Two years after its rebrokering, Van Gogh primary in south London is still struggling to move on from its association with Durand Academy

It’s been almost two years since Durand Academy closed its doors for the last time, its funding agreement with the government torn up and its leaders ordered to return the school’s land and buildings to Lambeth council. But as Van Gogh Primary School, Durand’s successor, prepares to welcome its third intake of reception pupils, the shadow of its scandal-hit previous incarnation still hangs over it like a dark cloud.

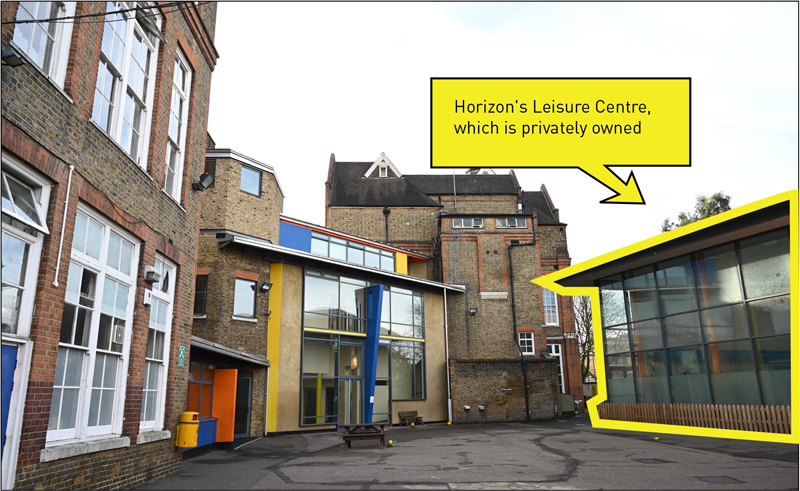

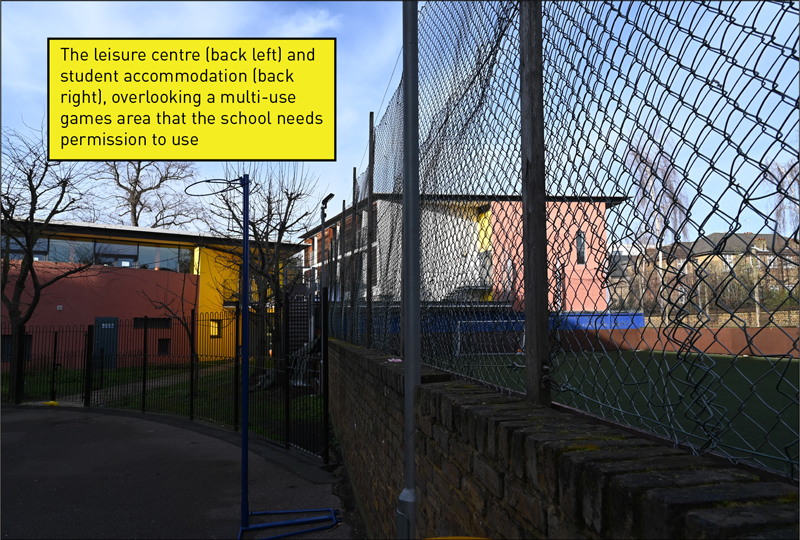

Set across two sites in Lambeth, south London, Van Gogh looks like an ordinary inner-city primary school, with huge windows set in towering Victorian redbrick buildings on an otherwise residential street. It’s not until you go inside the school’s Hackford Road site – as I did earlier this year – that you realise how out of the ordinary it is. Peppered across the site are facilities pupils cannot use and to which staff have no access. Metres from its back door, across the tiny strip of land that makes up the site’s only outdoor playing space, sits Horizon’s Leisure Centre. Next to it, and on the top floor of one of Durand’s buildings, are private flats run by London Horizons, including student accommodation.

