Poor pupils in rural schools are more likely to get low GCSE scores than their disadvantaged peers in every other type of area.

Research by the thinktank LKMco suggests that the correlation between the background and attainment of pupils is strongest in rural areas, leaving schools struggling to break the link between deprivation and achievement.

However, schools in cities such as Bradford and Derby aren’t far behind.

In a blog published today Loic Menzies, the chief executive at LKMco, said rural schools were “having particular difficulty breaking the link between poverty and low pupil attainment”.

As a result, it was important for the government and researchers to take “a nuanced view of poverty”, factoring in cultural and ethnic make-up.

“Specific studies of the factors affecting rural schools that serve disadvantaged pupils would therefore be helpful, potentially guiding school and community-level responses.”

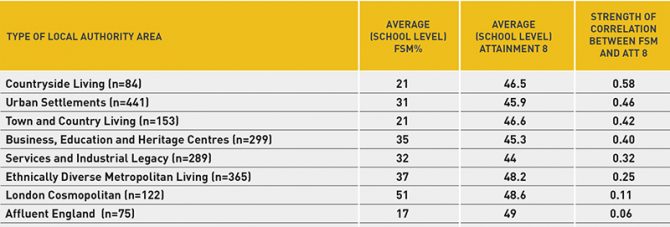

In local authorities defined by the government as “countryside living”, the correlation between the proportion of pupils on free school meals and their attainment 8 scores was 0.58 – the highest of all types of local authority area.

By contrast, the correlation score for those classified as “affluent England”, such as Berkshire and Cambridgeshire, was just 0.06. In London cosmopolitan areas it was 0.11.

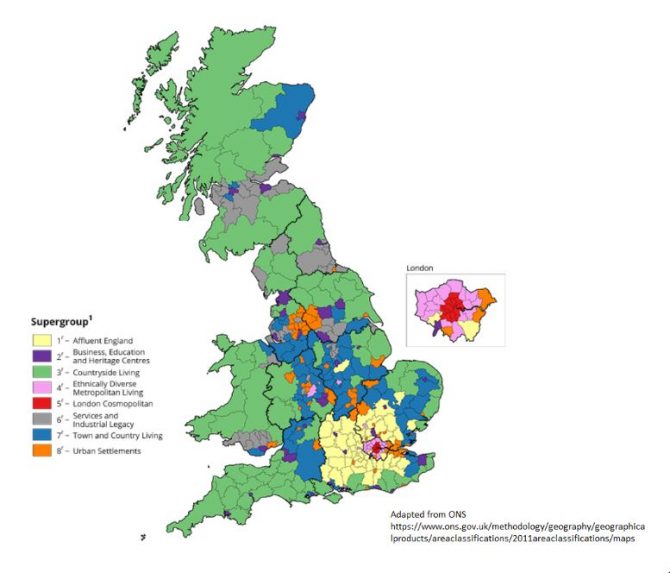

The Office for National Statistics classifies all 388 local authorities in England, Wales and Northern Ireland into eight types, from “ethnically diverse metropolitan living” areas, such as Lewisham in south London and Birmingham, to “services and industrial legacy” areas, such as Carlisle and Blackpool.

Researchers combined these classifications with free school meal and attainment 8 data to find out which areas had the strongest link between deprivation and GCSE outcomes.

Paul Luxmoore, the executive head of the Coastal Academies Trust, with schools in rural Thanet, Kent, said supporting failing schools in such areas should be a top priority for ministers.

“The lack of understanding about deprivation is at the heart of where education policy is going wrong.

“The DfE just looks at the deprivation level and compares a school in Westminster with our schools, and says we’re rubbish. But that deprivation figure has got absolutely nothing to do with the aspiration measure, which simply cannot be measured.”

Unlike schools in areas with high-aspiration immigrant families, such as London, his teachers often had to deal with an “anti-culture culture” from pupils and parents.

The lack of understanding about deprivation is at the heart of where education policy is going wrong

By refusing to provide more resources to struggling schools, the DfE was “shooting itself in both feet”.

The research also revealed that schools in “urban settlement” areas, such as Bradford and Watford, had the second strongest correlation (0.46) between deprivation and attainment.

Emma Hickling, the executive headteacher at the KULB federation of three local authority primary schools in Kent, said rural schools suffered from low pupil numbers.

Many were also Church of England schools, which could be trickier to incorporate into mixed academy trusts because of the requirement to protect their Christian ethos. This limited the cost-saving opportunities of becoming an academy trust.

A DfE spokesperson said the new national funding formula has allocated additional funding of £25 million specifically for small and remote schools.

Research also suggested some challenges faced by rural schools “can be mitigated if those schools make the positive decision of joining a multi-academy trust”, they added.

My colleague, John Mountford and I have investigated the widely quoted ‘attainment gap’ and found it to an illusion. The attainment of pupils in all schools is most strongly predicted by their Cognitive Ability Test (CAT) scores. This relationship prevails in all types of schools in all parts of the country, urban and rural and for FSM and non-FSM pupils alike. The obsession with ‘the gap’ results in pressure on low attaining schools to improve their SATs and GCSE scores by adopting exam results focused teaching methods that fail to develop cognitive ability and which therefore fail to improve the attainment of those pupils from communities characterised by low mean CATs scores (eg rural communities). Like ‘blood letting’ the exam ‘cramming’ remedy makes the patient worse. I have written about this at length in evidence-rich articles. A start can be made here.

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2018/06/02/it-is-the-attainment-gap-fallacy-that-is-damaging-the-life-chances-of-fsm-children-in-the-north-of-england-and-elsewhere/

Where CATs scores are available two patterns emerge.

1. There is no attainment gap.

2. Poor communities and their schools trend to have lower mean CATs scores.

The best educational response is therefore to raise the quality reaching and learning for those pupils in those schools, not pressuring them to increase their exam results through teaching methods that alienate them and produce only short term illusory gains.