Dozens of councils do not hold data on how many home-educated children are subject to child protection enquiries – after a damning review into the death of 10-year-old Sara Sharif warned of a lack of information sharing between services

Our findings suggest many councils are underprepared for tough new duties to protect the most vulnerable children.

“These findings are alarming, but not surprising,” said children’s commissioner Dame Rachel de Souza, who said the review had “showed that all the information needed to save [Sara] was available but never shared across services”.

Ten-year-old Sara was murdered by her father Urfan Sharif and stepmother Beinash Batool in 2023 after two years of abuse.

A safeguarding review published last week found information about Sara “would have been available to practitioners”. But it was “not always easily accessible, as Sara’s family life was complicated and information sat within different agencies and systems”.

‘We can’t afford to overlook this’

Local authorities will soon have to sign off on home education for children subject to a child protection plan or enquiry.

Of 70 councils that responded to Schools Week’s freedom of information request, all were able to provide the number of home-educated children with a child protection plan in place.

But just 33 could provide data on children in home education who were subject to a protection enquiry – which is where there is an investigation into a child’s welfare.

Another 33 stated that the data was not collected or held. That included Surrey, which was Sara’s local authority.

However, after being contacted for comment, the council said it did have the data and provided it.

Other councils which could not provide the information included big shire counties such as Nottinghamshire and Lancashire, as well as smaller areas like the Isle of Wight.

De Souza said it was “unacceptable that around half of councils do not hold data on the number of home-educated children subject to child protection enquiries”.

She added: “Schools and services need to understand children’s lives and needs.”

‘We need eyes on vulnerable learners’

“When children like Sara’s lives are at stake, this just isn’t something we can afford to overlook,” said Kiran Gill, founder and CEO of inclusion charity The Difference.

“We need eyes on our most vulnerable learners, and we need to link the data sets on elective home education and suspension with pupils’ vulnerability.”

When approached by Schools Week, the Isle of Wight said it was “reviewing our systems and working with internal safeguarding teams to strengthen information-sharing protocols and adapt our EHE [elective home education] register accordingly”.

It has also been “liaising with the DfE to highlight these issues and explore practical solutions for data collection and information sharing”.

But the other councils did not respond.

The councils that provided the data had 219 children in home education with child protection plans as of October.

In the areas with data on children subject to protection enquiries, there were 158.

Councils underprepared for new powers

Under the government’s schools and wellbeing bill, councils will have to sign off on home education for the most vulnerable pupils. They will also need to assess the suitability of the home learning environment and provide more support to families.

A spokesperson for the Local Government Association said the findings “highlight why councils need to be able to maintain children not in school registers, and it is good the government has legislated for this long-standing LGA ask”.

Schools Week reported earlier this year that some “hollowed-out” local authorities had no dedicated home education officers.

Research by the NSPCC found EHE officers in local authorities “are responsible for an average of 388 children each”.

Wendy Charles-Warner, who runs the home education support organisation Education Otherwise, warned that councils “feel under resourced and funded to deal with their current workload, let alone the projected increased workload from rising numbers and the requirements of the [bill].

“Some officers are pressured to such a degree that I fear it could lead to loss of good officers who understand and care about home educating families.”

Our FOI data also shows that the number of children in home education overall continues to rise.

Home education numbers keep rising

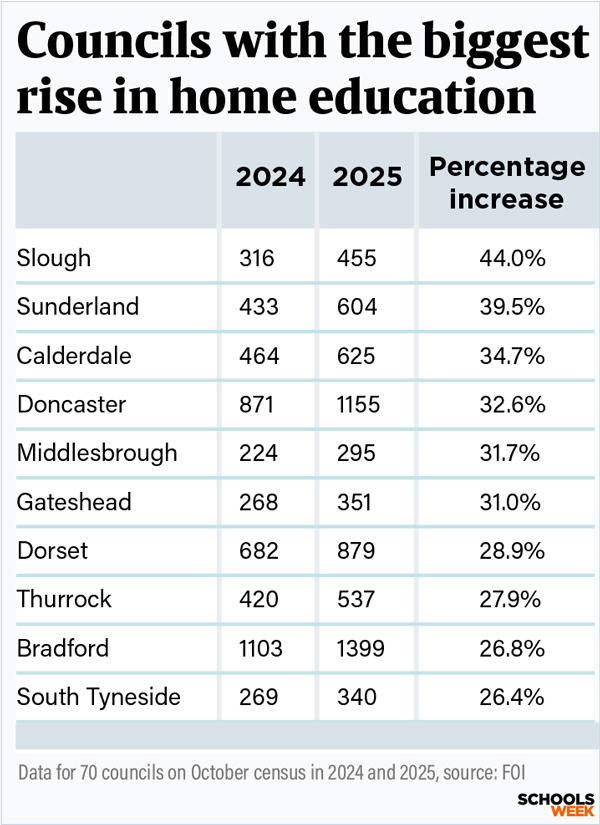

In the 70 council areas which provided data, the number home educated on October census day this year was 13 per cent higher than in 2024. Extrapolated nationwide, that would mean more than 130,000 children.

