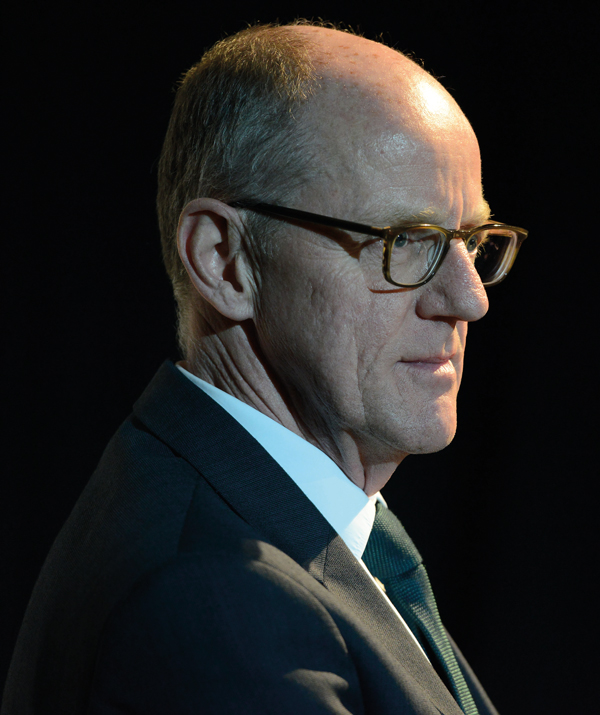

Nick Gibb has three large maps taped to the walls of his Department for Education office.

They show regional figures for pupils’ reading and writing achievements aged 11, the phonics pass rate for six- year-olds, and how many children passed the English Baccalaureate subjects at GCSE. If you didn’t know already that the minister for schools is concerned about children learning to read and develop traditional knowledge, he doesn’t want there to be any doubt.

First brought into the department under Michael Gove, Gibb served for two years as an education minister before being replaced by the Liberal Democrat David Laws. Last year, when Nicky Morgan took over, Gibb shuffled back. But his connection to education is even longer serving. A shadow education minister since 2005, he was a member of the education select committee before that.

His passion stems for an evangelical zeal for reading, in particular the teaching of synthetic phonics, in which children are taught to sound out words.

“It is upsetting when you meet nine-year-olds who can’t read a single word. One example I used in an article recently was of a school I visited just before the 2010 election in north London where a voluntary reading group was trying to help this child who wasn’t nine, she was in year 6, and had flash cards in front of her.

“She was struggling and eventually she was able to read the word ‘even’. I asked the volunteer reader if we could cover the letter ‘e’ and see if she could read the word. She couldn’t read ‘ven’ . . . and yet the reading book she had been asked to read was about dinosaurs.”

He grimaces: “This child struggled to read the word ‘even’, and couldn’t read the word ‘ven’ but was supposed to read ‘tyrannosaurus’? That was very upsetting.”

Gibb’s focus on phonics has been controversial. Many primary teachers have argued that a variety of methods for teaching reading, based on their professional judgment, are more appropriate. His unwillingness to budge on the issue is often characterised by commentators as pig-headedness.

“My role is to initiate a debate

But Gibb’s background gives some clues to a more nuanced approach to education than sometimes comes across.

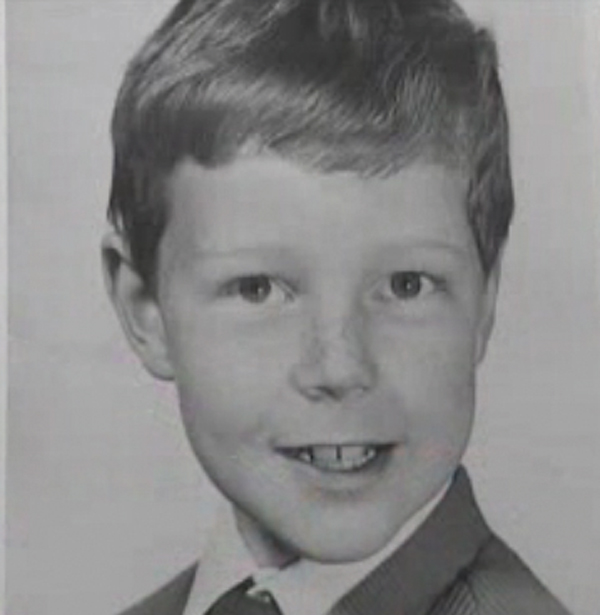

Born in Amersham in 1960 he attended seven different schools as a child, including one in Canada, as the family moved to follow his father’s work as an engineer. His mother, a primary school teacher, took roles in each area, in Canada even turning up one day in Gibb’s own class as the supply teacher. “That was not good,” he muses, “I did not enjoy that day.”

Attending so many schools gave him two advantages: one, an ability to be sociable as he had to keep building friendships, and two, an appreciation for the diversity of schools.

Educated in a grammar school, a comprehensive that had once been a grammar, and a “very weak” comprehensive sixth form, he saw differences in levels of expectation. In the latter he saw a 15-year-old girl reading an Enid Blyton book and “felt shocked”. Not because of the quality of the book, or a snobbery towards Enid Blyton – he is emphatic on this point – but because he feared that her reading ability was of someone much younger.

