For a man in his early 30s, Matt Hood has had a lot of jobs.

But as the inaugural director of the Institute for Teaching chats excitedly from a sofa in his trendy Holborn office building, it quickly becomes apparent exactly how he’s managed to fit so much in.

The same energy and work ethic that once saw him don a bear costume for a few extra quid working at pub chain Brewster’s shines through to this day.

“You used to get paid a bit extra if you were willing to humiliate yourself in the costume,” he admits. “I literally don’t give a shit. I can make anything you want out of balloon animals, I can do face painting, and I’m really good at pass the parcel.”

Balloon animals and Brewster’s bears aside, Hood is deadly serious about his mission.

This week, the IfT begins recruiting its first cohort of 250 “expert teachers”, who will eventually earn their master’s degrees through tailored, small-scale professional development.

The institute is very much Hood’s brainchild. It was in a report, commissioned by the IPPR think-tank, that he last year called foran organisation like it to be established.

But when he first started concocting solutions to the teacher development problem three years ago, while assistant head at Morecambe’s Heysham High School, he never really imagined he’d end up in charge.

It was a conversation with a friend who had just achieved a “black-belt” professional qualification in engineering that first got him thinking.

This friend had been through a learning programme lumbered with “ridiculous” martial arts-related terminology. He was still an engineer – not a manager – but had experienced a “sustained period of clearly structured, accredited professional learning over a period of time”.

“This increased his salary but allowed him to keep doing what he does, which is building things,” says Hood, who identified this lack of a “sequence of learning” as a problem in teaching he hopes to solve.

“I think we spend about a billion pounds a year trying to help teachers to keep getting better,” he says, matter-of-factly. “I don’t think that there is a lot of evidence that that billion pounds is spent very well at the moment.”

One of his issues with “badges” such as “advanced skills teacher” and “lead practitioner” is that the schools community spends a lot of time trying to recognise expertise in the system, but puts “nowhere near as much” work into planning pathways to earn that expertise.

I think we spend about a billion pounds a year trying to help teachers to keep getting better

Following his IPPR report, the eight teaching schools and academy chains that funded the research asked him to set up the very organisation he’d called for.

In a way, it’s hardly surprising that someone with experience of three very distinctive sectors within education has ended up here. At 32, he’s already been a teacher, a teacher educator and a policy wonk at the Department for Education, and he talks with the enthusiasm of someone who’s only just getting started.

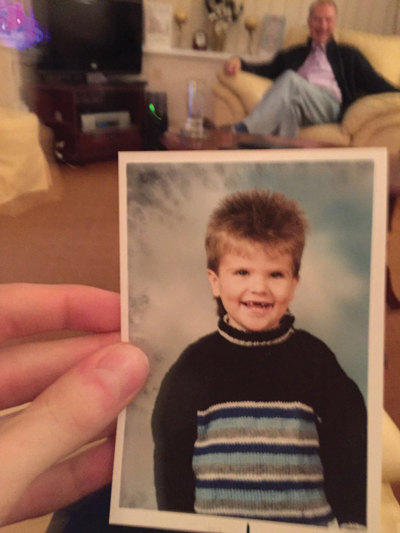

He grew up poor, in Lancashire, part of a “big, complicated, non-nuclear family”. A “decent chunk” of his childhood was spent living in a caravan, but he didn’t know any different and “had a great time”.

His early memories include helping his mum, a teaching assistant, stuff envelopes in their caravan, and sitting the 11-plus at the Lancaster Royal Grammar School. It was on the day of this important test that he observed the “high-stakes” nature of selection, and he has opposed it ever since.

He’ll never forget the boy in tears at the gates, whose mum was “really going at him” about the importance of passing the test.

“My mum, being the wonderful lady that she is, basically just said, as loud as she possibly could within earshot of this other lady, that she did not care at all whether I passed or failed this test as long as I did my best, that’s all that matters,” he recalls.

Nevertheless, he did pass, and as a result, despite the “hilarious complications” of being gay at an old-fashioned boys’ grammar, he got an “incredible education”.

From school he went on to study politics, philosophy and economics at the University of York, which apparently makes him “generally not very qualified but really good at blagging things”.

