The majority of free schools opened in areas of need, research has found, but they are usually neither innovative nor opened by parents, and they do not take in enough poor pupils.

The National Foundation for Educational Research, together with the Sutton Trust, have conducted an in-depth analysis of the 311 free schools open as of September 2017, seven years after the coalition government made them its flagship education policy.

Free schools are new schools which, like academies, are outside local authority control and directly funded by the government, and can be set up by groups such as charities, universities, teachers, parents or academy trusts.

Researchers now want a complete rethink of their “mission”, claiming they fail to educate enough poor pupils and have instead simply “become the vehicle for new schools at a time of rising rolls.”

They also want the government to consider streamlining the roles of groups including the New Schools Network, regional schools commissioners, and trusts which currently all help applicants to open new free schools.

Schools Week has the key findings:

1. Most free schools have been set up in areas that need more places

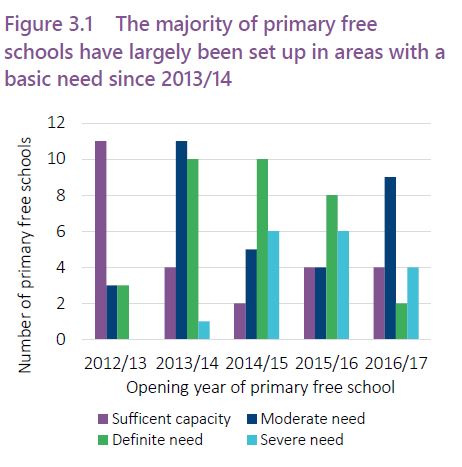

Debate has raged about whether free schools open in areas with a lack of places – gaining heat when the National Audit Office said in 2013 the schools were only patchily helping.

However, researchers find that while the issue may have dogged the early years of the programme, “over time this has shifted, and in later years most new primary free schools have been opened in areas with at least some need”.

Whereas in 2013, a staggering 65 per cent of primary schools were set up in planning areas which already had enough spaces, the next year 84 per cent of primary free schools opened in areas in need.

Over the past four years in total, 85 per cent new primary free schools have opened in an area of some need.

And while no primary free schools opened in areas of “severe need” in 2012, that proportion has since shot up – to a quarter the following year, and 27 per cent and 21 per cent in the years after that. Those opening in areas of moderate and definite need were also relatively high.

Moderate need is where forecast demand for school places is five per cent greater or smaller than the number of places actually available. Definite need is where forecast demand for places is up to 20 per cent greater than the places available, and severe need is where demand is over 20 per cent greater than places available.

The report warns that where primary schools are still opening in areas that have enough spaces, they and nearby schools will struggle financially as they fail to recruit enough pupils.

Secondary free schools have also been set up in areas that need them – but many more are still needed, researchers found.

Recommendation: Given the greater need for secondary school places, regional schools commissioners should “where appropriate use some planned sites for primary schools for secondary school facilities” instead.

Who is responsible for approving new free schools also needs to be clearer. The report suggests that since the Office of the Schools Adjudicator already oversees school admissions, its remit could be extended to oversee new free schools too.

2. Multi-academy trusts, not parents, are opening free schools

One of the intentions of the free school programme was to encourage parents to set up schools in their communities. However, only one in five free schools has had parents involved in their creation – and that proportion has decreased over time.

Parents were involved in setting up about 40 per cent of secondary free schools opened between 2011 and 2013. Of those established since 2015, this has dropped to less than 20 per cent.

For primary and all-through free schools, those opened with parental involvement has dropped from 32 per cent to just four per cent.

Instead, 59 per cent (178) of all free schools have been opened by multi-academy trusts since the free school programme began.

Recommendation: Given that free schools are increasingly set up and led by trusts, rather than parents, and that RSCs are playing a larger role in advising on whether a new free school application should be approved, the government should review the respective roles of the different players in the commissioning process.

This includes reviewing the role of the New Schools Network, “to avoid needless duplication of effort and improve value for public money”.

Mark Lehain (pictured) interim director of the NSN, said his the organisation “very much welcomes the re-focusing [on the role of free schools] and look forward to working with groups who are targeting new schools in [disadvantaged] areas.”

3. Free schools have fewer poor pupils than their catchment areas

Another mission of the free school programme is to provide high-quality schools to poorer pupils, and government ministers frequently claim they achieve this. But both primary and secondary free schools have lower proportions of disadvantaged pupils than their catchment areas.