“She had been let down by the system, by 15 you should be able to read books at a higher level than that.”

He was particularly upset by the inequality in opportunities at the different schools: “I felt they had not had the same advantages as I had up to that point. We should all be able to get the best education that we can possibly get and learn from; in too many parts of the country that isn’t the case – that is why education became such a passion.”

Both his parents were Conservative, although his father kept his political allegiances close to his chest, and Gibb became further involved with the party while studying law at Durham University. Interested in monetarist policies and youth unemployment, he became less enamoured of becoming a barrister and more interested in the economy. During his last year, a careers adviser told him he’d make a good “tax consultant” and so he joined accountancy firm KPMG (then Peat Marwick) where he stayed until his election to parliament in 1997.

It is easy to see how the experience of attending different schools led to his current beliefs that all children should be taught to read fluently and have access to an academic curriculum. A more subtle influence is his accountancy training, which could account for his need to “see things” before he believes they will work. His belief in phonics and a “mastery” model of maths, based on methods used in classrooms in Shanghai, is, he says, because the evidence shows they work.

“I just want children to be taught in the way that they teach in the best environments in the world.

“When you come to the view that one method is far superior and, despite this, there are whole sections of the population being taught with the other method that is significantly less effective, and if you believe passionately in opportunity for every child having a high quality education, then these two things marry and you’ve got to pursue the issue.”

It is an awkward conclusion for a Conservative minister to reach, given that the party has trumpeted autonomy and freedom – particularly in the curriculum – as a major part of its education reforms over the past five years.

Gibb insists he “believes” in autonomy and “allowing professionals to…pause.. grow… pause…as professionals”. He is careful with his words. He explains that instead of telling people what to do he has challenged “prevailing orthodoxies that have been forcing people to take one particular approach”.

It all sounds rather like he is saying that teachers now have the freedom to do what he wants.

“If teachers have better ways of delivering the outcomes then all power to their elbow,” he says.

But what of the maps? The phonics check and the English Baccalaureate are school performance measures brought in to force schools to worry about a specific type of reading and specific parts of the curriculum. Is that really autonomy?

Gibb remains patient, and positive: “Policymakers should have a view about the outcomes they want from the education system, that is the role of politicians”, he says, but he does not think this means being prescriptive.

‘Where I may be different from others in the past is that I do have a view about things like the curriculum, and about how reading should be taught, and how maths should be taught, and I see it as my role to initiate a debate. In the past these issues were often debated beneath the surface amongst educationists in a rarefied atmosphere that never saw the light of day . . . we should all debate this.”

On matters of the manifesto, however, there is no debate. A promise was made that children will know their timestables by age 11, and so the plan is to have a short computerised test at the end of primary school to fulfil this promise. Likewise, the government has promised to judge school performance through progress-based measures, and so assessments for four-year-olds will remain.

Over the hour his views are always coherent, even if you don’t agree with their content. There is though, as opponents always claim, a hint that they are hardened to the point of being impervious.

Gibb disagrees: “If there was a method that said that by teachers standing on their heads they could learn history more effectively I’d want to see it, and once I’d seen it happening and I’d seen these brilliant historians leaving the classrooms, I’d then want to understand the theory behind why this theory was a more effective approach to teaching history than the way I had previously thought.”

His voice gives away an element of incredulity that other methods could be better, but he says, quite emphatically, that if methods different to his own are working he wants to see them – just make sure that you know where it stands on his outcomes map.

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

What is your favourite book?

Any book by Richard Russo – Empire Falls is probably my favourite

A favourite childhood memory?

At the age of 6½, arriving by liner in Montreal, Canada. We emigrated in 1967

If you could live in any period in history what would you choose?

I’m interested in lots of historical periods but would not wish to live in any of them. The present is the best time in human history

Family and pets aside, what item would you save first if your home was on fire?

My spectacles

What job did you want to do as a child?

I wanted to be a barrister

There are several reasons why the child might not be able to read ‘even’ when ‘e’ was covered up. It could be, as Gibb suggests, that she hadn’t been taught phonics and couldn’t sound out ‘v-e-n’. But it could also be she was nervous about reading in front of a stranger. Or that she thought being asked to read a word when part of it was covered up was an impossible thing to do. In any case, v-e-n isn’t a word (unless the girl had been taught about Venn diagrams).

The Enid Blyton anecdote doesn’t necessarily mean the girl’s reading age was low as Gibb feared. It might be because she simply wanted an easy read or that she liked Enid Blyton (I devoured her ‘Adventure’ series, The Castle of Adventure being my favourite). It doesn’t follow that her choice meant the school had ‘let her down’.

Gibb hasn’t ‘initiated’ a debate about such things as phonics (Is it systematic phonics? Or systematic synthetic phonics? Gibb uses the terms as if they mean the same thing but they do not. He is imposing his ideas which he says are backed up by research on to teachers. He says, for example, that the evidence shows systematic synthetic phonics is the best way of teaching children to read. But the evidence he cites actually advocates the systematic teaching of ANY method of phonics. http://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2014/07/nick-gibb-returns-as-schools-minister-time-to-refresh-memories-about-the-evidence-he-uses-to-support-synthetic-phonics/

I would have liked a question on the EBacc and how it has created a hierarchy of subjects and limited access to some subjects.