But some councils saw much larger rises. In Slough, the number in home education rose by 44 per cent. In Sunderland, the rise was 39 per cent.

Middlesbrough saw a 31.7 per cent rise in home education between 2024 and 2025.

Luke Henman, the council’s executive member for children’s services, said it had “robust processes in place to support schools, parents and children if EHE is pursued by parents”.

Dorset reported a 28.9 per cent increase. It said reasons for the rise “include many different factors, including a desire for more tailored support for children with additional needs, concerns about attendance pressures, and experiences during the pandemic”.

The council has a “belonging strategy,” which “aims to strengthen inclusion and engagement in education”.

Thurrock council, which saw a 27.9 per cent increase, said it was “monitoring this issue and working with local education trusts to ensure that all children in Thurrock have access to a good education”.

‘Registers and duties are necessary’ – DfE

Liz McHugh, lead member for children at South Tyneside Council, which saw a 26.4 per cent increase, said she “welcomed government’s plans to give councils more powers and greater oversight”.

A Department for Education spokesperson said there was “currently no duty on parents to notify local authorities that they are home educating, which means that some children could slip under the radar.

“That is why mandatory children not in school registers in every local authority, and accompanying duties on parents and out-of-school education providers to give information for these registers, are necessary.”

The new register would include whether a children is, or has been, subject to a child protection enquiry or plan.

More children kept at home over mental health concerns

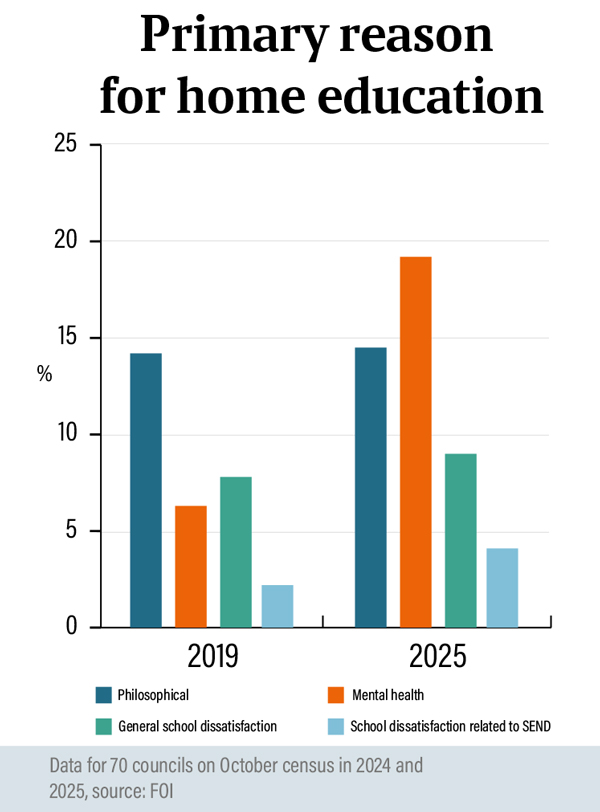

Mental health and concerns over SEND provision are increasingly being cited by families as the primary reason for home educating their children, an investigation has found.

Twenty-six councils provided multi-year data on the primary reason given by families for home educating their pupils.

Mental health problems were cited as the primary reason in 19.2 per cent of cases in 2025, up from just 6.3 in 2019.

General dissatisfaction with school has increased slightly. In 2019 it was cited as the primary reason in 7.8 per cent of cases. It now represents 9 per cent.

Meanwhile, the proportion citing dissatisfaction with SEND provision has almost doubled, from 2.2 to 4.1 per cent.

Liz McHugh from South Tyneside Council said around a third of cases saw parents “reporting the reason for deregistering their child from school is due to mental health needs, which is a growing area of concern”.

Rising SEND among home educated

The proportion of children in home education with an EHCP across all the responding councils has risen from 5.66 per cent in 2019, to 6.44 per cent in 2025.

The proportion receiving SEN support has gone up from 10.8 per cent to 16 per cent.

In Derby, 9.8 per cent of home-educated pupils has an EHCP.

Paul Hezelgrave, the council’s cabinet member for children, said that “unless there are concerns around safeguarding, local authorities have limited powers to challenge parents’ decisions, however we do offer lots of support to home educated families.

“For families who wish to put their young people back into education, we offer pathways for this which include an emotional based school non-attendance pathway, supported placements at both their previous and a different mainstream school, and placements for year 11 learners at a specialist provision or college.”

In Norfolk, 11.7 per cent of home-educated pupils have EHCPs.

Cabinet member Penny Carpenter said they were “currently looking closely at the ages at which children with SEND are leaving school and the reasons why, so we can identify what more we can do to help.

“We have already set up a SEND and inclusion support line which parents can use to find out more before choosing to home educate.”

Your thoughts