The government is concerned that 64 academy trusts are stockpiling cash by sitting on reserves of up to 140 per cent of their annual income.

But no action has been taken in any case, with most trusts saying the money has been built up to fund construction projects or to shield their schools from financial uncertainties.

One trust has invested most of its reserves into high-interest gilts, with earnings now funding central team staff.

With school budgets coming under increasing pressure, the findings have reignited debate about what level of school reserves should be deemed appropriate.

Andrew Pilmore, of DRB Schools and Academies Services, warned leaders were “caught in a trap of being very cautious as they don’t know what’s round the corner” politically and financially.

“If you want schools to be willing to spend their surpluses, they need to be secure. If they don’t do that then in three, four years, they’ve got a financial notice to improve for having very low reserves – it only takes a couple of big issues.”

The trusts with huge reserves

The Department for Education released “good practice” guidance on academy trust reserves in 2023 after the National Audit Office (NAO) ordered officials to investigate those building up “substantial sums”.

The guidance states a high level of reserves equates to “20 per cent of income or above”. The NAO found 22 per cent of trusts met this threshold in 2019-20.

Government policy is to contact those with “high levels” of reserves to seek reassurances.

Last year, the first crackdown since the new guidance, the DfE wrote to 64 trusts. The letters were based on information from 2022-23.

Data obtained through freedom of information shows 13 were sitting on reserves that equated to more than 40 per cent of their annual income.

“To have very high reserves is almost as bad as having no reserves,” said Micon Metcalfe, a school finance expert.

“Most school income is to be spent in the year in which it’s allocated, so if reserves have got very large, the question is: are the resources being spent effectively for the education of those children?”

Reserves at 140% of income

Schools Week analysis suggests Ashton West End Primary Academy in Tameside had the highest level of reserves, with £3.9 million savings representing 140 per cent of income.

Accounts show it anticipated allocating part of this “over the next three years to maintaining educational standards throughout the academy, including appropriate staffing levels and to renewing parts of the… infrastructure”.

What’s left “will be held as the contingency and to support future strategies and initiatives… and mitigate against future risks including diminishing funding levels”.

It was followed by The Specialist Education Trust (121 per cent), the only other trust in which reserves were higher than income.

Projected five-year budgets for the Slough-based SAT “show a need to hold reserves… as funding becomes tighter and staffing costs increase through pay rises, increased [National Insurance] costs and increased pension contributions together with inflationary pressures”.

It might also use the money to meet “unforeseen costs, such as repairs, maintenance, or essential equipment replacement… without disrupting educational services”.

Analysis suggests Ashton West End’s and the Specialist Education Trust’s reserves fell in 2023-24.

‘This money isn’t just sitting around’

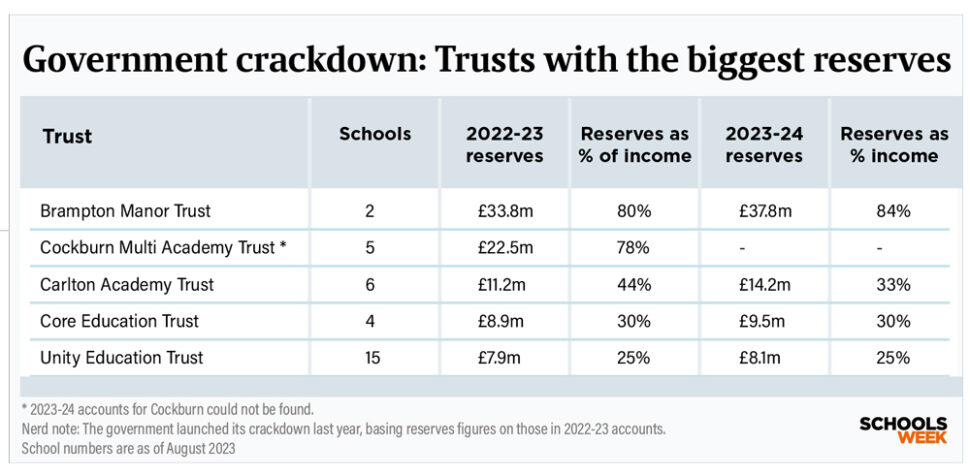

Three of the trusts contacted by the DfE were sitting on reserves of more than £10 million. Brampton Manor in east London had £33.8 million in 2022-23, equalling 80 per cent of its total income. This was the highest amount of any trust – and reserves rose last year.

The trust – which runs two academies – did not respond to our requests for comment. But it did concede in accounts “these reserves may appear high”, but “are not excessive and are necessary in the light of the uncertainty in funding”.

