Dozens of council-run schools have deficits of over £1 million, shock figures reveal, with some even charged six-figure sums in “interest” by councils for racking up the losses.

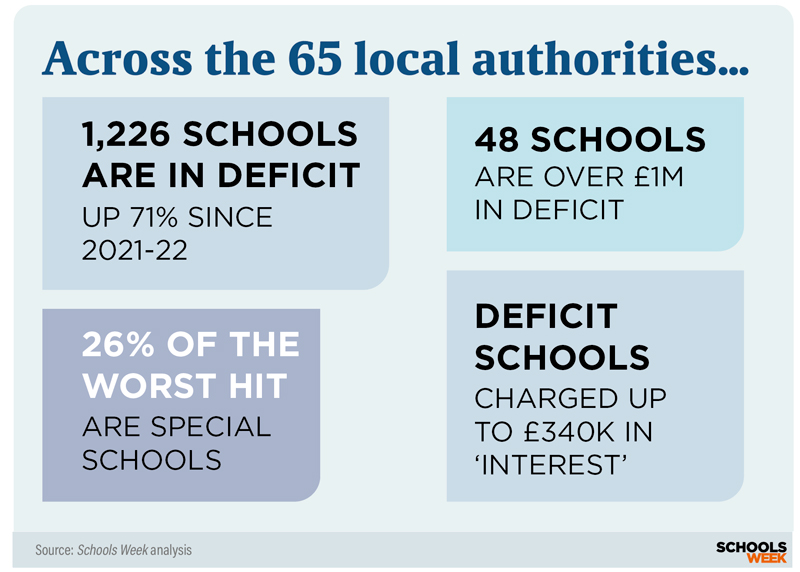

The number of maintained schools in the red across 65 local authorities has leapt by over 70 per cent in just three years, a Schools Week investigation has found, with specialist settings among the worst hit.

Projections for one ailing secondary show its £5.6 million deficit is expected to swell to £7 million in a year’s time. The findings shed more light on the hidden world of council school finances.

Reacting to the findings, Julia Harnden, of the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “It’s deeply worrying. This is symptomatic of an education system that is hugely underfunded, with schools continually being asked to find further savings.”

More in the red

Schools Week analysis shows the number of maintained schools in deficit across 65 local authorities has leapt by 71 per cent, from just under 720 in 2021-22 to over 1,200 last year. This is despite more and more maintained schools becoming academies..

Our investigation identified 48 local authority schools with deficits of over £1 million.

East Sussex reported an increase from one to seven schools in deficit, while Norfolk had a sixfold rise.

The current trajectory of increasing deficits is not sustainable for our schools

A Local Government Association (LGA) spokesperson said the increases were due in large part to falling rolls and “funding allocated on a per-pupil basis”.

Primary pupil numbers nationally have been falling since 2018-19 as a population bulge caused by the 2000s baby boom has moved into secondary.

Eighty-eight per cent of maintained schools are primaries, compared to 69 per cent of academies.

School with £7m deficit

The school furthest in the red was Monkseaton High School in Whitley Bay (£5.6 million). North Tyneside council papers show that it is expected to rack up more losses this year, falling into a deficit of £7 million by 2027.

It has not set a balanced budget since 2016. The secondary’s situation has deteriorated due to, among other things, falling rolls, “higher than average building and maintenance costs” and admission number increases at a neighbouring high school.

The council said this was despite “significant work” undertaken “over a sustained period of time” to address the issues, including staffing reductions and leadership teams cuts.

Deon Krishnan, its headteacher, noted that “historic factors, some going back more than a decade mean the deficit remained difficult to recover”.

Monkseaton was also “one of the first to accept” the DfE’s offer for one of its cost-cutters to “produce a comprehensive review of their finances”, according to the council.

But despite visiting three times, none were able to identify “any areas of further significant savings beyond those already made”.

The local authority will close the school next year, having decided it “is not a position that the council can support”.

Special schools rocked

Another North Tyneside school, Norham High in North Shields, ended 2024-25 with a deficit of just under £4 million.

A council spokesperson said the “challenge” headteachers in the area are facing is “driven by a combination of rising costs, declining pupil numbers, increases in complex needs and changes to national government funding formulas”, adding: “The current trajectory of increasing deficits is not sustainable for our schools or the communities they serve.”

