More than a thousand schools with poor outcomes slipped through the net of the government’s RISE low-attainment crackdown, exposing a “significant gap” in its latest bid to boost results.

The Department for Education (DfE) approached thousands of schools in England with the worst attainment rates, urging them to seek support from the government’s regional improvement for standards and excellence (RISE) programme’s universal arm.

But hundreds more escaped the glare of officials because they were too small, Schools Week can reveal, despite registering some of the poorest outcomes in the country.

Reacting to the revelation, National Governance Association deputy CEO Sam Henson said: “Over a thousand schools appearing to fall through the cracks isn’t a data technicality – it’s a significant gap in the programme.

“Schools and boards that need support shouldn’t miss out simply because of their size.”

Hundreds slip net

On Friday, Tim Coulson, head of the DfE’s regions group, wrote to responsible bodies for the 2,092 schools in the lowest 25 per cent for outcomes at key stages 2 and 4.

He contacted the leaders to “remind” them of the support available through the universal RISE programme, telling them to “please consider” accessing it.

Only those who fell below attainment thresholds for all pupils and disadvantaged children received the correspondence.

But FFT Education Datalab analysis, exclusively shared with Schools Week, suggests that 1,063 poorly-performing primaries escaped scrutiny.

All were in the bottom 25 per cent for overall reading, writing and maths but, because they had so few children, data for their disadvantaged cohort was not published. This meant they fell outside the remit of the crackdown.

A DfE spokesperson stressed that the figures “for schools where pupil numbers are low [are] not published to protect individual privacy”. This is why they “were excluded from the analysis that informed the list of schools that were sent letters”.

“We are clear that all schools can engage with the universal RISE offer, which has been designed with all types of schools in mind,” the spokesperson continued.

Schools with small pupil cohorts tend to experience more extreme fluctuations in results year to year. However, disadvantaged children tend to receive lower grades.

Research by the Education Policy Institute found that poorer pupils ended secondary school 19 months behind their peers in terms of attainment.

‘Schoolboy error’

One academy trust CEO, who asked to remain anonymous, accused the department of making a “schoolboy error”. Two of his schools received the letters.

“You wouldn’t expect people to have slipped the net through a technicality. We just want a level playing field,” the trust chief said.

“They need to focus on all organisations. Let’s face it, sometimes, because you are under scrutiny, it does push you into a different gear to improve at pace.”

Henson added that the omissions show “the full potential of RISE is still to be realised”.

Describing these as “reparable flaws”, he urged the government to act “urgently to ensure the signals that prompt improvement conversations actually reach the boards who need them”.

Schools targeted

The analysis suggests that 61 per cent of the schools which received Coulson’s letter were run by an academy trust, with the rest under local authority oversight. Nationally, 55 per cent are in a trust.

United Learning has 11 academies within the scope of the crackdown. A spokesperson for the 95-school chain said: “The reality is that we are by some distance the biggest trust and we continue to take on a significant number of schools in challenging circumstances, many of which failed in the past.

“We are proud of our record of significantly raising attainment, which we continue to do.”

Regional disparities

Six more MATs had at least nine academies which received a letter. One of these was the Kemnal Academies Trust, which had 10.

Russell Hobby, its CEO, said the schools have been in the MAT “for a while” and that they “all serve areas of very high deprivation and often multiple overlapping issues”.

Some of the areas have “very weak employment prospects” and have been “neglected in terms of public services”. But he said this was “not an excuse – there are also schools who serve similar communities who haven’t received letters”.

“There have been good years and bad years [at these schools], and the job is to be more consistent,” Hobby explained.

“None of us think we’re producing the outcomes these communities deserve yet. But they will with the trust’s support.”

