Mike Cladingbowl is an imposing figure with a real “headteacher vibe” – although he’s just six months into his new job. When Knutsford Academy pupils pass him in the corridor there is a sense of awe, and slight trepidation. They are still getting used to their new leader.

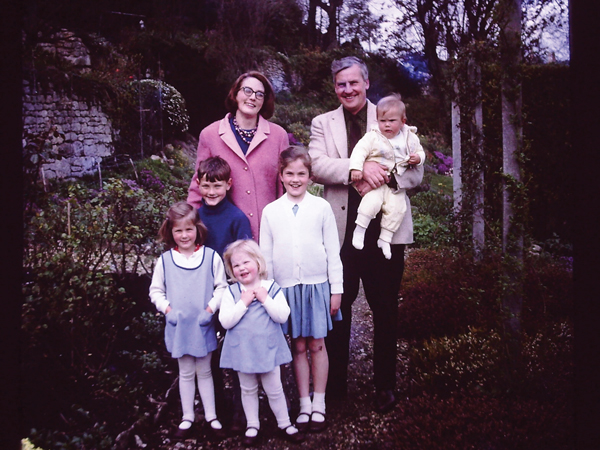

It is most likely his early family life that has created his energetic, restless spirit. His father was in the Navy, so he spent his childhood in half a dozen countries across the world, from Africa to South East Asia.

One of his fondest memories is a family trip to a remote island in Malaya. “We slept on the beach. The sights, the sounds and the smells all stuck with me and helped to make me quite self-reliant. But it was also a different world – we could do anything we wanted.

“I remember one night on this fishing boat, sitting there and flying fish landing on the deck. Fantastic. I don’t know what relevance it has to my life – probably none – but maybe it made me believe you can do different things; that stuff is possible.”

uniforms

The sort of stuff it made possible might include his hitchhike, completed at the age of 15, from England to Gibraltar to see his father.

“It was via Morocco, so you can imagine all the kind of hassle and potential trouble you could get into as a 15-year-old in Morocco!”

He left school at 17, having been bumped up a year at school, with a place to study law at St John’s College, Cambridge. But instead he headed for France’s Cote d’Azur with his older sister and a friend for almost a year. They busked along the coast, Cladingbowl playing guitar, and slept on park benches until they could afford a tent.

“I’ve been bouncing about like Tigger”

A brief spell working – at one point in a galvanising plant – in Germany where he taught English on the side pushed him to “do something”.

He completed a degree at Lancaster in English and German, before a PGCE at the University of Liverpool, then teaching at “tough schools” in the city. His first job was an English teacher at Warrington’s Padgate High School.

But it is for his time in Ofsted that he is most recognised; a journey that began in 2002 when he took up the post as an HMI, after eight years as a deputy then headteacher at Coppenhall High School, Crewe.

In his 12 years at the inspectorate, he worked under three chief inspectors. David Bell – “he wanted to change inspection”, Christine Gilbert – “she wanted to change Ofsted”, and Sir Michael Wilshaw – “he wants to change England”. He became national director for schools under Sir Michael in 2013 before leaving for Knutsford earlier this year.

He has seen the changes in the inspectorate, under different chiefs and governments, and has been a leading force in some of those decisions.

“What government is never very good at, at least in my experience, is the delivery side of things. Anybody can make policy, but making that policy become practice, that’s hard.

“Which is why I think Ofsted is still there, because it suits people to have it there.

“But there has always been a battle, going back 100 years or more, about what Ofsted is there for; is it government tool or independent critic. It’s that tension that makes the relationship tricky.”

He also believes there is some inconsistency in the way that education policy is implemented. He is a fan of autonomy and says he cannot understand why ministers want to dictate “how you should do long division” or whether teachers should use textbooks.

Cladingbowl has strong views on what Ofsted should be doing next – only slipping once and saying “we” rather than “them”.

He doesn’t think the reforms that come in from September go far enough. And he wants to see a fundamental shake-up in the grading system – he says he is tired of seeing “tattered and torn” banners outside schools stating they are outstanding.

“I just don’t think that those places necessarily are, and the difference between outstanding and good for many schools can be . . . well, you couldn’t put a Rizla paper between them; it’s tiny.

“Similarly, I’m not convinced that having two sorts of inadequacy [requires improvement and inadequate] is particularly helpful. It seems to me to be a peculiarly English kind of thing to do that, you know, a delight in nit-picking… and it’s not just peculiarly English, I think it’s a peculiarly English civil servant kind of notion.

“We absolutely should have a system in some shape or another that recognises schools as good enough, but allows some to be identified as not.

“But if they are good enough – and you’re either good enough or you’re not – then you should basically be left alone.”

So, why, at the age of 56, did he give up a top job at Ofsted to run a multi-academy trust in Knutsford?

“I always swore I’d never be an absent dad, and I was in danger of becoming one.” (His children are currently in year 7 and year 4).

“I like new things, and challenges, and a bit of me always likes to be the first to do things. I don’t know of anybody who has ever been senior in the English education system in the way I was in Ofsted, going back to the frontline, just say, ‘I’m going to do it myself now’.

“I have been up and down England, telling thousands of teachers how to do their job, so do you know what? Maybe I should put what I preach into practice.”

His restless spirit is clear. He has a list of things he wants to achieve and he wants to show me everything at Knutsford Academy, the school where we meet. It has been repainted and revamped, ready for September. Pupils’ art hangs on the corridor walls and fresh flowers are placed around the school.

“If all of that sounds a bit obsessive with the physical environment, it is – but deliberately, because it’s emblematic of everything else.”

He truly believes in his pupils and staff (he calls them “extraordinary” more than once). His pupils come from a mixed socio-economic background. “At the roundabout down the road there’s a shop that sells McLaren sports cars, but you can go another 200 yards and find some of the poorest families in Britain.”

At the end of his first six months back in school, and with the summer holidays in sight, he is pleased with his decision to leave Ofsted. “It’s been fantastic! I love it here. I am tired, if I am going to be honest, but I was tired at Ofsted. I’ve been bouncing about like Tigger, driving everybody mad.”

How does he feel about Ofsted coming knocking in the future? (The school is currently rated good). With a cheeky grin, he says: “I’m really looking forward to it!”

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

What was the first album you bought?

Leonard Cohen’s Songs of Love and Hate.

Where are going on holiday next?

France, to visit relatives. After that I hope to take my kids to Greece because I promised Anna when she was at primary school that I would take her to Rome when she was doing the Romans, and to Greece when she was studying the Greeks. You’ve got to keep your promises.

What did you want to be when you grew up?

My mum always wanted me to be a doctor. What I really want to do is play in a bluegrass band.

What is your weekend routine?

On Saturday we potter about and go into the market town and pick up bits and pieces. On Sunday I get up really early and go with my kids to find wildlife. At the moment we go somewhere where there are thousands of rabbits. I’ve got chickens at home – that was an impulsive decision. And a rescue dog. He’s a mad springer spaniel who’d like to eat those chickens if he could. So, part of my weekend is making sure he doesn’t go near the chickens or the rabbits. . .

If you could be one age again for a day, what would it be and why?

I think I would be 17. I was old enough to know there were lots of things I would like to do, but too young to know that I couldn’t do them all. I would have been much bolder and just gone for it.

Your thoughts