When Durand became an academy in 2010, it gifted these facilities – worth £15 million according to the National Audit Office (NAO) – to the Durand Education Trust, a private firm established by the school’s then leaders. During the academy’s heyday, the private firm funnelled money made by subsidiary London Horizons Limited into the school, and pupils had free access to the leisure centre. But with Durand Academy Trust all but wound up, that agreement is defunct. If Van Gogh’s pupils want to swim in the pool on their site, their school has to pay.

A 2014 NAO investigation revealed a complex web of organisations revolving around the school, with large sums of money flowing in all directions. But the detail that caught the eye of MPs, the public and press was the annual earnings of Sir Greg Martin, the school’s former executive head and one of those who built the leisure facilities. At one point, he earned more than £400,000 a year from a combination of his generous salary – which made him one of the highest-paid executive heads in the country – and management fees from the leisure centre.

Following a particularly gruelling public accounts committee hearing in 2015, Martin claimed the success of the school was “underpinned” by the private investment income received from London Horizons Limited. But in the end, the scandal strained the Durand brand too far. Within a few years, a man once known as Michael Gove’s favourite headteacher had retired (albeit to immediately become the school’s chair of governors), and the government had moved to rebroker the school to a new sponsor.

David Boyle, chief executive of the Dunraven Educational Trust, which took on the school and reopened it as Van Gogh in 2018, acknowledges that under Martin, the school had been “transformed from where it had been originally”. An Ofsted report from 2008 branded the school ‘outstanding’ and praised “innovative developments” of its buildings as evidence of “vision and drive”. It was rated ‘good’ in 2013, after its first inspection since becoming an academy in 2010.

“[Martin] was very open when I met him,” says Boyle. “His view was that if he was in the independent sector, if he was working in business, he could make a lot of money for doing this kind of transformative job, so why shouldn’t he be able to earn it in the state education sector?”

There was no free play, and there was a tiny triangle of concrete outside

The initial furore over the school now seems like a distant memory, but Durand’s complicated legal structure still plagues the setting that now operates in its place. Although the school buildings were handed over in 2018, the commercial side of the premises remains under Durand Education Trust’s control.

Following a second direction issued by the Department for Education, the company was supposed to hand them back by the end of March. But the DfE confirmed this week that it has not yet done so. “All parties continue to work towards the transfer of the commercial land, in accordance with the second direction issued to Durand Education Trust,” a spokesperson said.

A spokesperson for Durand Education Trust said it was “ready and willing” to hand over the commercial land, but was waiting for the completion of a temporary underlease agreement with Dunraven, which would see it rent the leisure and accommodation facilities back from the school until a permanent operator is found.

The trust has also secured a Court of Appeal hearing in November over the matter of compensation for the land “which would potentially find Lambeth [council] having to pay many millions”, the spokesperson said.

“DET has had to push this, because the Charity Commission has repeatedly said that we cannot give the land back without compensation. The ball is in Lambeth’s court.

“The secretary of state has acted outside his powers. We accept he has the power to order the transfer of the land. What we would never accept is that he can order it without compensation.”

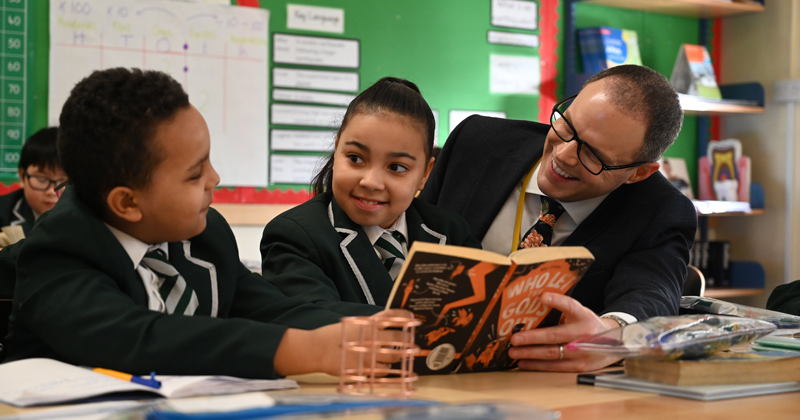

As the battle over the school’s land has raged on behind the scenes, Van Gogh’s new leadership team has spent the best part of two years trying to move the school on to its next chapter. The mezzanine floors and small classrooms that characterised Durand’s former incarnation are gone. In their place, children learn in bright, airy rooms. A new outdoor area has been created for nursery and reception children who attend the nearby Mostyn site.

