As a former national lead for equalities with Her Majesty’s Inspectorate, I am deeply concerned about the inclusion judgment at the heart of Ofsted’s new framework. The evidence suggests they have not learned lessons from their previous foci on other pupil groups and ignored good practice.

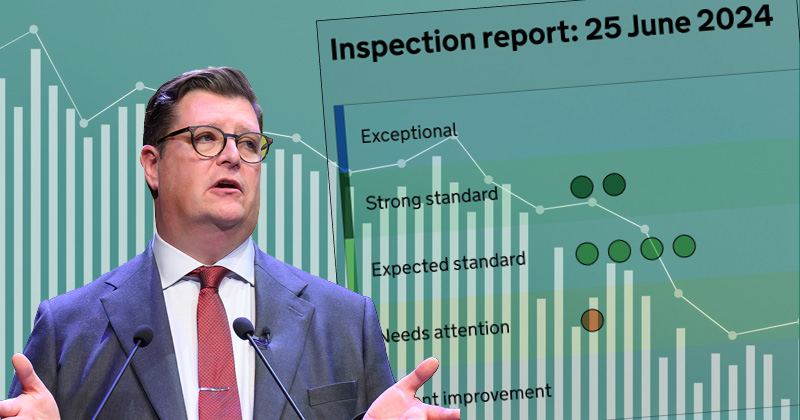

Ofsted’s ‘inclusion’ grade references the 2010 Equality Act, which covers nine protected characteristics, including ethnicity. SEND pupils, children known to social care and those who ‘may face other barriers’ are now at the core of inspections, with the intent of shifting focus from compliance to meeting every student’s needs and enhancing accountability for SEND.

However, the definitions of SEND and ‘barriers’ are vague. Does SEND only include those with identified needs, receiving support or intervention, or with mandated EHCPs? Or will inspectors seek out unidentified needs during observations?

Meanwhile, the Inclusion Task Group’s narrow focus on SEND makes no mention of ‘disadvantaged’, Gypsy, Roma and Traveller, EAL, or white working-class pupils.

Yet analysis of socio-economic and ethnic profiles of SEND students would show most straddling at least one or more of these pupil groups. Hiving off pupils into distinct groups based on labels in this manner is neither inclusive, nor instructive.

SEND pupils are disproportionately more likely to be persistently absent from classrooms, suspended or excluded for poor behaviours. Analysing why should be at the core of inclusive inspection practice.

But bizarrely, in 2019, senior Ofsted leaders prevented inspectors from accessing Analyse School Performance (ASP) as an insightful starting point for discussion with senior school leaders. That injunction remains in place, so inspectors will be implementing this framework (just like its predecessor), blindfolded.

Consistency demands that inspectors and schools have a common understanding of inclusion

Without detailed external attainment, exclusions and suspensions data, and with schools under no obligation to share their internal data, how will they verify the authenticity of School A’s highly convincing narrative about reducing exclusions for SEND students?

And how will School B, too busy being truly inclusive to develop such a narrative, fare by comparison?

My experience is that Ofsted’s commitment to equalities focused on schools meeting their statutory requirements on discrimination.

The detailed audit I undertook in 2008 showed that only 40 per cent of reports mentioned ‘minority ethnic’ pupils. This led to national and regional training for inspectors, with specific guidance on how to inspect race equality, exemplars of good report writing and school case studies of good practice.

Focusing on meaningful language was key. Bland report-writing full of stereotyping and vagueness (e.g.: “All pupils, including those with learning difficulties and disabilities, or from minority ethnic backgrounds make progress at similar rates”) was replaced with contextual specificity (e.g.: “Effective language support and participation in creative subjects helps students at early stages of learning English become part of the school community, accelerating their language skills”).

As a result, inspectors faced challenging (but quite necessary) conversations when sometimes stark, uncomfortable truths in schools were exposed – for instance, where data indicated disproportionate exclusion numbers for Black Caribbean pupils, or where children did not report racist bullying for fear of not being listened to.

They were also able to celebrate previously unseen well evidenced success: leaders shared the positive impact of peer mentors, reductions in bullying and progress in early English acquisition.

The focus on race equality was abandoned in 2012, replaced by ‘pupil premium’ pupils, and now by SEND and children known to social care.

But whatever the focus, consistency demands that inspectors and schools have a common understanding of inclusion, share accurate admissions, progress and exclusions data on the intersectionality of pupil groups and know what good practice looks like.

If not, inspectors will face a tsunami of complaints from schools on the fairness and reliability of this core judgment as schools face a grilling from inspectors on ‘unmet’ SEND needs and ‘barriers’ unearthed during a day and half’s worth of unvalidated lesson observations.

One ambiguous example in the new inspection guidance tells us: “Leaders have considered appropriate adaptations to teaching […]. These are not well matched to pupils’ needs.”

How can both statements be true? And in any case, are all inspectors equipped to judge whether adaptations are effective or well-matched to needs?

Schools scrambling desperately to conform to inspectors’ ‘inclusive’ checklists seriously risks discrediting the integrity of the Ofsted framework and Ofsted’s commitment to equalities, all while losing sight of the government’s reform agenda to ensure all pupils to achieve and thrive.

I agree totally about the intersectionality aspect of inclusion. Putting children and young people into one group that they belong to instead of considering how the different ways in which they can be grouped affect and impact them is too narrow. It ignores the impact of things like ethnic background on SEND – one institution I worked at noticed kids from White backgrounds were more likely to come forward for SEND assessments etc. or seek exam concessions than kids from non-White backgrounds.

Thank you Meena for fanning the flames of the critical debate that is necessary to support all schools to be genuinely inclusive, and thank you Ofsted for making Inclusion a key aspect of the new framework. My comments last week about potential exclusions of pupils that might ‘interfere’ with the highest grade for Achievement in an inspection, is not entirely unrelated. Academic Progress for all pupils should be one goal in all schools and another should be a genuine Inclusive culture, but neither should be driven purely by the pursuit of the highest Ofsted judgements. In the best schools these goals are rooted in values-based leadership that recognises how schools are critical in shaping the future society! Let’s have the debate about detail out in the open now and then get on with building the preferred future for most stakeholders : a more inclusive country.

Reading this article makes you realise the constant obsession with focusing on one group or another. There is an obsession with cumulative data that often means pupils that do not need help are being targeted and those that do need help don’t receive it. A perfect example being a pupil whose parents could apply for FSM but don’t and as a result the pupil is not listed as FSM or PP but has underperformance linked to their deprived background. Sporting trends in cohorts is helpful but surely should not be a metric that is used to compare schools.

Teachers are not allowed to teach to the exam for fear of being judged by Ofsted yet Ofsted are repeatedly relying on entrenched hard to shift national trends in academic outcomes as a means of evaluation.

I am totally committed to supporting best progress for SEND pupils but given that the SEND group will have many pupils with specific learning difficulties this is akin to expecting a group of shorter people to beat their taller counterparts in a reach test it is common knowledge that staff feel professionally safer from judgements about academic outcomes in schools with low needs and low disadvantage. Until we truly as a society and inspectorate acknowledge the full range of outcomes the same story will perpetuate but I can’t help feeling that is what the aim is