James Tooley’s vision of no-frills private schools is now a reality in England. How afraid should the state sector be? John Dickens finds out

“If I were a highly qualified teacher working in a publicly funded school… I would be afraid of him. Very afraid.”

So concluded a 2013 interview with Professor James Tooley. That was in the liberal-leaning Guardian newspaper, which matters, given what Tooley spends his time doing.

Seven years later, what Tooley described back then as “just an idea in my mind” is a reality. The Independent Grammar School: Durham (IGSD), billed as the country’s first low-cost, or “no frills”, private school, opened in 2018, charging parents £52 a week, or £2,700 a year.

We’re getting a sense there’s definitely a market for this

Schools Week has had several requests to visit the IGSD turned down, probably due to the school opening with just six pupils. So we gladly took up the chance to interview its chair of school board at the University of Buckingham – where he has recently been appointed pro-vice chancellor after 21 years at Newcastle University – to try to find out just how afraid the state sector should be.

Tooley is down-to-earth and relaxed as we chat about our surroundings. He calls the country’s oldest independent university his “spiritual home”. He is smartly dressed in a suit, with a sort of psychedelic tie-dye pocket square suggestive of an underlying eccentricity.

But he also chooses his words carefully, pausing to think before answering questions – particularly about why he believes there is a case for low-cost private schools in England.

He says some parents are “very dissatisfied” with state schools – either because their child has special needs (“whether that’s because they are gifted or have other special needs that are not being catered for well”) or because the school is “not accountable to them”.

But opening with just six pupils doesn’t really seem to evidence that claim.

Tooley puts the numbers down to IGSD’s opening being twice delayed. “The regulation of private schools was much more onerous than I thought,” he says. “Antagonistic” unions also picketed open days.

He says the school now has 25 pupils and is rated ‘good’ by Ofsted. It’s still way off the 65-pupil capacity of its converted church setting, but Tooley believes they will hit the 40-odd pupil mark next year, allowing them to “break even” financially.

IGSD quietly upped its annual charge last year to £58 a week, £2,995 annually. However, it’s still way below the sector average of £4,763 per term for private day schools.

Some quick maths. Assuming break-even at 45 pupils, at £3,000 each, that’s £135,000 a year. Doesn’t seem much to pay four staff (two teachers and two assistant teachers) as well as rent and so on. Full capacity would mean around £60,000 profit.

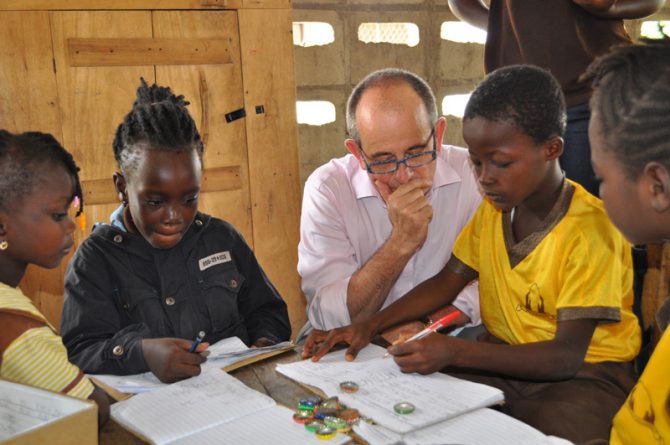

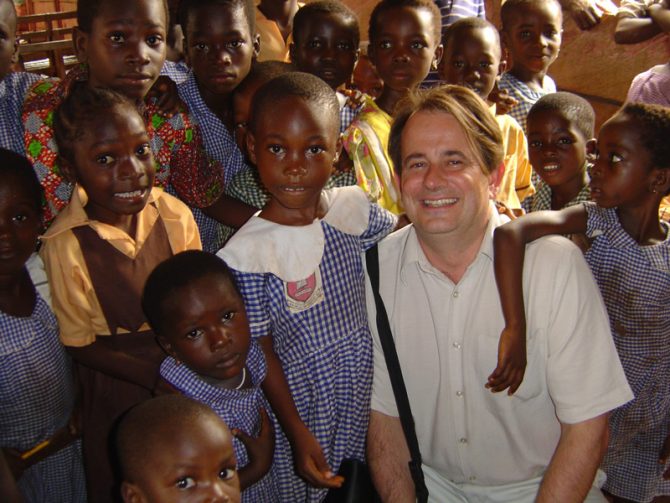

Tooley has opened low-cost private schools in developing countries across the world. One of the concerns is that they are run largely by unqualified teachers on low wages.

He says he can’t reveal his teachers’ salaries for data protection reasons, but I press again. Are they on the newly qualified teacher scale?