“It was run like a prep school, so most classes had around 15 children in them. But that cannot be financially viable in the ‘real’ world,” says Paul Robinson, a consultant head brought in by Dunraven to oversee the transition. “Children in nursery and reception sat on high chairs at tables doing colouring in and handwriting. There was no free play, and there was a tiny triangle of concrete outside.”

The children didn’t seem to benefit, given the extra money available

The atmosphere on the early years site could not be more different now. Even in February, children run between their buzzing, colourful classrooms and a shared outdoor space filled with sandpits and games. They run up to Robinson to say hello, demanding to know where Meryl is (his dog, who often comes into school with him).

The school has also moved from a compliance behaviour policy to one of self-reliance, says Robinson. “We had to teach children to self-regulate, and that was a massive shift. Children were streamed from year 2, and they were in these small classes. You can easily make 15 children comply. But when you’ve got 30 children who are all mixed-ability, mixed-needs, suddenly it’s like ‘oh my goodness we need to get this sorted out’.”

Despite the changes, everywhere are reminders of the hybrid nature of the school’s site. In one upstairs classroom, a waste-water pipe from the flats above runs along the ceiling. At the top of one staircase, there is a fire escape for the private accommodation.

The school’s buildings have also had to be refurbished. “This school was physically run into the ground,” says Robinson. “Most of the classrooms, we’ve had to repaint, put in new lights. We’ve had to replace the windows. New blinds. New flooring. I’m also obsessed about the mismatch of doors. Nothing matches.”

Boyle describes an “odd duality of the previous incarnation, which was in some ways all about money, all about presentation, all about how it appeared to the outside world. But on the inside, the children didn’t seem to benefit in the same way, given the extra money available”.

“There were mezzanines everywhere,” adds Boyle. “But not mezzanine as in stylish and sophisticated Manhattan loft apartments. As in, let’s create two rooms by putting a floor in the middle regardless of the experience for staff and children.” He recalls a hall with a “beautiful, highly-polished parquet floor”, but no displays on the walls. “There was nothing in here at all to stimulate learning. There was no library that we could see. There were no books for pleasure.”

Under the old Durand Academy model, Durand Academy Trust ran the school, while the Durand Education Trust ran the commercial facilities via London Horizons Limited. London Horizons then paid management fees to Martin’s own company, GMG Educational Support, but also donated all of its surpluses to the Durand Education Trust, which in turn made large donations to the academy trust.

Despite public outrage over these financial arrangements, the school maintained a strong support base in its community until the very end. Parents campaigned vociferously alongside Martin and his team against its closure.

This school was physically run into the ground

“They said ‘we’re doing a fantastic job, look at all the things we’ve done’,” Boyle says, “And to some extent that was true. They had done a wonderful job of providing things for the children in this school that weren’t there before. So things like the music, that they really invested in. The opportunity to have swimming lessons on both sites. That’s an amazing thing, and very rare in many schools, let alone state schools. And yet…”

When I catch up with Boyle and Robinson again in mid-June, the refurbishment is almost complete and pupils are beginning to return following the school’s partial closure during lockdown. But the lack of access to the commercial side of the site still seems a huge obstacle to the school’s development.

Boyle says he is grateful to the DfE and ESFA for their support “working with officers at Lambeth in resolving what has become an unnecessarily and increasingly complex matter for the benefit of the children at Van Gogh”.

“It would be very welcome to find that all parties involved were as equally committed to bringing about that resolution as quickly as possible so that the children at the school may benefit.”

Your thoughts