says. “It’s all about developing self, and the skills that you need to interact well with others and lead yourself well.”

As a once-shy child, Bernard is also committed to reducing passivity in her pupils, instead building their skills as speakers and in turn raising their self-confidence. An example is the introduction of “effective maths”, in which pupils discuss maths sequences together.

“They take turns. Before, all that dialogue was potentially being missed, because it was so much about the teacher talking. We want children to do more of the thinking, because when you think, that’s when you learn.”

Building confidence and overcoming barriers was a large part of Bernard’s story in adulthood, too. In her last year at Roehampton University, where she studied primary education, she found out she was dyslexic. “It was such an epiphany moment that explained so much. But I also thought, ‘wow, Nadine, you’ve developed your own way of working without those fundamental supports’.”

Bernard also had to face down a damaging lack of expectation within the education system. She recalls a visit from an Ofsted inspector in the last five years. “When I welcomed them into my school, they looked at me and said in a discrediting tone, ‘you’re the head?’”

She continues steadily: “I’ve had innocent comments about how I would potentially look more professional with my hair straight. I’ve had my skin touched and stroked or people touching my hair. I also remember being told to think carefully about what name to give my son.”

They looked at me and said in a discrediting tone, ‘you’re the head?’”

Of the controversial report from the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, published in March, Bernard says: “We can’t keep shutting the issue of racism down, because that way you can never make a difference. It can feel like we make 10 steps forward, then 20 steps back. It becomes tiring, exhausting.”

But during it all, her mum’s voice telling her “never to be ashamed” rings in her ears. She’s also discovered “real champions” among white colleagues too, pointing to Liz Robinson at the Big Education academy trust as “like a sister” to her.

And so, after George Floyd’s terrible murder last year, Bernard set up Aspiring Heads, an online leadership development programme for black teachers (she points out that she cannot claim to have expertise in the experiences of all minority ethnicities, and they should not be lumped together).

“I’m not a whinger, I’m solution-focused,” Bernard smiles. She runs a monthly webinar with each of her teacher students, introducing them to a different black education leader and working through six leadership ‘competencies’.

Students complete modules online with an accompanying podcast recorded by Bernard and her husband Ethan. Now, the pair have won £15,000 through the FEA award. This month, Ethan left his job as a youth worker to run the project behind the scenes full-time.

It brought a sense of “liberation”, says Bernard. “It feels like I’ve been through a lot, and a lot that I feel many people around me are totally unaware of. People don’t see the many times I’ve had to pick myself up, to find my confidence when it could easily have been crippled. This recognises something I’ve invested so much time and energy into.”

In the middle of next month, there will even be an Aspiring Heads leadership summit. It’s subtitled: “Overcoming, Preparing, Moving Forward”.

It’s Bernard’s philosophy. And it perfectly suits the troubled history of a school like Van Gogh primary – a history she is determined to leave far behind.

Your thoughts