One of England’s first private finance initiative (PFI) schools struck a secret deal for taxpayers to cover a £1 million “bullet payment” to break free of its contract.

Schools Week analysis also suggests PFI owners of English schools could have recently made as much as £85.7 million in profits in a single year.

Shareholders could have pocketed as much as £48 million in 2023-24 alone, according to our research, extrapolated from the accounts of 71 companies running almost half England’s PFI school projects.

Meanwhile new documents show the firm overseeing the largest deal owed over £11 million to contractors when it collapsed. A row continues over repairs.

The revelations prompted calls for ministers to “hold providers to account in cases where large sums of public money have been spent on projects that are not fit for purpose”.

Schools Week investigates…

Trust’s ‘secret’ deal

Successive governments have used PFI since the 1990s.

Private firms build and maintain sites in exchange for mortgage-style payments, normally over 25 years, before buildings are handed over to taxpayers.

Barnhill Community High School in west London was one of the earliest school deals agreed, and the second to expire in 2024. Negotiations continued with Bellrock, its PFI operator, even after expiry, however.

The contract obliged the secondary to pay a £1 million “bullet payment” in monthly instalments to leave Bellrock as facilities manager – even after the main deal ended.

Ben Spinks, chief executive of the Middlesex Learning Partnership Trust which runs Barnhill, revealed the Department for Education had stepped in to cover it. They decided together not to tell Bellrock this, however.

“We didn’t want it to impact on the wider commercial negotiation that was still going on.”

Contract vagaries

Spinks had warned government it would have been a “very serious financial burden”, representing more than its “total pupil premium funding” over two years.

The case highlights “how complicated any PFI contract is and that some of the earlier ones were less tightly defined for both parties”, he said.

“There were times where vagaries in the contract made life difficult for [Bellrock] as well as us. There were certain matters on which the contract was just silent or not specific.”

Matthew Wolton, a partner at law firm VWV, said Tony Blair’s Labour government lacked “experience of these projects” when striking early deals.

“Some of the problems that we’re seeing now are because the first wave of contracts are not as good for the public sector as the contracts that came later.”

Stoke firm collapsed owing £11m

Stoke has 88 schools built under a PFI contract that ended in October with Transform Schools (Stoke) Ltd (TSSL). It is the largest school PFI deal nationwide.

Last year it was revealed some construction work could remain unfinished however, despite the council pumping in £3.5 million to fill a shortfall.

In December, TSSL went into liquidation. Company documents show it owed just over £11 million to 14 firms – some of which it was linked to – when it collapsed.

One creditor is recruiter 300 North. Paul Connolly, its CEO, said his firm is “going through the legal process of trying to recover the debt” of just under £21,000 after it “supplied a temporary worker onto the contract”.

A Stoke council spokesperson encouraged contractors to get in touch. They also stressed the authority intends “to complete the remaining works”, having retained around £8 million to do so.

Joint liquidator Jeremy Karr, of firm Begbies Traynor, said he will “seek the best possible outcome for creditors”. A “thorough review” of TSSL’s records will be conducted.

“We will also seek to comply with any reasonable requests from the council insofar as possible, with the assistance of the directors of the company, to assist the council in ensuring handover of warranties for school works carried out by subcontractors.”

Gaps in government data

Government financial secretary Spencer Livermore admitted last year the identities of many PFI firms are unknown.

He said there were 77 projects, with a combined public debt of £5.2 billion, where councils either “do not know who the equity holders are” or have not given the Treasury the data.

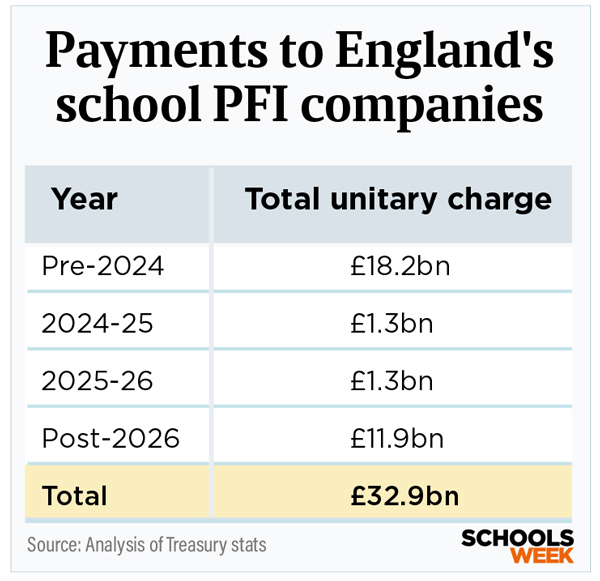

Schools Week analysis of the accounts of 71 PFI companies, each operating an English school contract, shows they received over £620 million in mortgage-style payments in 2023-24.

They reported combined profits of £35.6 million, while shareholders received almost £20m in dividends. The profits of many will come purely from PFI, though others may have other income sources.

The firms behind PFI

Part of a complex web of organisations, the 71 firms appear to be overseen by five larger investment companies. One of them is International Public Partnerships (INPP), which is responsible for 23 school contracts.

Amber Infrastructure, which advises INPP, said the companies are “focused on supporting the long-term stable operation of the schools and delivering critical infrastructure and sustainable value”.

“Private investors including INPP are not guaranteed a return when investing in social infrastructure PFI companies and are paid dividends only where circumstances allow.

“INPP’s own investors include those that benefit the wider public, such as pension funds and insurers.”

Another is Innisfree, which has 14 English school projects, including Stoke. Its website says it has provided “modern infrastructure to 260 schools with a combined capital value of £1.5 billion”.

The firm told MPs in 2011 it aims to achieve returns of 8 to 10 per cent every year for investors, mostly UK pension funds. It did not respond to requests for comment.

Dozens set to expire

So far, six PFI contracts have expired. Thirty-nine more will by 2030.

Jon Ward, estates director for an academy trust, said PFI does mean you “know the standard you’re supposed to be getting”, as it is written into contracts. But the challenge is “typically that could be more expensive”.

“Where it becomes difficult for some is the funding model has changed … with other financial burdens, so any margins you had you could be losing that in a PFI contract.”

In 2021, the Cabinet Office started running health checks on contracts set to expire within seven years, at which point authorities are told to start preparing.

Lost documents

Schools Week analysis two years ago showed just two of 41 councils assessed were deemed on track.

Speaking last year, Mark Fallows, of the DfE’s private finance team, said some authorities “have more resource and skillsets than others”. A number buy in support.

“On some of the projects, it’s been quite difficult to find all of the documentation. These contracts… are very complicated, but there probably, in a lot of cases, hasn’t been enough contract management.”

Despite this, the Treasury’s 10-year infrastructure strategy stated government “will work with the private sector to harness the potential for private finance”.

PFI is a form of public-private partnership, and the Treasury said it will keep using these where “value for money for taxpayers can be secured”.

Union’s ‘deep concern’

Julia Harnden, of the Association of School and College Leaders, argued it is “deeply concerning that, for a variety of reasons, so many schools with PFI contracts are in very difficult positions financially”.

“The government must continue to support schools with PFI contracts who have been negatively affected through no fault of their own, and ensure they are not left to carry this burden on their own.

“We would also like to see more done to hold providers to account in cases where large sums of public money have been spent on projects that are not fit for purpose.”

However, Wolton said that the fact “contractors and their lenders would be able to make a profit” was one of the key principles of PFI. Without this, they “wouldn’t get involved”.

“In later contracts, PFI contractors were incentivised to make savings (which would generate higher profits) on the basis that a proportion of these savings would be shared with the public sector, which would lower the overall cost.”

Your thoughts