“Yes, absolutely, the teachers are not paid less than if they were in the state sector.”

The numbers still don’t quite seem right.

Undeterred, Tooley is now looking for seven sites across the north-east to expand his “no-frills” chain “over the next few years”.

“We’re getting a sense there’s definitely a market for this. You would say it’s a tiny market so far –I’m very happy with that observation – but I think we’re going to grow.”

The model now seems to make more sense: that £60,000 profit across seven schools is now £420,000 (and that’s before any economies of scale).

He says “obvious” locations include Sunderland, Gateshead, Middlesbrough, North Shields and Newcastle.

Why the north-east? Tooley says it’s partly because that’s where he was based at the time, along with his funders who are “at this stage entrepreneurs, friends and family”. But it’s also a “good area to be working because it’s known to be an area with educational needs”.

He also says around 30 people have got in touch – across England and also in Dublin, Scotland and Wales – to ask for advice on replicating the model. One of these – a “no frills” school charging parents £100 a week mooted for London – seems to have gone off the radar after we first revealed the plans in 2018.

Providing advice for competitor schools intrigues me. Is Tooley not in this for the money then? Does he not want the “James Tooley Chain” to run them all?

I’ve not come into it as this person who wants his model all over the place

“I have no ego. When I was younger, probably yeah, it would have been something like that.

“I’ve not come into it as this person who wants his model all over the place. I want to see this work from a philosophical point of view. I’m very happy there are competitors, but also replicators.”

But let’s say the model does take off – is he happy for them to make state schools unviable?

“If they [state schools] are not doing a good job and parents think we can do better – absolutely I’m happy with that.”

I ask about an opinion piece he wrote for the Telegraph, titled ‘Only a new breed of low-cost private schools for the masses can save the UK’s failing education system’.

So why is the state system failing?

“I didn’t like that title – I never talk about failing. My belief is we don’t want the state in education. The article was trying to say that I believe these [low-cost private schools] will be better than the state system.”

But if there’s a need for an alternative – surely the state has to be getting something wrong?

“I’d rather come from it at the other angle,” Tooley adds. “Why do we want the state involved in education? The state is not involved in most other areas of our lives – it doesn’t feed and clothe us, it doesn’t provide shelter. Why is education different?”

I point out that the argument for state education seems pretty compelling – it means everyone is entitled to an education, regardless of where you’re born or the amount of money you have.

But Tooley cites the Newcastle Commission report, published in 1861 (nine years before the 1870 Education Act that established compulsory education), which, he states, actually found 95.5 per cent of children were already in school for six years.

As well as public and church schools, a “large proportion” of that provision was “for-profit schools” – which he says were the low-cost private schools of the day.

“A small number of kids were not in school, so we wanted the state to come in and provide opportunities for all. But then the state took over.

“But why do we want the state to be involved? It’s clearly in other parts of the world not working. It also breaks the link – as parents, the education of our children is no longer accountable to us.

“We have to give our children to the state system and they educate them in the ways they want to. That seems wrong to me and undesirable. A much better system for me is where parents are in charge and the schools are accountable.”

My belief is we don’t want the state in education

So, let’s say Tooley’s model does take over. That five per cent of pupils will still be there – what happens to them?

He says there are “ways around this”, such as tax credits or targeted vouchers, which he explains could work in a similar way to our current system for welfare payments: “Just because some parents don’t feed and clothe their kids, we don’t then say universally we have to have the state feeding or clothing all kids – let’s target assistance where it’s needed.”

Tooley didn’t always believe this. One of five children, he attended a comprehensive school in Bristol before studying at Sussex University and getting his first teaching job in newly independent Zimbabwe in 1983.

“As a socialist at the time, I saw an advert in the Guardian – it got into me this whole excitement about Africa and development.”

His views changed when he started work on a PhD to challenge then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s 1988 education reform act to “introduce elements of markets into education”.

As part of his research, he read E.G. West’s Education and the State. It made him realise “instead of us taking state education as the status quo, private education should be baseline… That’s when I became converted from being a socialist to a classical libertarian.”

So should highly qualified teachers be afraid of him? What happens to them if an army of low-paid, less experienced staff do take over?

“They can open schools. If you’re a highly qualified teacher and devoted and committed and passionate, then there’s so many more opportunities open for you than just staying in the state sector.”

Tooley seems non-plussed when I say the free school programme already offers this. His model, he explains, is “predicated on parents wanting control and schools that are accountable to them”.

“If they don’t like what we’re offering, then they won’t come. If this is something that is of interest to parents, then great.”

It doesn’t sound like teachers should be too afraid, then. Not just yet, at least.

Your thoughts