Around half of schools start teaching GCSE content when pupils are still in year 9, while some teach the courses to pupils as young as 11, a major new survey of teachers suggests.

The National Foundation for Educational Research surveyed 1,678 teachers from 1,439 schools for its annual Teacher voice omnibus survey.

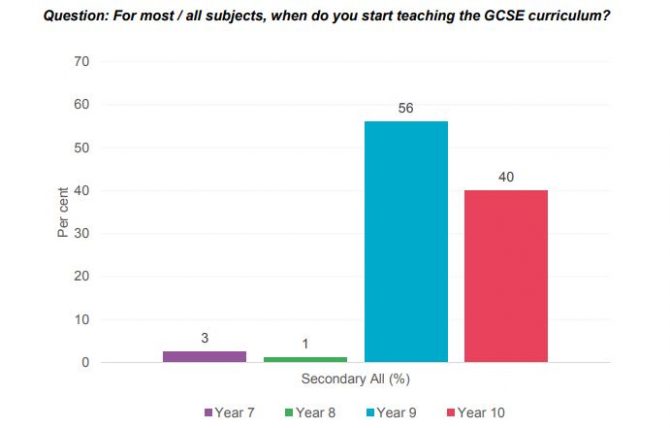

Fifty-six per cent of respondents said their school started teaching the GCSE curriculum for “most if not all” subjects in year 9, while a similar proportion, 53 per cent, said the number of GCSEs on offer at their school has been cut.

But some schools appear to be starting even earlier – 3 per cent of respondents said their school started teaching GCSE content in year 7.

The survey is not the first to highlight an apparent narrowing of the curriculum at schools across England, which leaders put down to new performance measures, such as Progress 8 and the EBacc. Government ministers and Ofsted chief inspector Amanda Spielman have warned against the practice.

Last year, the Department for Education’s own school snapshot survey found pupils in year 9 were expected to start studying for key stage 4 in all subjects in 35 per cent of schools.

NFER’s survey results have been published alongside the organisation’s response to the consultation on Ofsted’s proposed new inspection framework, which is set to come in to force in September. Under the proposals, Ofsted will increase its focus on ensuring schools teach a broad and balanced curriculum.

But according to the Teacher Voice Omnibus survey, only 68 per cent of staff agreed that their school offered a curriculum with “breadth and depth” at key stage 4, while 22 per cent said it wasn’t.

Accountability measures were cited as the most common reason for fewer GCSE subjects being offered, with 35 per cent claiming they were dropped because they “did not fit with Progress 8”. This factor was closely followed by staff shortages, which was cited as a reason by 32 per cent of respondents.

At key stage 3, a much higher proportion of staff – 81 per cent – testified that their curriculum had breadth and depth, further suggesting that breadth is lost when pupils move on to GCSEs

Under Ofsted’s proposals, schools will be inspected on the intent, implementation and impact of their curriculum design, with a move away from focusing on pupil outcomes and data.

But NFER warned today that the shift away from data could make staff believe Ofsted is no longer interested in hard numbers.

As such “there is a risk that school leaders and teachers may stop using data to self-improve altogether, resulting in many good practices being lost”, said the NFER in its official response to Ofsted.

The survey showed 79 per cent of school leaders supplied internal data to Ofsted to provide “greater context about performance and outcomes”.

Ofsted should “develop guidelines for schools explaining how using appropriate data can help to drive improvements” in learning, and “provide examples of where this has been effective”, said the NFER.

The inspectorate could also provide examples where data has not added value, they added.

Carole Willis, chief executive , said she supported Ofsted’s efforts to ensure inspections don’t result in unhelpful data collection, but added “school leaders can and should be using proportionate data to manage their schools”.

“Ofsted will need to avoid sending an unintended signal that schools and teachers should not be using data at all to inform and improve their practice.”

There is a lot of anecdotal evidence that the teaching of the GCSE and A Level Computer Science qualifications continues to be phased out in many schools,. This is mainly for four reasons: 1) the difficulty recruiting properly qualified staff, 2) the difficulty (perceived or otherwise) of the courses compared to other courses and the need to focus on the traditional eBacc subjects 3) the serious money that can be saved by cash-strapped schools not running these courses and 4) the incompetent handling of the highly predictable coursework problems and the damage to the image of the subject.

Only 18 months ago, the Royal Society were shocked to find over half of schools didn’t offer this subject, even though it was an eBacc subject, and this situation appears to be getting worse. Little of the £80 million for “training” has since materialised. There is a suspicious lack of transparency over what this money is being used for, dates, deadlines, targets, how resources are being sourced and tendered for, who will actually do the training and the tendering of the process and so on.

The direction that correcting the problems in this subject are going in and the lack of monitored and accountable progress is a growing concern for many of us watching. There has been a lamentable lack of teacher involvement in this process. Computer Science is just another sub-story in this article of the way the subject is declining, when it ought to be the most popular subject in schools in this day and age! A serious overhaul of those running the show is needed to stop this subject going down the drain, and quickly.

This is a consequence of the ‘knowledge-based’ learning fallacy. Genuine attainment in terms of deep understanding, rather than cramming to pass crude exams, has always been driven by cognitive ability. KS3 is when cognitive ability/general intelligence can be readily enhanced by the right kind of developmental teaching and learning as explained here.

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2018/09/22/definitive-research-that-shows-teaching-for-cognitive-development-can-permanently-raise-general-intelligence-in-pupils-of-all-abilities/

Rote learning and condemning pupils to memorise stuff they don’t understand makes them less curious, dimmer and much more likely to become alienated from schooling altogether.

Starting KS4 in KS3 is therefore a REALLY BAD IDEA. The schools that do it think it will improve their GCSE results. Even if it did (which is unlikely) it will wipe out recruitment to hard A Levels like maths and the STEM subjects.

You would expect OfSTED inspectors that know anything about education to understand this and discourage it. Some chance.

Like all potentially lucrative and career enhancing vocational courses/subjects there is a danger that course content if targeted too narrowly will only appeal to those who are dedicated to the subject. Computer Science being deemed as the ‘new science’ by the incumbent secretary of state fell into this predicament. This was a lost opportunity to develop a general understanding of the digital world, instead it focused heavily on coding, a great turn off for many and of little interest/use for those not intent in studying the topic further. I refer you to my paper on the problems of recruiting Computer Scientists into the teaching profession at https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8324213

Key Stage 3 should be a time for discovery for young people to enable them to be able to make informed choices when the time comes to specialise their education, such as GCSE, ‘A’ level, BTEC decisions. There is a whole life time for learning, we should not be attempting to lead a young persons educational journey by forcing them make crossroad decisions too early. If OFSTED is serious about monitoring schools’ curriculum entitlement then it should judge a curriculum by breadth and eliminate the performance monitoring of EBAC. This would reduce the tension that schools are facing and allow those schools that are dedicated to enhancing the life chances of low socio-economic children to prepare them for life in their local communities, by providing relevant courses and qualifications, notwithstanding STEM opportunities, that are recognised by employers.