At primary level, 16 per cent of the pupils in the catchment areas of free schools are eligible for free school meals, but only 13 per cent of pupils attending those schools are eligible.

Similarly, 17 per cent of secondary free school pupils are eligible for free school meals, compared with 19 per cent of pupils in secondary free schools catchment areas.

“These figures suggest that free schools are slightly less representative in terms of disadvantaged pupils compared to the communities that they serve.”

However, free schools are more ethnically diverse than their catchment areas. For primary free schools on average, 61 per cent of their pupils are from an ethnic minority, even though only 51 per cent of their catchment area is. Similarly, in secondary free schools, 47 per cent of their pupils are from ethnic minorities, compared with 45 per cent in the catchment area.

Recommendation: As part of the funding agreements for new free schools, they should be expected to “actively recruit disadvantaged and other under-represented groups of pupils” so they reflect their community.

4. Only about a third of free schools are actually innovative

As new schools created from scratch, free schools are also intended to experiment with innovative approaches to teaching and learning.

However, only a third “were found to have demonstrated such a novel approach.”

Researchers defined innovation as “genuine novelty in the curriculum or ethos”, giving examples such as the Rural Enterprise Academy in Staffordshire, which serves a large farming community and gives pupils access to a working farm, fish hatchery, florist and horse centre.

Another example is the Judith Kerr primary school in south London, where pupils are taught in both English and German, and all staff can speak both languages.

Primary schools are more innovative, with 35 per cent of 152 primary free schools which are still open qualifying as such.

The secondary sector compares more poorly, with just 29 per cent of 113 open secondary free schools counting.

Recommendation: The government must rethink the mission of free schools. They are no longer parent-led, nor often innovative – they are simply new schools now. Free schools need a “clear and distinctive mission”.

5. We still can’t be sure about free schools’ performance

When measuring outcomes, NFER and the Sutton Trust looked at secondary free schools because those set up in 2011 will have had at least one full cohort of pupils spending their entire secondary schooling at them.

Unlike the DfE’s previous analysis, the researchers made sure they matched the key stage 4 pupils in free schools to a control group.

Having done this, they found that free school pupils achieve an Attainment 8 score 1.52 points greater than the pupils in the comparison group, which is equivalent to a grade and a half in one subject.

They also achieve a Progress 8 score 0.12 greater than the comparison, which means a score about one eighth of a grade higher than similar pupils who go to other schools.

The differences are even greater for disadvantaged pupils. Their Attainment 8 score is just over three points higher than disadvantaged pupils in the comparison group, which is equivalent to a higher grade in three subjects. Their Progress 8 score is 0.26, equivalent to a quarter of a grade higher in each subject compared with disadvantaged peers.

Researchers said the “initial evidence appears promising”, but warned the number of free school pupils with key stage 4 outcomes was still too small to be certain about the impact of free schools on attainment.

A spokesperson for the Department for Education said nearly half of free schools which have opened “are in the most deprived areas of the country.

“We are now inviting applications for more free schools and will prioritise those proposals that want to set up in areas with the lowest educational performance and greatest need for more good school places.”

This article reads to me as though a stick that various groups have used to beat Free Schools (because they disagree with the political concept of them) has been taken away so they’ve had to try and scrabble together some more reasons why they can say Free Schools aren’t working.

So a begrudging tick for them opening up in areas which need places. Must’ve been hard to acknowledge that.

But let’s look at who’s actually setting them up. It seems that lessons may have been learnt (strange I know in the DfE) that setting up and running a school is a difficult business (who would have thought). So rather than well-meaning, but in generally quite likely to be naive and inexperienced, groups of parents wouldn’t it be better to have organisations who know how to run schools, and already do so, such as multi-academy trusts? This doesn’t mean parents can’t set up Free Schools, but a higher bar is being set which should mean less failures. Sounds like a positive rather than a negative to me.

How about trying to hit them on their proportion of disadvantaged pupils? Yes, it does seem that the free school intake is not equal to their catchment areas (not that it’s exactly very far off from those figures) but this is hardly likely to be something that the free schools are responsible for. The very worthy recommendation is that free schools should “actively recruit disadvantaged and other under-represented groups of pupils”, as if free schools are actively turning such children away. Most free schools (there are obviously exceptions) are not oversubscribed in the early years and put massive energy into trying to recruit any and all groups of children, with those coming with FSM funding being highly prized.

