The Department for Education has been told to take “swift action” to review its response to the covid-19 pandemic to ensure poorer pupils don’t miss out again.

A National Audit Office report into how children were supported during the early stages of the pandemic has highlighted several flaws in the department’s response (see key findings below).

Meg Hillier MP, chair of the committee of public accounts, said the DfE’s lack of contingency plan meant its reaction was “slower and less effective” than it could have been.

“DfE’s failure to do its homework has come at the expense of children – and has hit those who were already disadvantaged the hardest,” she added.

The NAO said it was “crucial” the department now takes “swift and effective” action to learn wider lessons and ensure the catch-up programme is effective.

Hiller added this will ensure “its support is properly targeted to prevent the gap between disadvantaged children and their peers from widening even further”.

But the DfE said it acted “swiftly” at “every turn” to help minimise the impact on pupils’ education and provide “extensive support”. They are considering the NAO’s recommendations.

We look at the report’s key findings…

1. DfE had no plan for managing mass school disruption

The NAO found the DfE did not have a pre-existing plan for managing “mass disruption” to schooling on the scale caused by covid. Instead, they activated emergency plans for managing local disruption, such as flooding, in January last year.

It was only at the end of June the DfE began to develop a plan setting out “objectives, milestones and risks at a departmental level”. The NAO said the response was “largely reactive”.

The DfE also put schools under pressure by publishing large amounts of guidance, often without clarity on what had been updated and sometimes late in the evening. A Schools Week investigation last year found a quarter of guidance changes were issued during anti-social hours.

Between mid-March and April 28 alone, DfE published more than 150 new documents and updates to existing material.

2. ‘Lack of details’ over NTP provider’s management fees

The contract to run the government’s flagship National Tutoring Programme “lacked detail” including around what management fee the Education Endowment Foundation, which runs the scheme, would take.

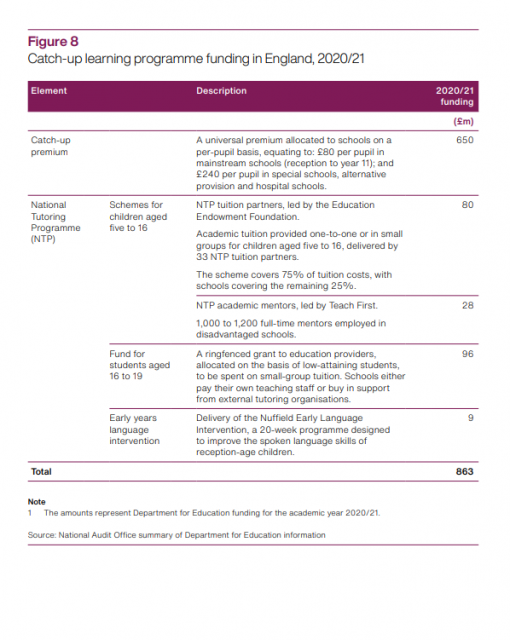

The EEF had been given £80m to run the tuition arm of the programme, and was appointment through a “variation of its existing grant” with the DfE.

The NAO reports reveals a review for the DfE’s audit and risk committee in October noted that variation “lacked detail” on how EEF would allocate the tuition partners budget “including what proportion it would take as a management fee”.

The review also noted that, without competitive procurement and direct involvement in selecting tutoring providers, it was difficult for the DfE to guarantee “value for money”.

But the DfE took steps to mitigate these risks, including establishing regular performance reporting on take-up and expenditure and a delivery board to oversee the schemes, the report said.

EEF’s grant conditions stipulate that it must ensure approved tuition partners are paid no more than market rate.

The DfE also plans run tenders for future years and has commissioned an independent evaluation.

3. Questions over tutor scheme’s poor pupil reach …

As Schools Week reported last week, the DfE did not stipulate a target number of pupil premium children to be reached this year through the flagship National Tutoring Programme.

The NAO said 125,200 children have been allocated a tutoring place across 3,984 schools – despite the government to aiming to reach between 200,000 and 250,000 youngsters.

Just 44 per cent of the 41,100 who had started to receive tuition were eligible for pupil premium.

“This raises questions over the extent to which the scheme will reach the most disadvantaged children,” the report adds.

When asked why two thirds of pupils had still not started tutoring, the NTP said the percentage has since gone up but would not provide the figures.

DfE expects at least 65 per cent of tutoring next year to be provided to pupil premium children.

4. … and demand for mentors ‘outstripped supply’

Demand also “outstripped supply” for the academic mentors arm of the tutoring scheme, run by Teach First.

As of January, Teach First had received requests for mentors from 1,789 eligible schools. By February, it had placed mentors in 1,100 schools – more than it’s 1,000 target but still way short of demand.

The government is aiming to place 3,600 academic mentors in schools next year.

5. Fifth of catch-up funding taken from other budgets

The report also reveals how only 80 per cent of the £1billion catch-up funding announced last year was additional money from the Treasury. The DfE took 20 per cent from “other budgets”, the report says, however it does not state which areas.

The DfE said today that the “majority” of its contribution came from “natural savings” across the year, rather than reductions elsewhere.

The government has kept quiet over why £140 million of the promised £350 million to run the NTP this year remained unspent, as revealed by Schools Week. The underspend has now been rolled over to run the scheme next year.

The report reveals the DfE decided it could not “scale up” the NTP schemes faster without “jeopardising delivery and quality of provision”.

6. DfE snubbed £42m of Covid cost claims

As of January, the department had paid, or intended to pay, schools £133 million of the £181 million they had claimed for exceptional covid-19 costs, between March and July last year.

The NAO said that within the £181 million total, schools made £42million claims outside these categories. The cash came with tight restrictions, with things like personal protective equipment costs, additional staff and technology for children’s home learning not included.

7. Covid helpline fell over at height of pandemic

The report reveals that in the week of March 16, there were 17,900 calls to the DfE’s covid helpline – an average of almost 3,600 per day.

Callers abandoned 55 per cent of calls and the average waiting time was 35 minutes.

A week late, the DfE increased the number of advisors staffing the helpline from around 90 to 300, which saw the waiting time drop to less than five seconds.

8. DfE massively scaled down early laptop rollout

The NAO said that in early April, the DfE considered providing laptops or tablets and 4G routers for vulnerable children and those in all “priority groups” who did not have access.

This would have involved providing 602,000 devices and 100,000 routers. But due to the “practical difficulty” of supplying devices on this scale, the DfE reduced the numbers.

Instead, devices were issued to children with a social worker, care leavers and disadvantaged pupils in year 10 only – estimated to be about 220,000 devices and 50,000 routers. The DfE has now issued nearly 1.3 million laptops.

Your thoughts