After graduating, he did Teach First. It was his back-up; he’d applied to the civil service graduate scheme, but he got special permission to defer his Whitehall job for two years.

“I never planned to be a teacher,” he admits. “Then two months later I was in Edmonton in Tottenham, in one of the schools that just doesn’t exist anymore. Like, six per cent at five A* to C, including maths and English. That’s nine children. Those schools just don’t exist anymore.”

Two years later, Hood was in the Department for Children, Schools and Families. He worked on Labour’s efforts to raise the participation age, “which has since happened with no enforcement”. Then the 2010 election happened – and Michael Gove.

He describes it as a “total transformation”, and remembers finding the “munchkins” – the cartoon characters that once adorned the DCSF logo and large parts of its buildings – in a skip in the basement.

Despite his own politics – he describes himself as a “relatively centrist, Hillary Clinton, flag-waving, Labour gay” – Hood is a fan of some of Gove’s reforms. His move to scrap equivalencies in league tables is high on the list.

“All my year 10 kids were doing BTEC business studies, which was worth four GCSEs,” he recalls. “Just bollocks! It’s not worth four GCSEs.”

He points to the English Computer Driving Licence test, “which I actually thought was a driving test for a while”.

“I was like, ‘I don’t even know what this bullshit qualification is’,” he jokes.

In early 2011, he returned to Teach First, this time to set up its north-east office in Newcastle. He was there for less than two years before he moved to the charity Achievement for All as director of policy.

In July 2014, he moved to Heysham as assistant head, tasked with helping the school join a multi-academy trust. The irony of where he had ended up has not escaped him.

“I was the free-school-meals kid who went to the grammar school, and then went on to become an assistant head at the secondary modern down the road, and bash the privileged grammar school at just about every opportunity I could get,” he laughs.

I was the free-school-meals kid who went to the grammar school

But despite having attended a grammar school, gone to a redbrick university, entered teaching through a route designed for elite graduates, and working in the heart of government policy, Hood admits to having felt “totally out of place” for much of his life.

At sixth form, when picked to be part of the UK delegation to the Modern European Parliament, Hood attended events at the prestigious private school Stowe.

“They had fox hunting,” he says, in disbelief. “Like, hounds on the grounds, croquet on the front lawn. I went to supper in a hall that looked like Michelangelo painted the ceiling, you know?”

He got good at pretending to fit in, and “swotting” when he didn’t recognise cultural references. Now he faces a new chapter in his life, and along with it, a new challenge.

He’s back in London, where his teaching career first started. Living with his partner Josh McAlister, also an ex-Teach Firster who now runs the social worker training charity Frontline in King’s Cross, he walks to work in Holborn every day.

There, in modern, open-plan offices which he admits are “far too cool” for a bunch of edu-nerds, Hood leads a team of 30 teacher education curriculum designers. They are testing and refining a five-year curriculum sequence they hope will help create the ultimate “expert teacher”.

They hope to reach 1,000 professionals a year by 2020, and want to become a university in their own right so they can accredit their master’s qualification.

The IfT opened applications for its expert teacher programmes this week, a prospect both “exciting and terrifying” for Hood.

“I’m a teacher from Morecambe, so it’s an interesting change of pace,” he says. “It feels like we’re on the cusp of it being there.”

It’s a personal thing

Your favourite weekend activity

Crossfit. I spend quite a lot of time doing this ridiculous physical activity. I really enjoy doing that on my weekends and then walking, so basically being active.

Your favourite book

I’m a nerd so I’m just a huge Lord of The Rings fan. I think the second is probably my favourite of the three.

Your favourite cuisine

I’m holding myself back because Andy Burnham drives me mad with this answer where all he wants to talk about is how much he likes a certain northern food. They ask, what’s your favourite biscuit? And he says pie. But I am a huge pie fan. In a pub, a good pie.

The job you enjoyed the most

Day to day, teaching I enjoyed the most. I think the second year… the first year was horrendous, it was really hard.

Top holiday destination

Copenhagen. It’s just really cool and fun, and we have a great time every time we go.

Your thoughts