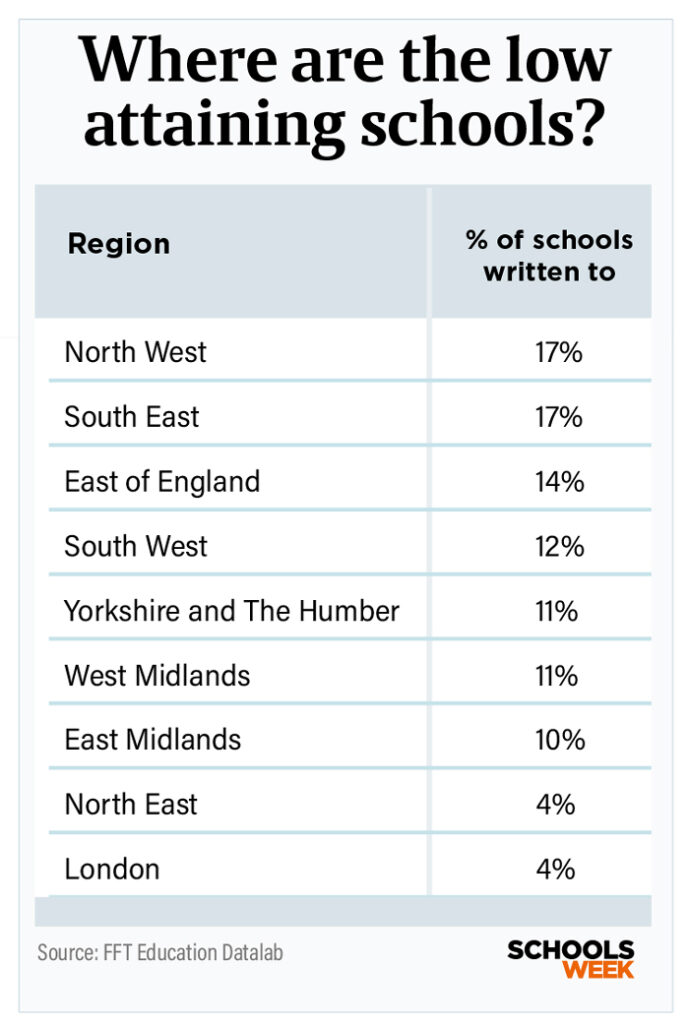

Datalab’s findings show the South-east and North-west accounted for the most low-attaining schools (both 17 per cent). Meanwhile, London and the North-east had the fewest (both 4 per cent).

The findings also suggest that the government push disproportionately targeted more deprived schools as well as those with historically lower-attaining intakes.

A ‘reminder’

The RISE scheme was launched last year, with its teams of “advisers” – leaders seconded to work alongside officials – tasked with intervening in so-called “stuck” schools.

David Carter, the former national schools commissioner, said the advisers “appear to be a very mixed bag”. He said the role “appears to be a smooth flightpath to retirement where making a difference would be a nice bonus”.

Universal support was later launched to “help every school improve”. Key to the scheme is supporting them to access peer-to-peer support.

Leaders can identify “high-quality” help through regional RISE conferences, roundtables and networks, the DfE said. They will also be able to access toolkits and strategies from the RISE teams.

“[It] builds on professional generosity widely seen across the system and we want all responsible for governance and leading schools to know about all the support that is available,” Coulson said.

“It is for each school to choose what is helpful, and we are grateful for all who are contributing to the growing networks of support.”

… but it is optional

Low-attaining schools are not required to take part in universal RISE. In addition, it will be difficult for the government to monitor exactly how many engage with the scheme.

Carter believes it is “hardly a national school improvement strategy” if the DfE has to “ask schools politely to consider using it”.

“A universal offer is exactly that – an offer that does not address the exact needs of the school. The ability to diagnose and then move quickly to support is why trust leadership is a better approach.”

Loic Menzies, an associate fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research, described the service as “inevitably light touch”, noting: “The real job of school improvement is hard, long-term work requiring sustained engagement.”

Letters for high attainers too

On the same day Coulson sent out his missives, education secretary Bridget Phillipson wrote to the headteachers of the 3,326 schools in the top 25 per cent nationally, based on outcomes for poorer pupils.

Congratulating them on their “significant achievement”, Phillipson urged them to help share their experience and best practice with other schools by “engaging actively” with local RISE networks and contributing to roundtables.

United Learning received 36 letters, while Kemnal was sent 11.

Association of School and College Leaders general secretary Pepe Di’Iasio said his union was “not convinced this was the most effective approach”.

He argued that leaders are “already acutely aware of their performance data and are working exceptionally hard to improve outcomes, often under challenging circumstances”. So “an additional reminder of this may have been unwelcome”.

He added: “We would encourage the DfE to explore more positive and supportive ways of promoting the universal RISE offer in the future which reaches every school that may benefit from this support.”

Your thoughts