The country’s most disadvantaged pupils are twice as likely to attend Oxbridge if they live in a region with grammar schools compared to a non-selective area, a new study has claimed.

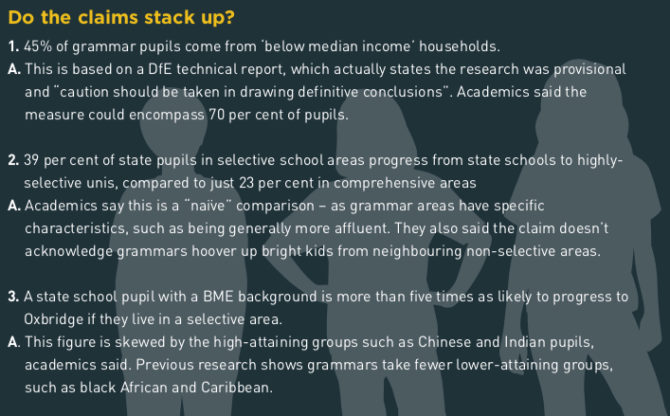

The report, published today by the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), also found 39 cent of pupils in selective school areas progress to highly-selective universities, compared with just 23 per cent in comprehensive areas.

HEPI has today called on the government increase its expansion fund so grammars can open “branch sites” in disadvantaged areas.

It is disingenuous to compare university entry from selective authorities when grammar schools import vast numbers of high attaining pupils from non-selective areas.

But the study is likely to be highly contested in the face of stacks of critical research shooting down claims that grammar schools boost social mobility.

For instance, a study by Durham University’s School of Education in March found grammar schools are no more effective than other schools once factors such as poverty, the language spoken by pupils at home, and special educational needs were taken into account.

The study, based on the key stage 4 scores of pupils in 2015, found the higher average attainment of grammar pupils only came about because they are cherry-picked, and grammars did not drive up overall results in their areas or reduce the poverty gap.

Previous research has also suggested the government’s official progress performance measure actually favours grammar schools.

But Iain Mansfield, a former civil servant and author of the HEPI report, claimed a “narrow focus” on eligibility for free school meals has “ignored many other measures of disadvantage, including ethnicity, parental education and broader income disparities”.

While just a handful of pupils in most grammar schools are eligible for free school meals, the HEPI report found 45 per cent of pupils at grammar schools are from households with “below median income”.

Education Datalab has previously challenged analysis based on below median income, finding that pupils from “ordinary working families” won’t get access to grammar schools.

But Mansfield claimed his report shows that “for many disadvantaged children, selective education makes a vital contribution to social mobility”.

The report found a state school pupil from the most disadvantaged POLAR quintile is more than twice as likely to progress to Oxbridge if they are in a selective area than a non-selective area. (POLAR stands for the participation of local areas, it classifies areas into five different quintiles based on how likely youngsters are to attend university)

Nick Hillman, HEPI’s director, added: “Researchers line up to condemn them for inhibiting social mobility, and the schools do not perform well on every single measure.

“But the full evidence is more nuanced and shows some pupils benefit a great deal.”

HEPI has called on the government to commission detailed research on the impact of selective schools on the social mobility of children from households below the median income.

But Dr. Nuala Burgess, chair of Comprehensive Future (pictured), questioned why the report chose to ignore the “tried and tested” free school meals measure as a proxy for disadvantage, adding “below median income families” would include “many lower middle class, well-educated families, such as teachers, who are hardly disadvantaged in educational terms”.

She added: “It is [also] disingenuous to compare university entry from selective authorities when grammar schools import vast numbers of high attaining pupils from non-selective areas.”

She pointed out that, for instance, Trafford grammar schools import nearly 30% of pupils from outside the authority, while in Southend it’s over 50%. “This is bound to skew university entry figures simply because higher proportions of the highest attaining pupils are being educated in the selective areas,” she said.

A spokesperson for the DfE said selective schools are “some of the highest performing schools in the country and an important part of our diverse education system”.

“That is why we continue to support their expansion, through the selective school expansion fund, where they meet the high bar we have set for working to increase the admission of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds.”

However, an investigation by Schools Week found the targets set by each of the 16 grammars awarded expansion cash will still fall short of the percentage of disadvantaged pupils on their local authority.

The report’s author Iain Mansfield makes it clear in his foreword that the report’s opinions and conclusions are his own. This becomes apparent when he introduces a narrow benchmark of how many progress to highly-selective universities especially Oxbridge.

Mansfield admits comprehensive schools succeed in preparing pupils with potential to enter higher education. This is not a ‘shocking indictment of the comprehensive system’ which he later claims when writing about BME state-educated students at Cambridge. https://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2019/01/comprehensive-schools-help-potential-pupils-enter-university-new-report-shows