Someone really scraped the barrel with coming up with the “they’re not innovative enough” stick. Let’s not get into the issue about what on earth would qualify as being “innovative” (neatly avoided above), or indeed that I would think 33% is quite a high proportion if compared to the alternative. If I’m a parent in an area with a desperate need for school places and a new school opens up which is being run well and provides a good education, I’m guessing “well it’s not very innovative” is unlikely to be something I’m complaining about.

And I’m very grateful that so much research was done which ended up with the conclusion that free schools do better, but we can’t be certain about it because of the numbers. Firstly, I’m willing bet that if the outcomes were that free schools did worse we wouldn’t be hearing so much about the uncertainty. Secondly, the researchers knew the numbers involved before starting the research so why go through with it if you’re then going to say that it can’t be relied on?

Finally the astute and insightful statement: Free schools need a “clear and distinctive mission”. What’s wrong with “running a good school”?

Mark – ‘STEM-focused schools, to oracy-based schools, to bilingual schools and schools following alternative curricula’ were descriptions applied to ‘innovative new approaches to schooling’ in the full report (link below) . It’s not always possible to define every word in a short article. Rather than being ‘neatly avoided’, omitting a long description is an attempt to be succinct and keep within a wordcount maximum.

The ones you describe as ‘really scraping the barrel’ because they criticised free schools for not being innovative, are the highly-respected NFER and Sutton Trust. ‘Innovation’ was one of the key selling point for free schools as Cameron made clear in the Telegraph on 13 November 2011: ‘I want them to be the shock troops of innovation in our education system. They are going to smash through complacency.’ It’s fair, then, to judge the programme on whether it delivered on its promise to be innovative.

https://www.suttontrust.com/research-paper/free-schools-analysis-nfer/

Yup, if there’s anything that supports my theory this is it.

We could get to a situation where all free schools are Outstanding, in areas of great need and deprivation, be turning out great pupils, models of good community relations … and people would be saying that that’s all very well but they haven’t delivered on what someone said in an interview with a newspaper in 2011.

Mark – what a cynic you are! The ‘someone’ who wrote an article in 2011 (not interviewed for an article) was David Cameron. It’s true he’s not around any more but he had some importance at one time. But it wasn’t just Cameron. This appeared in the Education white paper, The Importance of Teaching (p73):

‘…our aim should be to create a school system which is more effectively self-improving. The introduction of new providers to the system, and the ability of parents, teachers and others to establish new schools is an important part of this, in bringing innovation and galvanising others to improve…’

Given that this formed the basis of education reforms since 2010, it’s legitimate to ask if these new schools have brought innovation and galvanised others to improve.

Guilty as charged!

But the point still stands. If there is no innovation at all (which isn’t the case) but the free schools are excellent schools and improve the school system doesn’t that mean they’re successful?

It just seems a rather desperate attempt to try to find fault by latching onto a word rather than looking at the bigger picture.

Of course it’s legitimate to question how free schools have performed but education policy and priorities shift over time, so why fixate on a single word included in a White Paper 8 years ago and an article by the former Prime Minister 7 years ago?

Why fixate on a ‘single word’? Because it was a key part of the free school policy and one of the most important reasons given by free school proponents to support their existence.

The ‘bigger picture’ is that some free schools are excellent. Some are not. They’re more likely to be outstanding but also more likely to be less than good. But such comparisons are misleading because there are too few of them.

The ‘bigger picture’ is that free school have ‘largely’ met a need for more school places. But some have not. These threaten the viability of other schools.

The ‘bigger picture’ is that free schools may be in areas of disadvantage but do not necessarily reflect this in their intake.

I have commented on the research here: http://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2018/05/free-schools-have-largely-met-need-for-more-places-but-theyre-not-as-innovative-as-expected-research-shows

What has happened in reality is that the DfE realised there wasn’t enough money to take forwards the free school programme as originally envisaged. So they quietly changed the definition of free school to mean any new school. They also changed the law so that all new schools were expected to be free schools (although technically the VA option still exists). This is the reason why the later free schools have been meeting basic need. Local authorities, which still have the duty to provide sufficient places, have worked with MATs to ensure that applications are submitted for new schools where places are needed and the DfE have largely stopped approving free school applications unless LA stats show the places are needed. These schools are just new schools and I am quite sure that in time we will see that they are no better and no worse than any other schools.

I wonder if the research is based on existing ‘free’ schools, rather than including those which were opened and then closed or even didn’t get to the stage of being opened. This ducks the issue of the amount of money which has been wasted on failed projects at a time when most schools are facing cuts. Another issue, although minor, are those private schools which became state funded ‘free’ schools.