Jess Staufenberg meets a middle leader intent on breaking the glass ceiling, if only for others

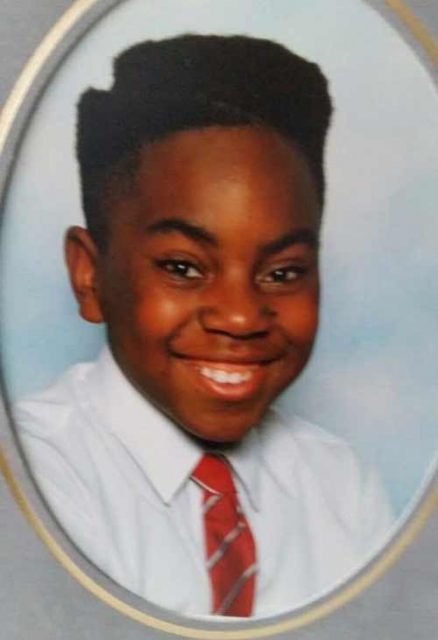

It’s rare for Schools Week to feature a middle leader (our main readership base is senior leaders), but T’Challa Greaves, lead practitioner for science at Meridian High School in Croydon, is a powerful voice to listen to. In January we heard him deliver a thought-leadership talk at the Diverse Educators conference, weaving together personal narrative and structural analysis.

He has a YouTube channel called Science and Muscle, which aside from fitness tips and lab lessons, sees Greaves deliver talk pieces to camera on subjects including ‘The effect that racism has on mental health’, ‘Toxic masculinity’ and ‘Is there racism in teaching and education?’. He talks not just about one issue, but a combination of intersecting issues that face teachers and pupils across the system; mental health, racism, gender, vulnerability and ambition.

It’s a good job he’s speaking out, given the significant lack of high-profile school leaders from black, Asian or ethnic minority (BAME) backgrounds. Our summer investigation revealed that 98 per cent of the largest academy trusts were run by white bosses, a higher proportion than two years earlier. It’s discouraging to say the least, even more so as Black Lives Matter marches protest problems of representation and brutality around the globe.

Greaves is someone staring up the ladder at top academy roles, wondering whether he’ll be given a chance.

One thing he says really hits home. “Every school I’ve worked for in 18 years, there’s been no one BAME on SLT.”

It’s clear talking to Greaves that he has a great passion for his subject, his sector and chosen profession, but a real sense of sadness that for all his efforts, there seems to be an invisible ceiling he’s seen other staff, largely from a white background, pass through more easily. He left a teaching job at a school in his hometown of Birmingham after a decade because “deep down” he felt unsupported by senior staff to aim high.

“It was seeing the same faces on SLT. It was seeing people I had trained up in my department go on to be assistant headteachers elsewhere in five or six years.” The relative lack of vertical movement is not for shirking responsibility: at his current school he is the oracy lead, NQT mentor, works on the beginner teachers’ programme and is a form tutor lead. “People from BAME backgrounds need to stop being given pastoral leadership roles and be promoted properly.”

That feeling of looking upwards and seeing no one with a face like his started young. Greaves’ mum is from Jamaica and dad from Barbados, and in 1980s Birmingham he had peers from a similar background around him but no staff. “The big struggle for me at school was not seeing a lot of teachers who looked like me. Partly because of that, at secondary school I was trying to fit in with the kids who rebelled.”

People I had trained up went on to be assistant headteachers in five or six years

The importance of having two parents who hugely valued education is clear in what happened next. “It got up to year 9 and my mum showed me my year 7 results compared with what I was getting now. That was kind of eye-opening. She’d also kept a piece of paper I’d written when I was 11, saying ‘I want to be the first in my family to go to uni’ and she showed me that. That made me realise that maybe, deep inside me, there was a drive in me to go and achieve more.” It’s a powerful moment of parental guidance.

Teachers both helped and hindered him on his way. Greaves attributes his failure to pass GCSE maths the first time to his unthinking teacher keeping a pet tarantula on the front desk (sending a young Greaves straight to the back row). Another, his English teacher, Mrs Deane, he talks about with deep affection. “More than anyone, she was the only person who really understood me. I think mostly because of her I got through English.”

But when he followed his role model into teaching, Greaves soon found himself unsupported in a profession that requires you to emotionally support others on a daily basis. In one of his first jobs, he recalls “year 11s spraying their arms with aerosol at the back of the class and lighting them” and feeling overwhelmed by how many pupils he wanted to help. “When I first started teaching I genuinely panicked about ‘how am I going to get these children to understand that even though they’re not in the right circumstances, there’s a much bigger picture out there for them’.”

The sense of responsibility made him impatient for change. “I was a defensive and angry person at this point. If I thought something should change, I would go straight into the headteacher and say, look, this isn’t right, why isn’t this happening? Now I know it’s about going through the right channels.” Determined to make a difference, Greaves went for six jobs in four years, succeeding in two but never receiving feedback on how he could improve. In one of his YouTube videos, he talks about how his African name, T’Challa, may have had an impact on job responses. Without mentoring, the constant drive to try to make a change and advocate for his students was slowly draining him.

Aged 32, Greaves stood back and took stock. He signed off work with depression and saw a counsellor. For the first time he discussed his feelings and events in childhood, including that when he was 10 his mum had a stillborn child – a traumatic ordeal for the family. “It’s so important to seek help and get things off your chest. I was a big jovial character, that alpha man in the changing room. For 15 years, I’d never said no, I was one of those people who always said yes to everyone. It was about learning I could take time out.”

People from BAME backgrounds need to stop being given pastoral leadership roles and be promoted properly

He pauses and unfolds his arms. “Most men don’t like to fail. I see it in the boys I teach now, they don’t want to fail or seem weak so they won’t speak up. I want to help young men realise that regardless of what childhood experiences they’ve had, it’s not the end. Speaking up about feelings and emotions helps.” Greaves decided to leave his home city and move to London. Perhaps even more bravely, he chose not to leave teaching. Instead, he landed a job tutoring young footballers at Chelsea F.C. Academy – where better to help young men feel they don’t have to project a particular persona?

In a perfect segue, it is at this point that Greaves mentions his pet rabbit. “Me and Wolverine…,” he begins. Who, sorry? I say. “My rabbit. Wolverine. I’ve got two more now. Thor and Jubilee.” Fans of X-men will recognise a theme. Naming fluffy animals after heroes with superhuman powers is a lesson for all of us in not judging by appearances. Greaves also shares his first name with a superhero, the legendary king T’Challa of Wakanda, in Marvel’s Black Panther.

What Greaves really nails is the importance of bringing people in – of ensuring everyone feels deeply accepted and invested in. It’s not enough to assume it’s happening. I ask what he’d do as a headteacher.

I believe in myself. But it’s about growing that faith and belief in other people

“A massive part of any school is the community. I want the community of the school to feel they belong to the school. I’ve been to parents’ evenings where teachers aren’t talking about the community or what the school is doing, just the individual child. We should be talking more about ‘this is where we’re going, this is what we’re doing with your child. Come to this play, this event, this club’. The strengths of the school are always there, but I don’t think parents always see the strengths. The more you engage the parent, the more students are engaged.” It’s a perspective that sounds quite obviously beneficial to any SLT.

But when I ask Greaves whether he’ll be a head, he hesitates for the first time.

“Even with 20 years left of my career, I’m still not sure. There are so many factors involved – being in the right place at the right time. I’d love to. I have the belief in myself. But it’s about growing that faith and belief in other people. I just can’t say.”

Your thoughts