Teachers want help from professionals to tackle exclusions rather than undergoing more training, a new survey has found.

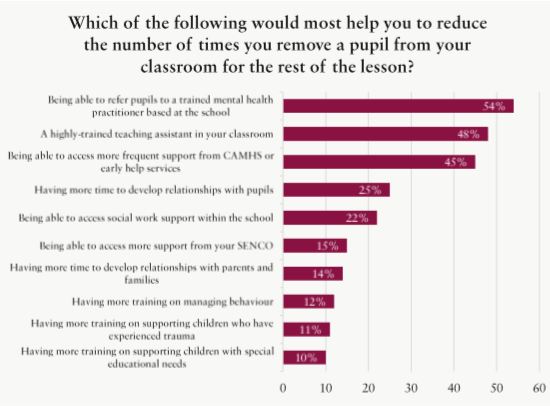

A survey of 1,500 teachers and school leaders for the Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and National Foundation for Educational Research shows half believe referring pupils to specialist mental health professionals and introducing classroom assistants would reduce the need to remove pupils from lessons.

But options involving more training were considerably less popular, despite the Department for Education’s plans for a £10 million behaviour network which will help support schools through staff training and updating sanctions and rewards schemes.

The report found only eight per cent of teachers believe schools are “too quick” to use official exclusions when there is another suitable approach, and 86 per cent believe being able to exclude is “essential to provide a good education for all pupils”. However, 79 per cent of all teachers also agreed that repeatedly being removed from lessons has a “detrimental impact” on learning.

More than half of classroom teachers said a highly-trained teaching assistant could reduce the number of pupils removed from class, but just one third of senior leaders said the same – a discrepancy the RSA said could be explained by “budgetary pressures”.

Of all teachers, 54 per cent said referring pupils to specialist mental health professionals would help reduce the need to remove pupils from lessons, while 45 per cent wanted to access more support from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services and early help professionals. The results for headteachers alone showed 70 per cent wanted more frequent support from CAMHS.

Laura Partridge, association director for education at the RSA, said the results show teachers “feel unable to support children at risk of exclusion on top of their existing workload pressures” and so are looking to other professionals for help.

However, options that involved more training proved unpopular, including training in managing behaviour (just 12 per cent of teachers favoured this), dealing with trauma (11 per cent) and special needs (10 per cent).

The report suggested this could be because teachers do not think they have enough time for training or think it would be good quality, or they “do not believe they should be responsible for providing these types of support”.

“Perhaps for understandable reasons, given the current teacher workload and pressures created by the accountability system to focus on exam results, teachers seemed to prefer responses to challenging pupil behaviour that involved removing the pupil from the classroom to being supported to prevent and respond to that behaviour themselves,” it said.

The survey showed 90 per cent of teachers felt it was justifiable to remove a child to reduce risk to other pupils’ safety and limit major disruption, while 77 per cent would remove a child from class to avoid “any disruption” to learning.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said the findings show schools need “better resourcing and support in tackling challenging behaviour” and currently have “limited resources” for early intervention and support.

Nansi Ellis, assistant general secretary of the National Education Union said teachers are “not experts in trauma or mental health” and called on the government to address the challenge of mental health provision and give “schools and society the services they need to help those in need”.

In May, the Timpson review into exclusions included proposals to review the reasons given for exclusions and ensure Ofsted properly recognises inclusive schools. Edward Timpson has said a new accountability system for excluded pupils should consider measures like attendance as well as the progress and outcomes of pupils.

The RSA said the number of pupils permanently excluded from school rose from just under 5,000 in 2013-14 to nearly 8,000 in 2017-18, averaging 42 pupils expelled every single school day. In 2017-18, 410,000 fixed-term exclusions were recorded, an 8 per cent rise on the year before and a 52 per cent increase since 2013-14.

A spokesperson for the Department for Education said it will “continue to back heads in using permanent exclusions as a last resort” and schools should be “safe and disciplined environments”.

Your thoughts