Cockburn Multi Academy Trust in Leeds and the Bradford-based Carlton Academy Trust held £22.5 million and £11.2 million respectively.

Cockburn said its reserves were being used “strategically to build long-term resilience, improve educational opportunities, and foster sustainable growth across its schools”.

Carlton’s rose to £14.2 million in 2023-24. Adrian Kneeshaw, its chief executive, said about £12 million had since been invested in long-term gilts – government bonds perceived to be “low-risk” investments.

He expected to deliver a return of about £570,000 a year on the investment.

“The money’s not just sitting around. We use that annual return to fund a substantially expanded central services team – for example, we recruited three secondary subject directors.”

Trusts are allowed to invest cash as long as they have a policy and ensure “security of funds takes precedence over revenue maximisation”.

A report by the Kreston group of accountancy firms this year showed trusts now generate £26 per pupil, on average, through investment, up from £7 per pupil a year earlier.

This comes as “many” trusts with “significant” savings start to “deplete them, some… at quite a rapid rate”, said Andi Brown of the academy consultancy SAAF Education.

Dire capital cash necessities higher reserves

The government said “around 90 per cent of trusts hold reserves of at least 5 per cent of total income”. But they have “the flexibility to maintain a level of reserves that trustees decide is appropriate”.

High level of reserves could be down to “specific needs – for example, upcoming contributions to capital projects”, they added.

However, it would be “unusual and potentially hard… to justify the decision to hold significant reserves at this level for general cashflow contingency, given this funding could be used sooner for the benefit of pupils”.

Unity Education Trust said its £8.1 million reserves will fund refurbishment at its AP sites over the next 18 months.

Once this is accounted for, its reserve levels were “less than 20 per cent” of income.

The Kreston report said reserves of 10 per cent were more appropriate given the inadequate access to government cash for capital projects,

The trusts that the government contacted on average ran 2.5 schools. More than half were single-academy trusts, while one had more than 10 schools.

Phil Reynolds, of the audit firm PLR Advisory, said the smaller the trust the greater the risk of collapse. “All it takes is one of your schools to go a bit wrong and that will have a massive impact. You’re going to have a mindset of being ultra-cautious with your budgeting.”

Reserves ‘expected to decline’

Adrian Packer, the chief executive of CORE Education Trust in Birmingham, said his organisation “inherited significant debt” after four of its academies joined from a “failing trust” in 2018.

The MAT had “reserves in place for any further unforeseen costs of which there have been several already”.

These were “expected to decline over the next few years as we reinvest in our schools and facilities to ensure they are fit for purpose”, he said.

Brown also said that “the fact we don’t always know about grants or the methodology behind them until late in the day makes it incredibly difficult to budget”.

The £1.5 million reserves of the small Michaela Community Schools Trust in north London equated to 25 per cent of income, according to our analysis.

Meanwhile, others need it to grow.

The Ambitious About Autism Schools Trust in London, where reserves were once just under 70 per cent of income, has been expanding. Reserves “fund new developments, [provide] working capital and [help] to manage risk”, said Paul Breckell, its deputy chief executive.

Its reserves have since fallen to 57 per cent of income and will keep falling “in a managed way as we invest in growth”.

Are councils clawing back excesses?

While it’s not possible to compare individual schools with trusts, latest government figures show authority-maintained school reserves represented 7 per cent of total income, on average, last year.

Just over half of council schools with surpluses had reserves deemed “excessive”. Thresholds for this are set locally by councils.

Schools in Slough had the highest level of reserves on average at 18 per cent.

Guidance produced by the authority said its officers would review schools’ plans for the cash if they exceeded a threshold of between 5 and 8 per cent. Amounts “not fully supported by evidence will be considered as potentially subject to clawback”.

An Education Policy Institute (EPI) study from 2019 showed more than half of excessive reserves in council schools were already committed to specific projects.

But if the “excess” was fully redistributed to schools in the red, then funding deficits would be wiped out in four-fifths of authorities.

Could surpluses be redistributed?

Jon Andrews, the EPI’s head of analysis, said it was not “unreasonable to consider whether money that’s there should be redistributed, though that’s not without policy challenges”.

Academy trusts are already able to do this, by pooling their schools’ general annual grant funding and redistributing it based on their own metrics.

DfE data suggests trusts were sitting on just under £4.6 billion in 2022-23. Eighty-seven per cent of chains were in an overall surplus, while just 2 per cent had slipped into the red.

The DfE confirmed no further action was required for any of the 64 trusts it engaged with over reserves.

It said the work “ensures trusts have plans in place to use their funds to deliver outcomes that benefit pupils … trusts are planning effectively to mitigate against unforeseen issues and are investing in their current and future pupils’ education”.

Your thoughts