Analysis of each of the councils’ highest-deficit schools shows 38 per cent of them (25) were primaries.

Thirty-one per cent (20) were secondaries, 26 per cent (17) were special schools. Overall, just 5 per cent of council-run schools are special schools.

Finance expert Micon Metcalfe warned that special schools were “more vulnerable” as their funding “has not kept pace” with costs and they tend to spend “much more” on employees due to their “high staff ratios”.

‘Difficult decisions’

There are 48 local authority schools with deficits of over £1 million. Six of them were in Hackney. Anntoinette Bramble, the authority’s deputy mayor, said the challenges faced in the area are “significant”.

Fewer children are being “being born and living in Hackney”, while a “higher proportion of have greater needs than ever before”.

Bramble added the council had made the “difficult decision to permanently close eight” primaries in the past two years.

Harnden added “all kinds” of schools “are being impacted by the paucity of funding”, with the issues “not restricted to the maintained sector”.

But many of the individual school deficits we uncovered eclipse those seen in some of the most troubled academy chains.

A Schools Week investigation in October found that 75 trusts – running 264 schools – had raised concerns about their ability to continue operating as far back as in 2023-24.

Trust ‘benefits’

The St Ralph Sherwin Catholic Multi Academy Trust – which oversees 25 schools across Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Derby – posted the largest deficit (£5.9 million).

It was followed by the Arthur Terry Learning Partnership (£3.9 million) and the Sherborne Area Schools’ Trust (£1.9 million). They ran 23 and 18 schools respectively at the time.

National Governance Association deputy chief executive Sam Henson noted that maintained schools “are also less likely to gain from the financial benefits associated with being part of a group of schools, which academies will necessarily have in a multi-academy trust”.

North Tyneside also acknowledged its “ability to provide direct financial support is limited, and unlike academy trusts, we do not have mechanisms to redistribute staffing or running costs across multiple schools”.

Schools Week previously revealed that government officials are also working on white paper proposals to encourage all schools to join a group.

Stephen Morales, chief executive of the Institute of School Business Leadership, has been in “exploratory conversations” with six councils over how “they can organise themselves into groups”. He said this was a “symptom of a lack of investment”.

£2m interest bill

Some schools are also paying interest to councils on their deficits.

Checks of documents published by 51 local authorities suggest 28 of them (55 per cent) have given themselves the right to charge interest. But only seven are actually doing so.

They received £2.3 million between 2022-23 and 2024-25. Up to 138 schools were charged interest each year.

The Oak Wood School in Hillingdon was charged more than £340,000 over the period. It has a deficit of £2.3 million. Dan Cowling, the secondary’s headteacher, said the payments make it “almost impossible to balance the budget now”.

Despite schools’ best efforts, this inevitably harms children’s education

He’s also unable to “put money away for a rainy day” adding: “The building is starting to look a bit shabby, and we can’t commit to any big spends on things.”

Cowling also believes it’s “unfair” maintained schools can’t receive government bailouts in the way academies do. Instead, they have to go to their local authority for financial assistance.

The council said charging interest on cash advances to schools in deficit “was an approach that was carefully considered and discussed with the Schools Forum and was agreed as a fair way of maintaining the support provided, without disadvantaging schools in surplus, or the local authority”.

Education ‘harmed’

In response to a survey conducted by the National Association of Headteachers earlier this year, 98 per cent of leaders said their school “did not have sufficient funding to fully meet the needs of its pupils”.

Paul Whiteman, the union’s general secretary, stressed the “only way” for some to balance the books “is by cutting staffing, resources or provision”.

He added: “Despite schools’ best efforts, this inevitably harms children’s education.”

The Department for Education was approached for comment.

Finally, Schoolsweek is beginning to balance the number of critical MAT articles regarding finances. This issue goes straight to the heart of the transparency debate. MATs are far more regulated, audited (and pilloried), than LA maintained schools. Academies are not allowed to run deficits and if they do, this is published and an improvement notice issued. Further, MAT leaders must publish their salaries on the school gate, an LA school leader does not, even though the LA system allows the head of a single large school in London to earn £191,862.50 (L43 + 25% uplift for r and r). Whilst ranting, LA schools pay nothing for audit, MATs must pay tens and tens of thousands for annual external, and external internal, audits. Money which would be far better spent on educating children.