Equity and social justice are what drives Challenge Partners CEO, Kate Chhatwal – and yes, you can call her stubborn, writes JL Dutaut

Call it fate or serendipity. Sometimes, the most transformative moments in life can come to you in the form of a chance conversation in a swimming pool in Loughborough.

Though on social media and in education circles she is better known for her obsession with running, that is how Kate Chhatwal became executive director of Southwark Teaching School Alliance. Initially bouncing ideas about with the headteacher she’d just met poolside as to how and who to recruit to the position, she eventually followed her own leadership advice and applied to do it herself.

In that role, she found a happy marriage of the strategic and the operational, getting buy-in from local headteachers, providing them with development opportunities, and using that as the springboard to “reach further down into their schools.” Here too she was able to roll out initiatives that matter to her greatly, such as women’s leadership programmes.

Today, Chhatwal is the CEO of Challenge Partners, a growing network of schools using peer review to achieve school improvement. But for the past five years, complementing this and the numerous other roles she has held with the likes of Ambition Institute, ASCL and the Future Leaders Trust, she has also been the vice chair of the Leading Women’s Alliance, which she co-founded.

Everybody suffers from imposter syndrome to a certain extent

Her pursuit of equity and justice in education, coupled with her seemingly relentless energy – she is also a trustee of both STEP Academy Trust and The Charter Schools Education Trust – saw her rewarded with an OBE in this year’s New Year Honours. “It was one of the rare moments in my life when I was left totally speechless. I was humbled, overwhelmed, and a little bit embarrassed.”

Given her contribution to education, that embarrassment is surprising, but when I ask her about imposter syndrome, she is typically guarded. “Everybody suffers from imposter syndrome to a certain extent,” she answers, “but it’s seen to be more keenly felt amongst women.” If Chhatwal suffers from it, it certainly doesn’t seem to have held her back. She puts her success down to two factors: her stubbornness and her parents.

After 11 years as a Department for Education civil servant, rising from recent PhD graduate to seniority in a job where she “felt supported as a woman to be able to progress”, she moved to the Future Leaders Trust where her responsibilities included supporting participants into headship. “What I found was that, despite equal numbers of men and women accessing the ‘Headship Now’ programme, men were still getting more headships. I dug into it and started to hear stories from female participants about the reasons they were being knocked back.”

She tells me about the applicant in the northeast who was told that “for this mining community we feel that we need a male figurehead”. Another whose feedback was that “we’ve already got an all-female leadership team and quite a lot of oestrogen flying around, so we probably need a man”. Another story includes two final candidates, both Future Leaders alumni. “They rejected the woman saying she was too young for the job, and appointed the man who was a year younger.”

“I got really angry about it on the grounds of basic equality, but more than that. We know we haven’t got enough headteachers, and we’re not drawing from the whole pool because of prejudice.”

I got really angry about it on the grounds of basic equality

Digging further still, Chhatwal found that “there were also things about the women themselves that were holding them back. We recognised that we needed to work to change the system, but we also needed to work with women individually.” That’s what the Leading Women’s Alliance continues to do, and it is so much proof of Chhatwal’s self-proclaimed stubbornness.

As to her parents, both of whom come from the northeast, they taught her and her two younger brothers a simple lesson: “They didn’t expect any more or any less of us than that we did our best and that we tried our hardest. They did better than their parents in socioeconomic terms, and they expected and wanted the same for us.”

Chhatwal went on to blaze a trail through academia and into the civil service. After a degree in politics at Liverpool University, she studied for a PhD in social and political science at the European University Institute, having already zeroed in on education as a focus. “I’d gained a place on the civil service fast stream and when you do that you get to write down which are the departments you would and the ones you wouldn’t work for. I made a very strong case for going into education, which fortunately was accepted.”

That educational focus was the result of a slow percolation, but Chhatwal puts the initial impetus down to her A level experience at Larkmead school in Abingdon. “I had a small-c conservative upbringing, very rural and very traditional. The community was completely white. Not entirely affluent, but fairly homogenous. When I got to my A levels, sociology really opened my eyes. It challenged me to think differently, and to recognise some of my own privilege.”

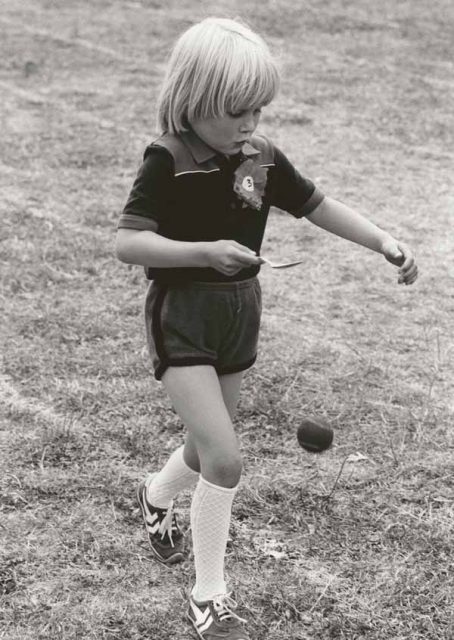

Liverpool university is well known for its politically active students, and Chhatwal was no exception. On the picket line with striking dockers, she stood out somewhat, “a middle-class white young woman in cut-off jeans, striped tights and Doc Martens”. She protested too about student loans and the Criminal Justice Bill, combining campaigning with learning how policy was made. “There was a confluence of political activism and the recognition that education is the way to change not just individual lives but society as a whole.”

“I think the power in education is about building communities and I’m probably more interested in it from that point of view than from the point of view of individuals being socially mobile within a class structure. At my heart, I’d still like to see that class structure diminish significantly in importance in this country.”

I’d like to see class structure diminish significantly in importance in this country

At the DfE she worked closely with David Miliband, and was strongly influenced by his passion for excellence and equity – values she has taken with her to Challenge Partners. Her defining role there was leading the National Challenge under Ed Balls and Jim Knight. But her learning curve was as much about herself as about the world of education. The political idealist took a pragmatic turn.

“I thought that what I wanted to do in joining the civil service was to think great thoughts and write great strategies that would lead to the world changing. Over time, I got into more and more operational roles that really made a difference to schools and I got quite addicted to that.”

There was to be no return to “anodyne policy papers”. “Change happens in classrooms. Having the right policy context is important, but there are many things that the profession can do for itself without permission. Many of the answers to the challenges we face already lie in the system, but they get locked up in individual departments, schools and classrooms.”

And so, after a few years of exploring possibilities, at Challenge Partners Chhatwal has found the place from which to unlock that potential. “Actually opening up your school and being challenged by colleagues is as much of a prompt to action as Ofsted coming in and bashing you over the head with the latest framework. They come not with a big stick but with a hand on the shoulder.”

There are many things the profession can do for itself without permission

The appeal of peer review means Challenge Partners is seeing year-on-year growth of its network, and while growth brings new challenges, the organisation is not content to consolidate under her leadership. They have recently piloted ‘growing the top’ to provide targeted support to systemically excellent schools, “who are often expected to be givers but don’t get a lot of nourishment themselves”. Research is due to be published about what makes them systemically excellent too. Another project aims to develop trust-level peer review; its pilot has been evaluated by the NFER and that too is due to be published soon.

More proof of Chhatwal’s stubbornness? It’s not the word I’d choose to describe a woman going to such great lengths to lead by example.

But it is the one she chose herself.

Your thoughts